by Patrick McShea

In the final hour of a Saturday-long visit to the museum by a Kent State University class, a student who played high school basketball volunteered to read aloud to nine college classmates. “With that experience you’ll do a great job,” I explained as I handed her a paper bearing a single long paragraph, and then directed her toward a quiet corner of the exhibit hall to a practice the assignment.

While the majority of the 40-student class opted to spend the unscheduled block of time exploring the exhibits and visiting the museum shop, ten students had accepted my offer to guide them on a tour of the Alcoa Foundation Hall of American Indians.

The now 23-year-old exhibition is divided into quadrants with a different culture presented as a focal point in each, the Tlingit of the Northwest Coast, the Hopi of the Southwest, the Iroquois Nations of the Northeast, and the Lakota and their neighbors of the Great Plains. The twin themes of Native diversity and the continued vibrancy of Native cultures are repeatedly addressed in the hall’s displays. When I paused the group at the Lakota Winter Count display, and recruited the volunteer reader, I hoped to delve a little deeper into both themes.

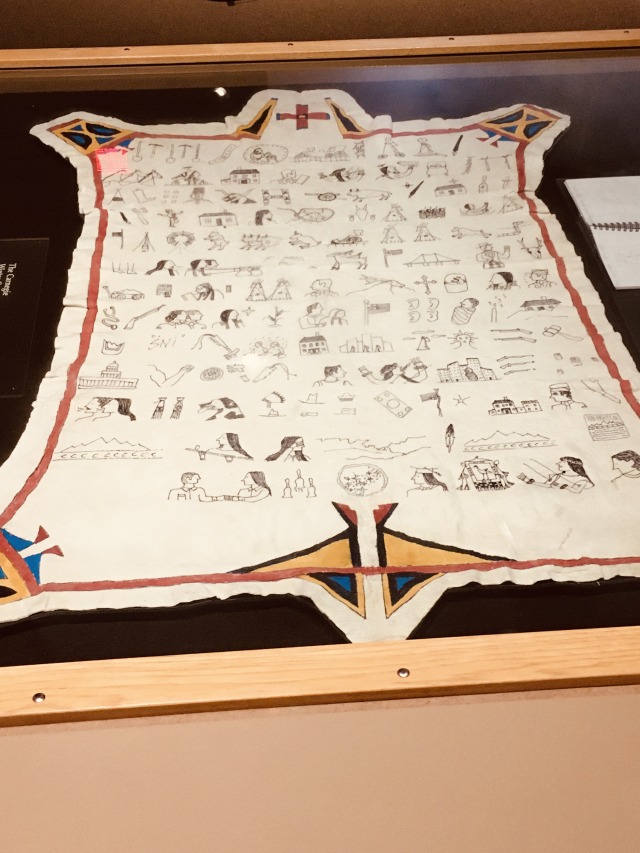

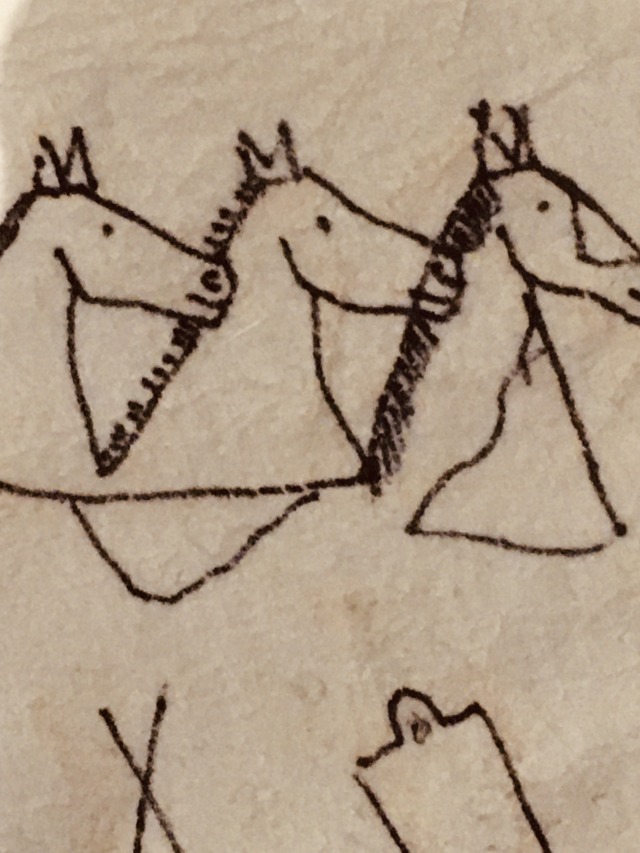

Winter counts are a method by which groups of Lakota People record and remember their history through pictographs on a tanned animal hide or sturdy cloth. Each year, after leaders review important events and agree upon the previous year’s most significant occurrence, a new entry is added to the unique document. A designated count keeper holds the responsibility to annually recite, in sequence, the story behind each pictograph, and thereby orally pass along the group’s history to a listening audience.

The Winter Count on display, which covers a period of 125 years for the Sicangu Lakota people on the Rosebud Reservation in South Dakota, was created specifically for the exhibit by Dr. Thomas Red Owl Haukaas (Lakota/Creole). After summarizing the importance of winter counts for the students, I read aloud the artist’s explanation of his work from a nearby label: “My winter count is from a contemporary viewpoint. It purposely includes community and national events, men and women, fullbloods, and mixedbloods as an attempt to capture the richness and complexity of our tribe.”

The mention of contemporary viewpoint provided the opportunity to introduce another, albeit non-Native one, author Ian Frazier’s description of high school basketball star SuAnne Big Crow in On the Rez, his 2001 account of life on the Pine Ridge American Indian Reservation.

I called back the volunteer reader and provided background for the description of an event that might be judged worthy of winter count commemoration. “The quote you’re about to hear is pulled from a considerably longer story. It describes how in 1988, SuAnne Big Crow, who was then a 14-year-old basketball player from the Pine Ridge Reservation, transformed the racially charged playoff game atmosphere during pre-game warm-ups at a school in Lead, South Dakota, a white town located outside the reservation. Her actions were brave, clever, defiant, desperate, and heroic – all at the same time.”

As someone who experienced the intimidating atmosphere of away basketball games, the volunteer brought an authentic voice to her task, confidently reading Frazier’s account of SuAnne dribbling as she led her team onto the court of the “deafeningly loud” high school gym. Her voice shifted to a slightly higher register, however, when the narrative departed from normal pre-game procedure.

Then she stepped into the jump-ball circle at center court, in front of the Lead fans. She unbuttoned her warm-up jacket, took it off, draped it over her shoulders, and began to do the Lakota shawl dance. SuAnne knew all the traditional dances – she had competed in many powwows as a little girl – and the dance she chose is a young woman’s dance, graceful and modest and show-offy all at the same time.

The reader’s calmer voice returned where the account quoted the impressions of SuAnne’s surprised teammates, then turned higher as the action continued.

SuAnne began to sing in Lakota, swaying back and forth in the jump-ball circle, doing the shawl dance, using her warm-up jacket for a shawl. The crowd went completely silent. ‘All that stuff the Lead fans were yelling – it was like she reversed it somehow,’ a teammate said. In the sudden quiet, all you could hear was her Lakota song. SuAnne stood up, dropped her jacket, took the ball from Doni De Cory, and ran a lap around the court dribbling expertly and fast. The fans began to cheer and applaud. She sprinted to the basket, went up in the air, and laid the ball through the hoop, with the fans cheering loudly now. Of course, Pine Ridge went on to win the game.

The reader earned a sincere round of applause from her classmates for her efforts. I, in turn, felt a rewarding sense of accomplishment when she asked to keep the now deeply creased paper in her hands.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Museum Conservation: Cleaning the Kayak in Wyckoff Hall

Winter Wanderers on a Water Tower

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: McShea, PatrickPublication date: March 18, 2021