by Patrick McShea

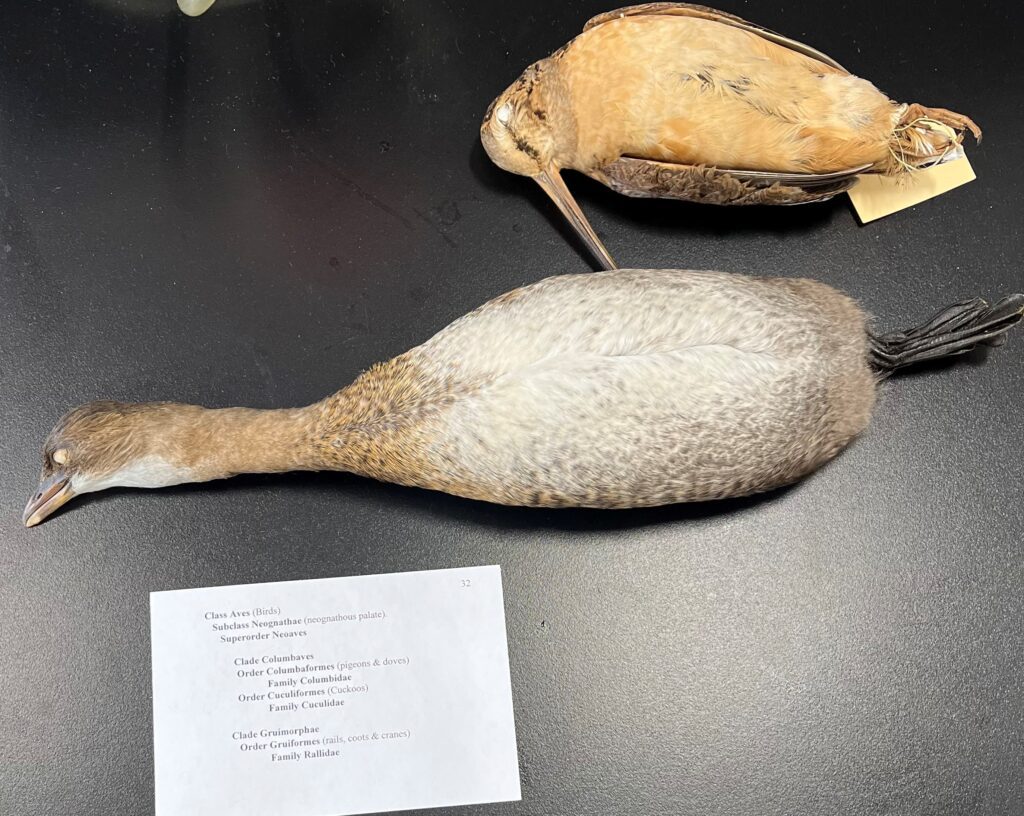

During a recent Vertebrate Diversity Lab at Duquesne University, Dr. Brady Porter’s students closely examined preserved wildlife material on five rows of tables. Weeks earlier, Brady arranged to borrow a variety of vertebrate specimens from Carnegie Museum of Natural History; lizards, snakes, and turtles preserved whole in jars of alcohol, a set of mammal skulls presenting strikingly different dental formulas, and birds preserved in the flat and ridged form known as study skins.

As the manager of the museum’s Educator Loan Collection, I provided 15 bird study skins for the lab. When I expressed curiosity about how the preserved birds would be received by a college audience, Brady invited me to observe the encounter.

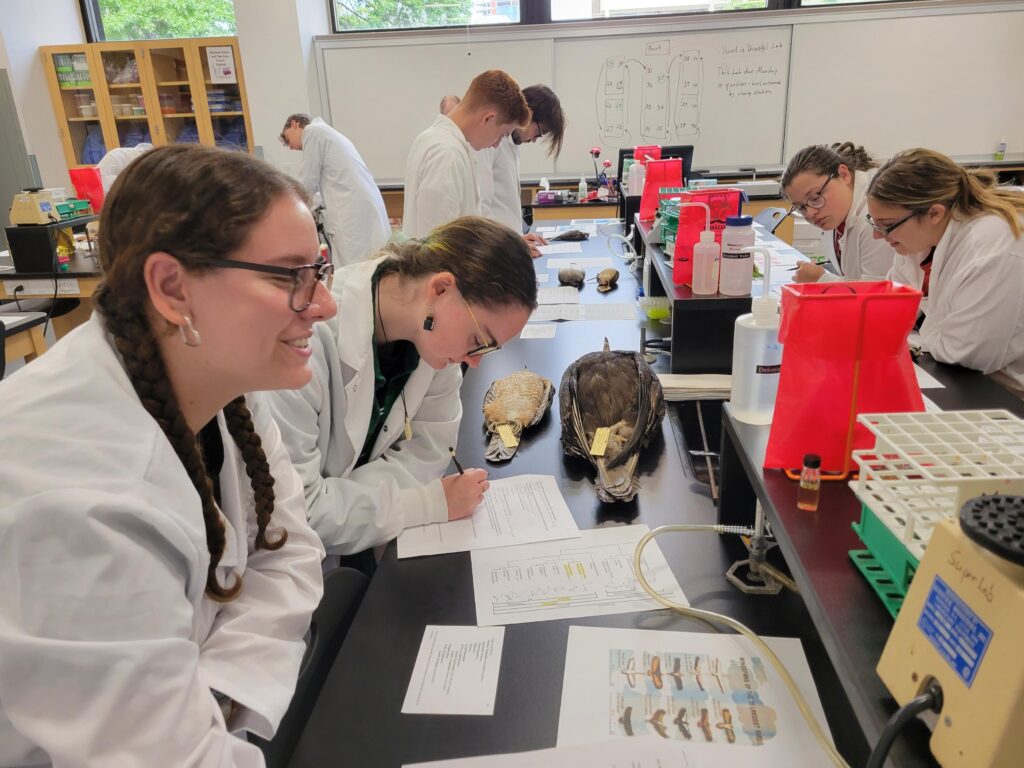

What I observed was an exceptional blend of instruction and inquiry. As the students circulated, singly or in pairs, among the specimen-rich workstations, Brady also moved about the lab, answering individual questions, and providing pointed suggestions in a voice clearly audible to every member of the class. While I watched two students gently check a pied-billed grebe study skin for the presence or absence of the stiff facial feathers known as bristles, for example, I listened to Brady’s advice to a student at an adjoining table who had just picked-up an opossum jaw. “It might be easier to do the dental formula on one side and then double it. And look carefully at every place a tooth could be because teeth can fall out.”

No caveats were necessary for the bird study skins, where worksheet questions directed students to look for and interpret the functional importance of such features as the sharp talons and distinctive hooked beaks of raptors, and the tiny, but fully functional feet of hummingbirds. Some questions served to remind the students about how whole suites of physical features were historically used to create the detailed chart of relationships that is the vertebrate classification system. Here the pied-billed grebe, a species so adapted to aquatic life that mated pairs construct floating nests, provided a tactile reference point for a question directed several levels back in the classification chart. “What is the name of the bird Clade that includes most of the waterbirds?”

During an hour-long observation of the lab, it was clear how much the professor-directed learning experience was dependent upon the authentic materials. Had photographs or digital images been used as substitutes, they would not have conveyed all the information embodied in the preserved birds. In less structured situations, however, the usefulness of study skins as teaching aids fades.

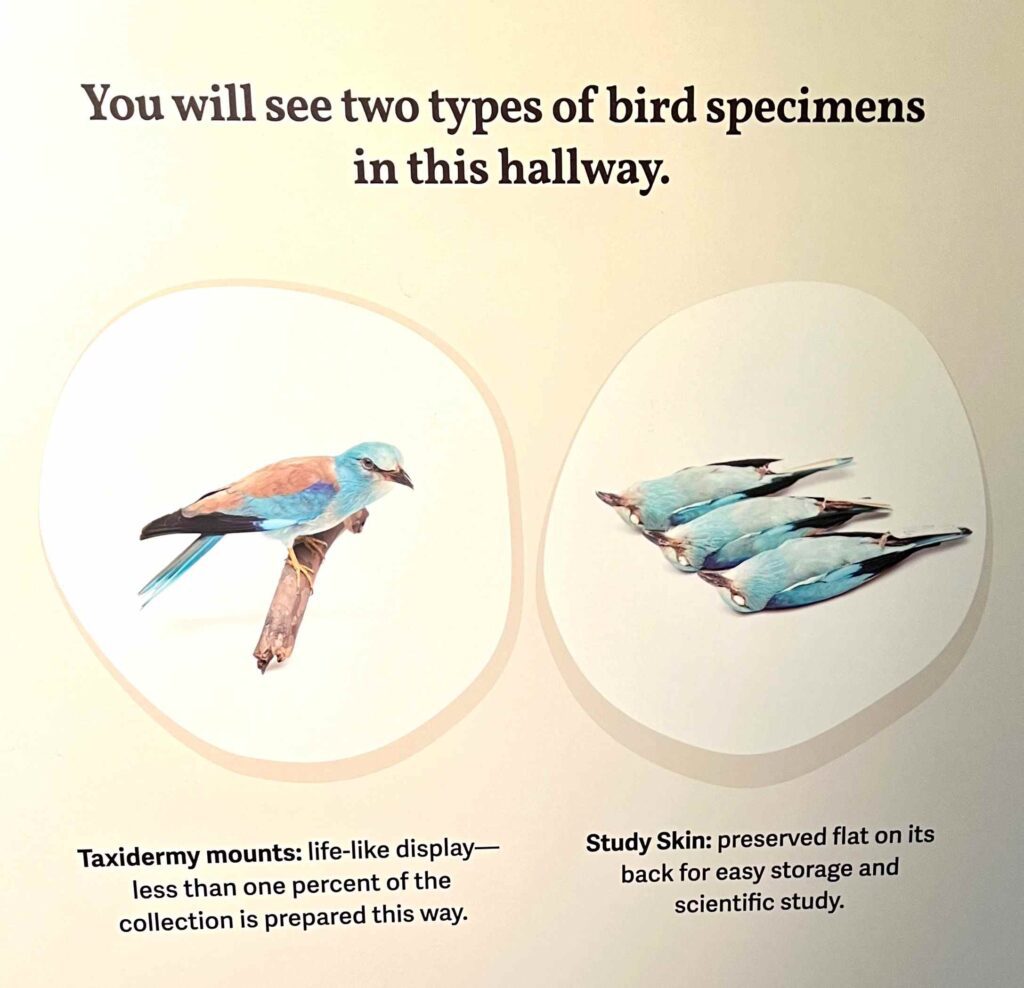

At the museum, visitors encounter 21 study skins displayed amidst nearly 300 life-like taxidermy mounts in Bird Hall.

On the Grand Staircase side of the long narrow exhibition, an informational panel introduces the two types of bird specimens, summarizes their difference, and notes how ratio of preservation forms is completely reversed behind-the-scenes.

In explaining the usefulness of bird study skins to elementary and middle school audiences, I have long relied upon an explanation of theoretic researchers visiting the CMNH Section of Birds to gather data for a study about wing length variation in a species with a wide geographic range. “They’d have a difficult time working with taxidermy mounts.” I’d explain. “One mount might have been prepared with the wings fully open, another with them partially open, and a third with folded wings. With the standardized preparation method and form of study skins, those researchers would get accurate comparable measurements.”

My visit to the Duquesne University biology lab has added a more student-focused detail to the explanation: “Lots of the physical characteristics used for classification can be observed by examining bird study skins, and in a future class you might have an opportunity to be a close observer.”

Patrick McShea is an Educator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Hispanic Heritage Month Scavenger Hunt: Three Birds and a Butterfly

What’s Up With the Dead Birds?

2023 Point Counts at Powdermill Avian Research Center

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: October 19, 2023