The song Jingle Bells, chestnuts roasting over an open fire, various types of poultry in assorted shrubbery, and horror stories. One of those things doesn’t quite seem to fit with the others, but “scary ghost stories and tales of the glories” have been an integral part of Christmas celebrations for certain cultures for centuries.

But how did something that is now much more associated with the fall and Halloween end up a quintessential (but quickly diminishing) Christmas tradition? Like so many of the things we now celebrate as part of the season, we must look past the symbols used in Christmas celebrations to earlier Pre-Christian times.

Oliver Cromwell may have been hinting about the less-than-Christian origins of some holiday traditions whenever he and the Puritans created an ordinance in 1644—following the outcome of the English Civil War—which abolished the Feast Day of Christmas (as well as Easter and Whitsun, another name for the festival of Pentecost). Shops were to remain open and soldiers would patrol the streets and seize food being prepared for a feast on those days. From 1659 to 1681, the Massachusetts Bay Colony in what would eventually become the United States banned the celebration of Christmas with the penalty being a five shilling fine—approximately three days wages for a skilled tradesman.

Many modern Christmas traditions are a conglomeration of many cultural and spiritual beliefs throughout time; the Yule Log as well as Yule season are often linked to Pre-Christian celebrations of the Solstice in pagan traditions.

The Winter Solstice (also known as hiemal solstice, hibernal solstice, or simply midwinter) is caused by the angle of the Earth’s axis reaching its maximum tilt away from the sun. This event causes the seasons on Earth, with the solstices falling on the points where the axis points directly towards and away from the Sun. In the Southern Hemisphere, this is reversed, with the Winter Solstice falling in June; making surfing at Christmas an appealing thought.

During the Winter Solstice, it was tradition to sit around the fires built to ward off the darkness with the Yule Log and celebrate the rebirth of the sun. Humans haven’t changed much biologically in several thousand years, and a person’s physical reaction to a harmless scare—elevated heart rate, endorphin rushes caused by adrenaline—is still essentially the same. The reaction to hearing a ghost story around the burning Yule fire became a tradition; a feeling of warmth and group bonding at what was the coldest and darkest time of year.

This tradition lasted for several hundred years until Christmas celebrations were halted by the Puritans. Despite many of the traditions making a resurgence during the Restoration (1660-circa 1688), the damage had essentially been done. Along with reducing of the importance of Feast Days during the Enlightenment and Industrial Revolution, many Christmas traditions were now seen as old-fashioned.

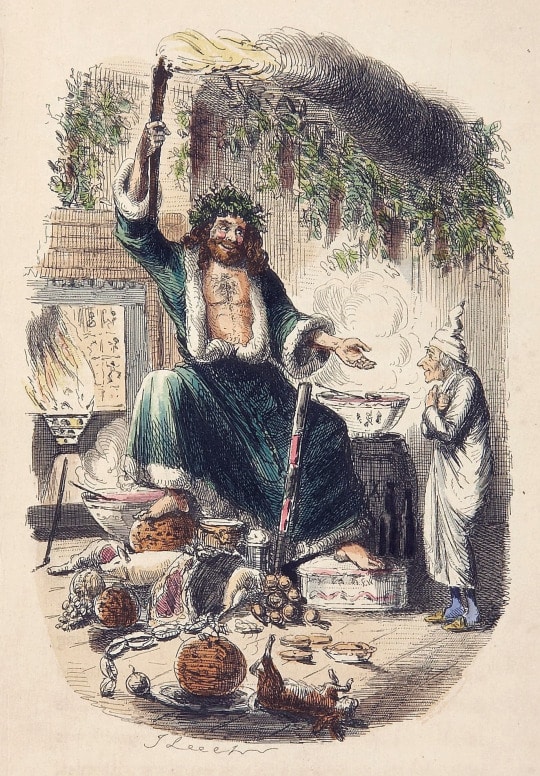

This abruptly changed in 1843 with the publication of Charles Dickens’ A Christmas Carol. While there was a small resurgence of Christmas Spirit taking place as a counter to the dehumanizing aspects of the Industrial Revolution, Charles Dickens was able to capture this burgeoning movement in the text. His story helped reinvigorate Christmas traditions, with a focus on the more humanistic aspects of the holiday—global peace and forgiveness, filial love, and goodwill towards humanity through good works. This caught the Victorian imagination and spawned an entire set of Christmas works by Dickens, including The Chimes, The Cricket on the Hearth, The Battle of Life, and The Haunted Man and the Ghost’s Bargain. Most of these works revisit themes about the crushing effects of capitalism and redemption that are first found in A Christmas Carol (though interestingly enough, never quite approached the commercial success of his first work in the genre).

From there, A Christmas Carol (or, as it may be thought of, a holiday ghost story) has become a cultural phenomenon. “Bah Humbug,” the phrase most often representing Ebenezer Scrooge, has entered the popular lexicon; the figure of Father Christmas helped inspire Thomas Nast during his creation of the modern portrayal of Santa Claus; and the story has been retold in film no less than 27 times since 1901—most importantly immortalized as a cultural touchstone in 1992 by the Muppets.

So this Yule season, relax in the glow of the Yule log, friends, and family and perhaps consider something to send a chill down your spine that isn’t necessarily from the weather. It is one of the oldest traditions after all. And as Dickens reminds us, “let us keep Christmas well.”

Andrew Huntley is a Gallery Experience Presenter in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Pork, Peppermint, and Prosperity

Ask a Scientist: What is the creepiest specimen in the Alcohol House?