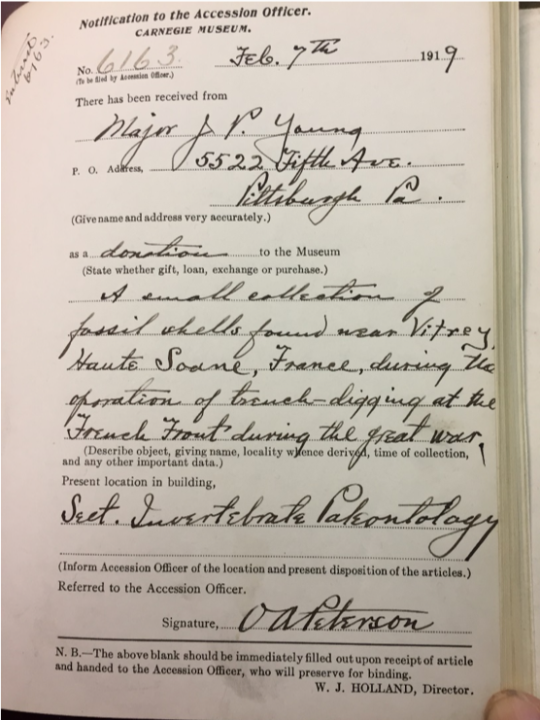

Figure 1: Accession #6163, Donated By Major J.P. Young

What could have inspired someone to arrive at the Carnegie Institute, on a cold winter day to donate a small collection of fossils found while serving in World War I, less than a month after returning to the United States?

Albert D. Kollar, Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, discovered this mystery while undertaking a multi-year project to take a fresh look at the Baron de Bayet Collection, a collection of 130,000 fossils purchased by Andrew Carnegie in 1903. While looking at the trilobites, an extinct group of arthropods, Albert noticed a few specimens missing the characteristic “BH” letters and/or labels that typically identify the Bayet collection. After some detective work, Albert uncovered evidence of a previously unknown collection, “a small collection of fossil shells,” from France, that had been donated by a “Major J.P. Young” in 1919. (Figure 1).

Major Young, born in 1873 in Middletown, Ohio, developed a love of collecting early in life, spotting artifacts from indigenous cultures of North America, while working as a surveyor, for the Pennsylvania Railroad. His connection to Pittsburgh was further strengthened by his marriage to Margaret Young Oliver, daughter of George T. Oliver, industrialist and United States Senator from Pennsylvania. After World War I, John and Margaret settled in Ithaca, New York, where John was affiliated with his alma mater, Cornell University, for the remainder of his life. From 1925-1935, he painstakingly illustrated eight volumes of diatoms, single celled algae with sharp exterior coatings made of silica. Many of these illustrations were published by Dr. Mathew Hohn in 1951. During World War II, John Young volunteered as a “dollar a year man;” so that a Cornell staff member could serve in the war effort. After the war, he returned to his fascination with indigenous artifacts when he reorganized the Seneca and Cayuga collections of the DeWitt Museum in Ithaca, New York. But his longest tenure of service involved the Cornell Paleontological Research Institution (PRI), which he joined in 1934. He served as president from 1941-43 and remained active until his death in 1957. Fellow members of the PRI described him as “scholarly and pleasant” in a memorandum published after his passing.

Which brings us back to those fossils. In 1917, at age 44, John Paul Young joined the United States Army, and was tapped to lead the 5th Trench Mortar Battalion, a unit of 600 soldiers. Sometime between September and November of 1918, while managing his soldiers’ cold, thirst, hunger, and conditions such as “trench foot,” a complication from extreme wetness and cold that could turn a soldier’s foot into a gangrenous mass, Major Young uncovered the trilobite fossils during the excavation of trenches under his command. The construction of a World War I trench is shown in real time in the first 17 minutes of the movie, 1917. After this blog’s original release, Albert watched 1917 on the big screen in January 2020 to gain an appreciation of the difficulty in trench construction shoring the walls with wood, tin, and wire while a battle takes place. To Albert’s amazement the process of digging a 7-foot-deep trench to the top of the parapet out of brown mud and brown colored rock, closely matches the Major’s accession description (Fig. 1) and fossil colors (Fig. 4). The Major noticed fossiliferous rocks at the bottom of a trench along the Western Front in Vitrey-sur-Mance, France (Figure 2). Intrigued to find fossils in a trench, the Major collected and then later donated them to the Carnegie Institute in 1919.

Figure 2: French Locations of Carnegie Trilobites

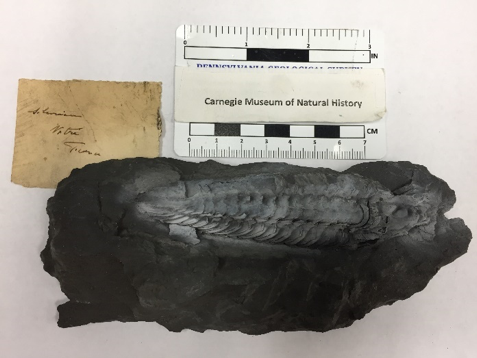

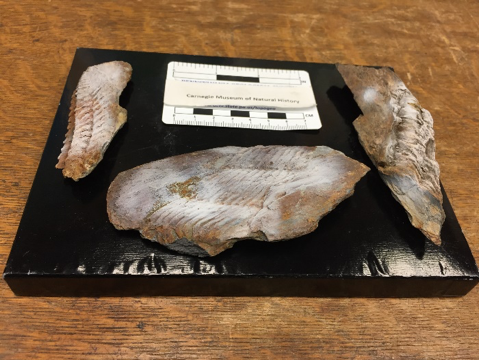

This fall, Albert travelled to Paris to visit the Muséum national d’Histoire naturelle in Paris seeking to uncover this 100-year-old French trilobite mystery. Albert met with Dr. Sylvain Charbonnier, Collections Manager of Invertebrate Paleontology at the Muséum to discuss this puzzle. Albert’s query is to verify the genus, species, age, and stratigraphic locality of these trilobites. At this point, his preliminary research indicates that the Bayet trilobites are distorted and preserved in a black siltstone rock, that Albert recently coated with a white salt to enhance the fossil detail (Figure 3). In contrast, the three trilobites without labels possibly attributed to Major Young (see Figure 4) are also distorted; but preserved in a brown iron color siltstone. The iron oxide coating gives them a reddish appearance. They too are coated with a whitish salt to enhance detail.

Figure 3: Sample of a Bayet Trilobite from Vitré

Figure 4: Trilobites From Major Young Donation

An established paleontological collecting method, crucial to the identification of specimens, is to know the exact placement of the fossil to the stratigraphic locality (rock layer) which can support a known geologic age verified in the Geologic Time Scale. If someone makes a collection, such as the Baron de Bayet, and a paper label is preserved (Figure 3) then, Albert must confirm through paleontology literature and the geologic map of France, all known stratigraphic localities in the region for evidence of similar trilobites. For example, the Vitré label in Figure 3, establishes the location for this trilobite as Bretagne in the northwest of France. To ascertain the proper locality of the Major’s donation (Figure 4), we assume at this point, that it is from Vitrey-sur-Mance in the northeast of France; but further research is planned to resolve the exact location of the of the trenches that the Major occupied in World War I.

Following the advice of Dr. Charbonnier, Albert will proceed to digitize all 50 plus trilobites and send these images and other documentation to the Paris Muséum for further review. While we await the results, the fact that the fossils are sparking a new vein of research is probably exactly what the Major had hoped for all along.

Joann Wilson is the Interpreter for the Department of Education and Volunteer for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology at CMNH and Albert Kollar is the Collections Manager for the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Many thanks to the fabulous Carnegie Library of Pittsburgh staff, with special acknowledgment to Carnegie Museum Library Managers, Xianghua Sun and Marilyn Cocchiola Holt, and Carnegie Reference Librarians Joanne Dunmyre and Leigh Anne Focareta. Special thank you to Peter Corina at the Kroch Library, Division of Rare and Manuscript Collections at Cornell University.