by Deirdre M. Smith

The Society of Animal Artists is an association of international artists who depict nonhuman animals and wildlife scenes in 2-D and 3-D media. Founded in 1960, today there are 500 members living in 25 countries. The Society hosts an annual exhibition called Art and the Animal, and this year’s 63rd edition kicked off at the Stifel Fine Arts Center of the Oglebay Institute in Wheeling, West Virginia. The Society sought nearby artists and scholars to serve as judges and reached out to CMNH. As an art historian whose research often intersects with animal studies (including the question of whether nonhuman animals themselves can be called artists), I jumped at the opportunity to learn more about the Society and see their latest exhibition.

My fellow judges were Larry Barth and Julie Zickefoose, both accomplished animal artists themselves. Larry is an award-winning carver of birds in wood, and Julie paints and writes on birds and other animals, often in watercolor. I was interested to learn that both artists have connections to CMNH. Larry volunteered in the Section of Birds in the mid-1970s, and both artists have sketched study skins from the section’s collection. One of Larry’s impressively-detailed carvings, depicting a Ruffed Grouse, is on display today at Powdermill Nature Reserve.

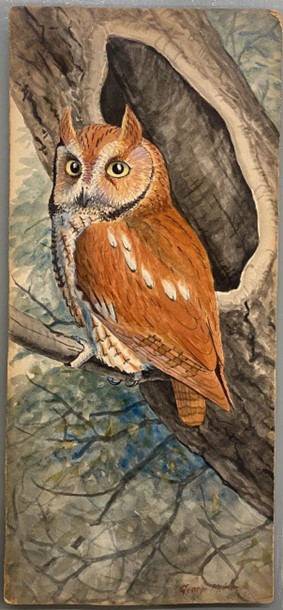

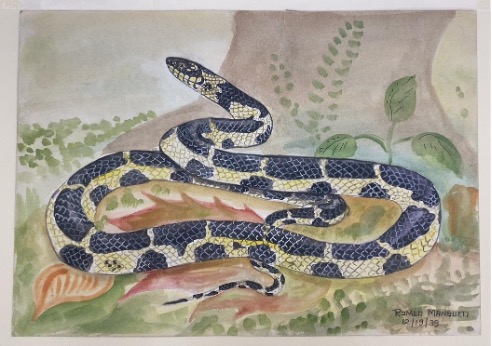

The exhibition featured 116 works by as many artists. Nonhuman animal subjects was the overarching theme, but within that domain artists turned their attention to diverse species: from house cats to cheetahs, dairy cows to zebras, snakes, bears, a southern stingray, and many, many birds: avocets, falcons, herons, owls, penguins, woodcocks, a Eurasian hoopoe, the list goes on. The choices of style and medium were equally varied, from highly detailed, realistic paintings, to decorative cut paper compositions, and from humorous works to ones alluding to the precarious lives of all animals under present environmental crises.

Works from the exhibit: Left, Lisa Nugent’s Follow Me Into the Sea, a depiction of a southern stingray in soft pastels, which was selected for an Award of Excellence. Right, Elke Gröning’s Cozy Cuddling, a colored pencil image of two little red flying-fox bats. Photographs by author.

The judges were tasked with selecting up to eight works that stood out overall for “Awards of Excellence,” as well as four cash prizes. After lunch with Renée Bemis (President), Kim Diment (Vice President), and Wes Siegrist (Executive Director), where the bias against sculptors in the “fine arts” and apple foraging in Appalachia were topics of conversation, we began what ended up being a three-and-and-half-hour-long process of tough deliberations. We were instructed by the leadership of the Society not to let our opinions about a species impact our judgment, and to initially not look at the names of the artists. Otherwise, we were free to use our own best sense as to which works stood out as superlative. As judges we found ourselves balancing assessment of the artist’s technique, choice of medium, the extent to which they had accurately and compellingly captured their animal subject, with the overall visual and conceptual appeal of the work. Some of our most intense conversations and disagreements concerned bird anatomy (something Larry and Julie are expert in), what it means and matters to be “realistic,” and whether artists were bringing fresh perspectives to the genre of animal art.

I felt primed for the task of judging the competition because I had spent the summer with CMNH volunteer Elizabeth Dragus going through each object in the museum’s Natural History Art collection, which features hundreds of naturalist illustrations made by artists, scientists, and several former CMNH staff between the nineteenth and twentieth centuries. Established in the early 1970s as the M. Graham Netting Animal Portraiture Collection, it is a treasure trove of images and sculptures of birds, fish, insects, mammals, and reptiles. Several artists in the collection are members of the Society.

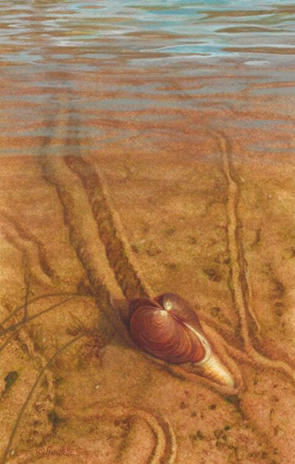

One work that received much commentary from the judges, and eventually an Award of Excellence, was Rachelle Siegrist’s Nature’s Incredible Water Filter, a petite (6 x 4 in.) charmer of a watercolor painting depicting a freshwater mussel leaving a trail in sand. The only bivalve subject in the whole show, the work equally stood out for the way the artist captured the patterns on the surface of the water above the mussel. In the statement that accompanies the image in the exhibition catalog, Siegrist shares details on the lives of freshwater mussels: their ability to filter bacteria and pollutants, their role as an “indicator species,” and the rising threat of extinction that these organisms face.

Animals of other species are the most enduring subjects of human image-making, stretching back to the oldest surviving image in a cave, the “Sulawesi pig.” Humans have made images of other animals in order to worship, marvel at, allegorize, objectify, and study them. Siegrist’s little painting demonstrates the power that this primordial practice of taking the time and effort to make an image of another animal can hold: she offers the viewer the opportunity to pause and contemplate a little being whose life might otherwise go unnoticed, or be inaccessible, and develop a new relationship to it through her act of representation.

Deirdre M. Smith is an Assistant Curator at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Smith, Deirdre M.Publication date: November 21, 2023