Good news everyone: it’s September! We’ve made it to month nine of 12! Sometimes it feels like this year will never end. I take comfort in the idea that if life can survive the traumatic Cretaceous-Paleogene (K-Pg) extinction that killed the non-avian dinosaurs, I can make it through 2020. One of the survival champs of the K-Pg extinction was Champsosaurus, a superficially crocodile-like reptile belonging to the extinct group Choristodera.

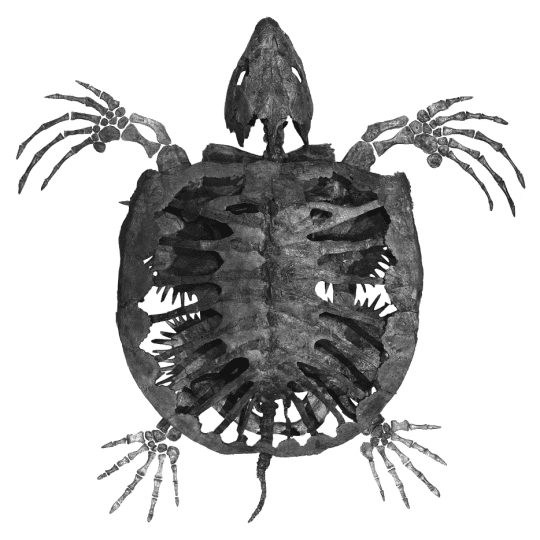

The class Reptilia encompasses an incredible variety of animals: lizards, snakes, turtles, crocodilians, pterosaurs, dinosaurs, and even birds are just a few of its members. In addition to the familiar reptiles that live today, many other reptile groups thrived for millions of years before eventually going extinct. It’s easy to think of dinosaurs like Tyrannosaurus or Triceratops when we talk about extinct reptile groups, but in reality, many extinct groups of animals with no living relatives escape the public eye. Choristodera, an order within the class Reptilia, is one of these groups. Choristoderes were semi-aquatic or aquatic carnivorous reptiles that evolved during the Mesozoic Era (the Age of Dinosaurs) and died out in the Cenozoic Era (the Age of Mammals). Just because they went extinct does not mean they were unsuccessful; the group survived for at least 150 million years! Like many animals, a rapidly shifting environment was probably the source of their demise. Until that point, choristodere evolution was able to ‘keep up’ with the changing times, including the monumental global changes that came with the K-Pg extinction. The combination of a massive asteroid impact in what’s now Mexico, extensive volcanic activity in India, and worldwide climatic shifts resulted in the extinction of over 75% of all species. Research on choristodere teeth suggests that they beat the odds by adapting to new prey.

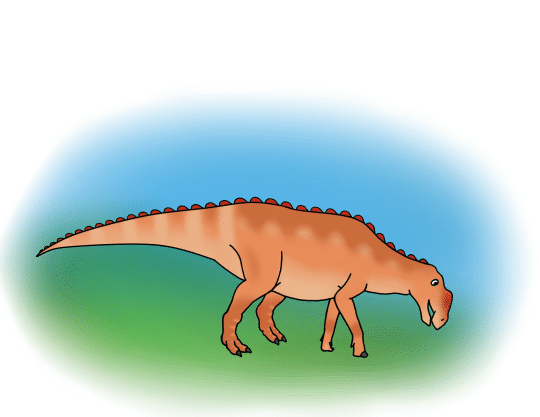

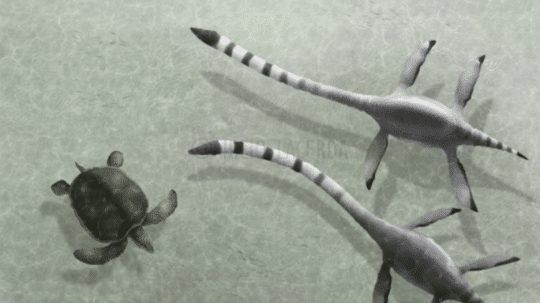

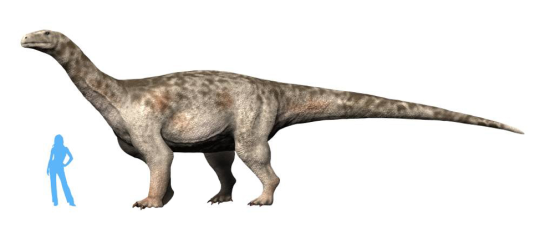

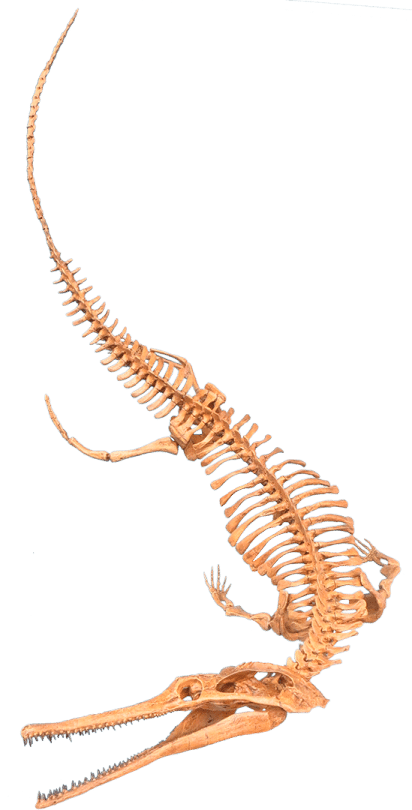

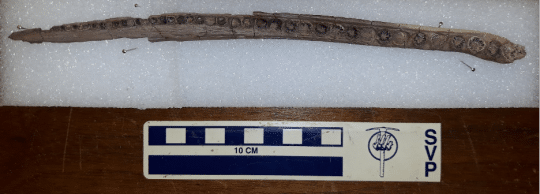

When you think of an aquatic carnivorous reptile, you probably think of a crocodilian – and that’d be right! The crocodilian body plan is a very successful build for hunting prey in the water. As another aquatic carnivorous reptile, Champsosaurus evolved similar traits. This is an example of convergent evolution, in which unrelated species develop similar characteristics to deal with comparable circumstances. (You can read about more examples of convergent evolution in the January edition of Mesozoic Monthly about the sauropodomorph dinosaur Ledumahadi.) Some of the shared features between Champsosaurus and crocodilians include long, muscular jaws for catching fish, eyes at the top of the head for peering out of the water, and a flattened tail that was paddled side-to-side for propulsion. Of course, Champsosaurus and the rest of the choristoderes had many features that set them apart as well. Unlike crocodilians, which have bony armor called osteoderms embedded in their skin, choristoderes just had skin covered with tiny scales. In addition, crocodilians have nostrils on top of their snouts so that they can breathe while lurking beneath the surface of the water; choristodere nostrils were at the end of their snouts, so that they could stick the tip of their nose out of the water like a snorkel and breathe from down below.

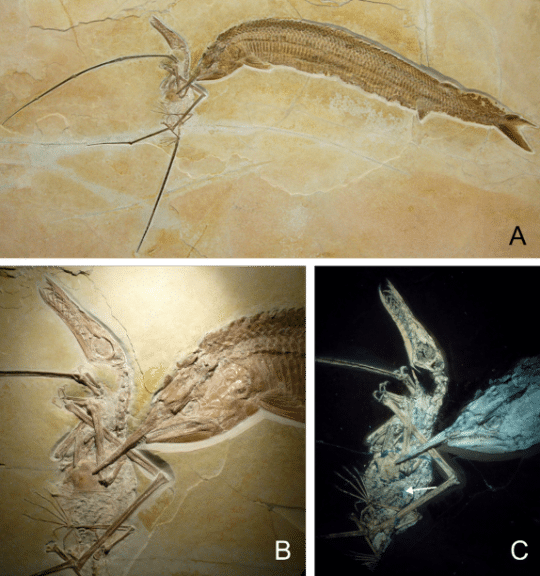

The traits we see in the skeleton of Champsosaurus help paleontologists paint a picture of its behavior. Instead of lurking at the surface of the water, Champsosaurus would wait on the bottom of a shallow lake or stream for prey to come close, lifting the tip of its snout out of the water to breathe. When a tasty fish approached, it would spring off the bottom with its powerful legs and snatch it with its toothy jaws. Despite having strong legs, Champsosaurus was not adapted to a terrestrial lifestyle. In fact, adult males may not have been able to leave the water at all! Fossils attributed to females have more robust hips and hind limbs, allowing them to crawl onto land to lay eggs. According to this hypothesis, the less-robust males would have been restricted to an aquatic-only lifestyle.

Some of the freshwater environments that Champsosaurus inhabited were relatively cold, but that wasn’t a big deal; choristoderes may have been able to regulate their body temperature (a talent known as endothermy or ‘warm-bloodedness’). Crocodilians, by contrast, live in warm, tropical habitats because they are not capable of regulating their body temperature and rely on the sun to warm their bodies (aka ectothermy or ‘cold-bloodedness’). This would explain why choristoderes were able to live further north than crocodilians. However, it seems that crocodilians had the right idea; temperatures around the tropics change less during cooling and warming periods than those at higher latitudes. So, when the current Antarctic ice sheets began to form and the planet started cooling, the temperate choristoderes had to deal with more environmental change than the tropical crocodilians, and finally went extinct. I think the moral of the story is, we would all be handling 2020 better if we lived in the tropics!

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.