Perhaps on a past visit to the museum you have noticed the large, heavy wooden doors and wondered what lay beyond. You might have seen staff members using these doors to access the mysterious spaces beyond and wondered what they do. Maybe when you think of the museum, you think in terms of its ‘collections,’ which are vast—specimens, artifacts, dinosaur bones, gems, and more. Indeed, many of the museum staff do manage the collections, tirelessly cataloguing, preparing, and preserving our Natural History.

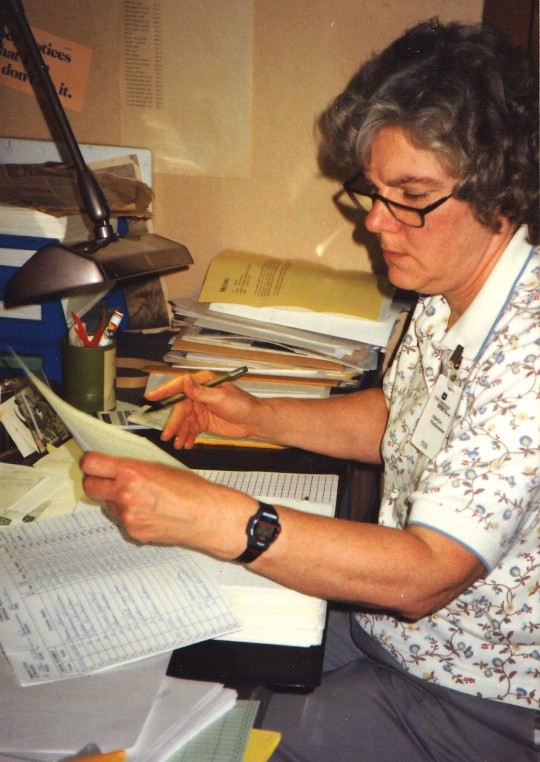

This past January, we had the opportunity to celebrate the work of Marilyn Niedermeier who was employed at the museum for almost 43 years! In a quiet corner of the third floor, behind a door labeled “Section of Birds,” Marilyn spent her career caring for a collection of data.

Since 2007, Marilyn was the person in charge of data gathered at the Bird Banding Lab at Powdermill Nature Reserve, the Carnegie Museum’s scientific research station in the Laurel Highlands, about an hour (58 miles) southeast of Oakland.

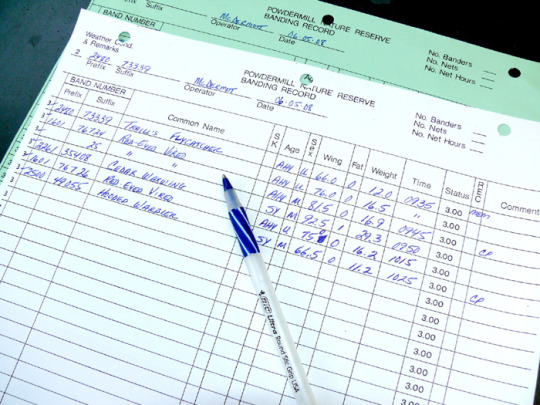

Started in 1961, the Powdermill Avian Research Center bands about 10,000 birds per year and processes another 3-4,000 recaptured birds (already banded). Marilyn’s job was to organize, proof, catalogue and submit those data to the National Banding Lab. How did she do all that from 58 miles away, and what does that collection of data look like?

In the early days, long before the invention of desktop computers, Powdermill data were handwritten on paper data sheets which were hand-delivered to the museum up until 2010! Although they rarely met face-to-face, Bob Leberman (founder of the banding program) and Marilyn frequently exchanged hand-written letters to resolve discrepancies in the data. Reports to the banding lab were prepared on a typewriter and snail-mailed to Maryland.

Over the years, as the database grew bird by bird, Marilyn witnessed many changes in the way the data was handled, from the antiquated computer punch cards (so advanced for the time) to the evolving world of desktop computing. As the binders filled up with datasheets, Marilyn navigated through several iterations of software needed to maintain the growing database and soon hand-written letters were replaced by email and eventually the data sheets were replaced by a direct-entry program at the Powdermill banding lab. Even with direct-entry of data, it doesn’t end there. The data must still be checked for accuracy and consistency and then submitted to the national lab.

For the over two decades, Marilyn worked tirelessly, with a ready smile, under a sign above her desk that read “No one notices what I do until I don’t do it!” Through her efforts and that of the scientists at Powdermill who faithfully collect the data each banding day, the dataset of the Powdermill Avian Research Center is one of the largest and most accurate in the country. Marilyn, we wanted to say, “We noticed,” and we couldn’t have done it without you!

Mary Shidel is a Field Assistant at Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Powdermill Nature Reserve. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.