by Carla Rosenfeld

The definition of microorganism is any organism that is too small to be seen by the naked eye. They can be single-celled, like bacteria and archaea, or multi-celled, like fungi. Though they are extremely tiny as individuals, these organisms have major impacts on every one of our lives and the environment as a whole. For example, if you’ve ever eaten bread, yogurt, pickles, sauerkraut, or cheese, you have various microbes to thank for the distinctive form or flavor of those foods. But have you ever wondered how we study these tiny organisms out in the field? If they are so small, how do we find them? And once we find them, how do we collect them?

In my research, I try to understand the role microbes play in cycling various elements through the environment. Recently, I’ve been working on a project with a team of people from University of Minnesota School of Earth and Environmental Sciences and Argonne National Lab, to try to understand how microbes influence wetland sediment geochemistry. To do this, a group of us have been trekking around to different riparian wetlands from northern Minnesota to South Carolina.

To get our essential equipment to our field sites, we first pack everything we’ll need into giant coolers, and then seal the sturdy containers. If we’re flying to a distant site, we can ship the coolers to a location near our work site. If we’re driving, we just pack the coolers in a van to haul with us. The coolers are packed to the brim with our field equipment, clothing, gear (including waders and snake-proof boots), and lots of sunscreen and snacks. For work at some sites, we also take a canoe!

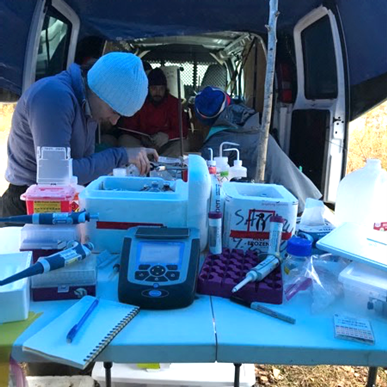

The packed coolers do double duty on our trips, because once we have emptied all our equipment out of them, we can fill them with ice to store the samples collected each day. Upon arrival at the field site, we set up a mobile lab on top of a folding table so that we can process our samples and do any time sensitive analyses. One key component of our mobile lab is a portable glove box, which is essentially a big plastic tent that we fill with nitrogen (yep, you guessed it… we also bring a tank filled with nitrogen gas!). We process our samples inside this tent so that we can cut, scrape, and separate our samples in the absence of oxygen. The controlled atmosphere within the tent is essential because the samples we collect come from underneath the water line, where little to no oxygen is present. Microbes that live below the water line have evolved different metabolic processes that don’t rely on oxygen. So, while we animals are all stuck breathing oxygen, many microbes can use different inorganic molecules like sulfate or nitrate in their respiration. The minerals that form and persist below the water line are also extremely sensitive and may start changing if we expose them to oxygen.

To collect our samples, we use a coring device…which is a fancy term for something that shoves sturdy 7 cm diameter plastic tubes down into the sediment. The tubes are approximately 60 cm-long sections of clear PVC pipe, and we push them as far down as we can. Then we pull up a sediment-filled core that ranges in length from 30-50 cm (that’s about the length of 2-6 bananas placed end to end). Once the core is removed, the clock is ticking for us to separate all our samples out and do our analyses as quickly as possible.

To buy some extra processing time, the first thing we do is dunk our entire sediment-filled PVC tube into a container of liquid nitrogen. The temperature of liquid nitrogen is -90 ˚C… which is cold enough to immediately freeze our samples on contact! We freeze our samples because it slows down or stops essentially all chemical and biological activity and preserves important molecules like DNA (deoxyribonucleic acid) and RNA (ribonucleic acid) that, once collected, can give us clues into what microbes are present in our system. Once our cores are frozen, we transfer them into our oxygen free tent, and remove the full core and separate sections of it based upon depth below the water line, sediment type, or other distinguishing features. We collect some samples to send off to labs for DNA or RNA sequencing. Other samples are collected to bring back to our labs to determine what minerals are present, and for further analysis of other chemical components present in sediment cores.

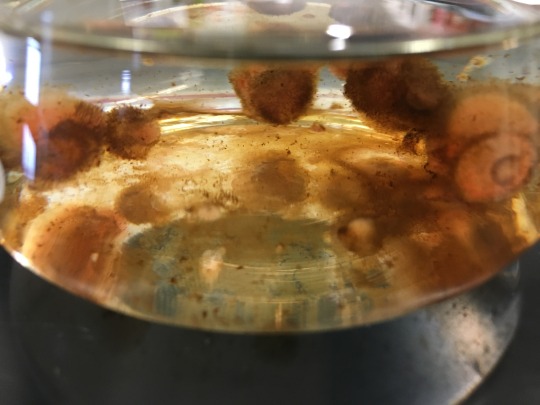

We also collect some cores that we don’t freeze so that we can collect the porewater, the liquid filling all the spaces between sediment grains, and living microbes. The chemistry of the porewater is highly related to sediment microbial activity and geochemistry of the solid sediments. To collect the waters, we stick porous tubes into the sediment cores, and connect those tubes to vials that have a vacuum inside of them, the same mechanical process used when you have your blood drawn at the doctor’s office. To collect living microbes, we take small scoops of sediment and store them in a refrigerator until we get back to the lab and can use the sediment to inoculate microbial growth media. That’s how we eventually add to our microbial culture library, a collection of living microbes with various living strategies and traits that we keep at the museum for research and to lend out to other researchers all over the world.

For a comprehensive understanding of how minerals and microbes vary within the riparian wetland, we repeat procedures of collecting and processing core samples throughout the wetland and at intervals along predetermined lines known as transects, that cross streams and intersect important hydrologic features of the ecosystem. Often, we’ll return to field sites many times over the course of a year or multiple years, so we can better investigate how the microbial activity and geochemical processes change over time with the seasons, as a result of major storm events, or with other environmental factors.

Carla Rosenfeld is Assistant Curator of Earth Sciences at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Fungi Make Minerals and Clean Polluted Water Along the Way

What Do Minerals and Drinking Water Have To Do With Each Other?

Wulfenite and Mimetite: CMNH’s Crystal Banquet

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Rosenfeld, CarlaPublication date: September 22, 2022