New specimens include world’s only juvenile skeleton of plesiosaur Libonectes

Enhancements made possible with support from The Elijah Straw Memorial Fund

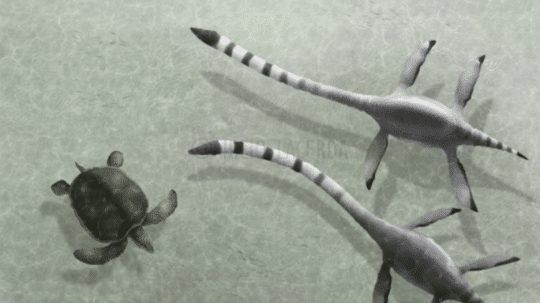

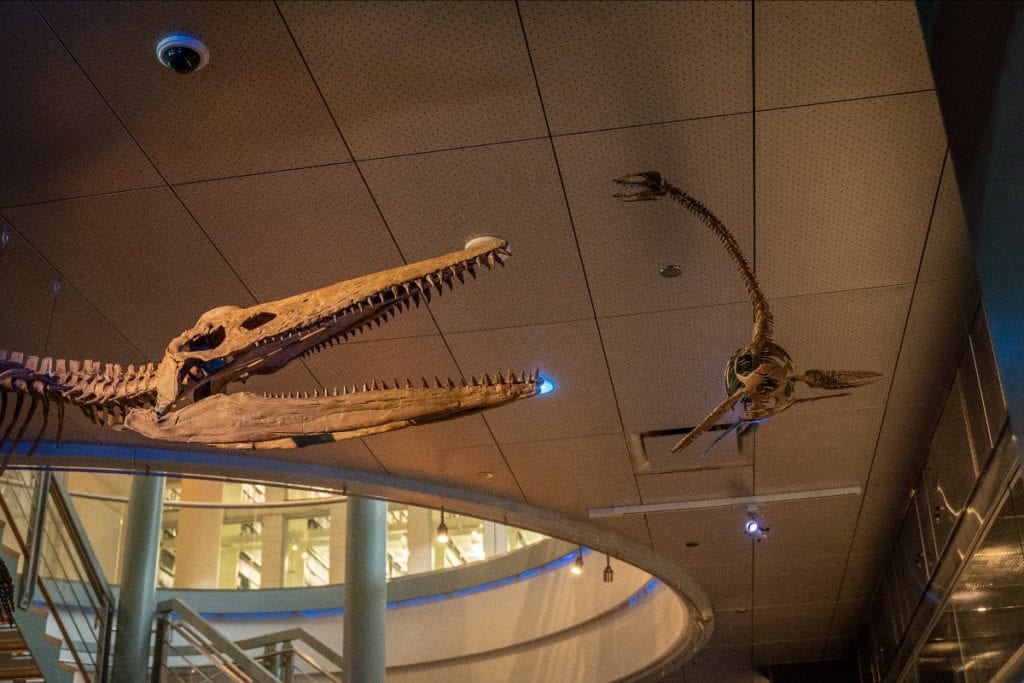

Visitors at Carnegie Museum of Natural History may now view five impressive new specimens in the Cretaceous Seaway display of its flagship exhibition Dinosaurs in Their Time. The specimens include a newly restored Tylosaurus mosasaur fossil skull and four replica skeletons (a pliosaur, a plesiosaur, and two fishes) created by Triebold Paleontology, Inc. The freshly updated gallery is now on view.

“Our new Cretaceous Seaway displays put visitors smack dab in the middle of a life-and-death struggle taking place in midwestern North America some 92 million years ago,” says Matt Lamanna, Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Daniel G. and Carole L. Kamin Co-Interim Director and Mary R. Dawson Associate Curator of Vertebrate Paleontology. “Collectively, our new Seaway beasts tell the story of evolution and extinction in an ancient ocean over the span of more than 30 million years. And they remind us that no species—not even humans—is immune to extinction.”

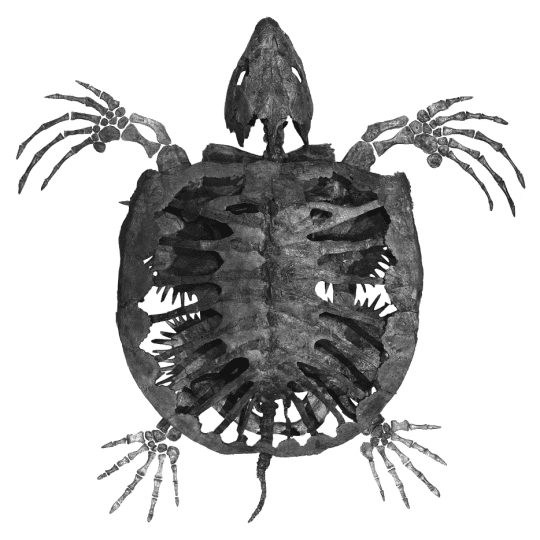

The juvenile plesiosaur Libonectes is the only one of its kind, replica or otherwise, on display anywhere in the world. Lamanna and Triebold Paleontology, Inc. worked closely together to create the specimen. “Nobody’s ever found a baby Libonectes before, so to produce one, the gang at Triebold Paleontology and I had to digitally alter a virtual 3D model of an adult skull and then digitally sculpt other bones using photos of Libonectes skeletons and those of related plesiosaurs,” says Lamanna. “When all the computer work was done, the 3D models were then printed to yield the physical replica. The whole process really opened my eyes to the possibilities of 3D scanning, modeling, and printing in paleontology.”

The new specimens are made possible with support from The Elijah Straw Memorial Fund. According to Tom Straw, Elijah’s father, the natural history museum was a special place for Elijah, and one particular display captured his imagination.

“When Elijah was five years old, he fell in love with the skull cast of Dunkleosteus terrelli, a prehistoric fish,” said Straw. “When that went off view, Elijah was very concerned. I wrote to Dr. Matt Lamanna to ask what was going on,” said Straw, who was surprised when Lamanna responded by inviting them in to see the specimen in the museum’s behind-the-scenes area.

That tour, which also included a glimpse of the world’s first T. rex fossil, led to a lasting friendship with the Carnegie Museums.

When Lamanna learned of Elijah’s death a year later, he put a plan in motion to honor the little boy and his love of prehistoric life. A few months later, he contacted the family to let them know that the museum had dedicated the Dunkleosteus terrelli cast, now back on display in the museum, to Elijah.

The Elijah Straw Memorial Fund has since supported numerous improvements in the Cretaceous Seaway, including lighting, engineering and installation of four new replica skeletons, and the unveiling and display of a real fossil skull of the giant marine reptile Tylosaurus to honor Elijah’s memory. The Tylosaurus fossil skull, collected over a century ago, was newly restored by fossil preparator Dan Pickering, returning the specimen to display after many years stored behind the scenes. Tylosaurus is a member of the mosasaur group, which became famous in recent years for oversized “starring roles” in two Jurassic World movies. The Cretaceous Seaway enhancements were also made possible thanks to the generous support of Dr. Richard W. Moriarty.