Mollusk shells persist long after the death of the soft-bodied animals whose secretions formed the protective covers. These sturdy remains can inform us about species living in an area at that time. Many mollusks occur in specific habitats and during certain time periods in Earth’s history. When we find mollusks in sediment with dinosaur bones, for example, we receive a clue about the geologic age and habitat in which those dinosaurs lived. When mollusks first appear in an area, deposits containing their shells allow us to estimate when events in Earth’s history occurred, including archaeological events, or even relatively recent construction projects.

This morning as I walked across the Panther Hollow bridge near Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, I noticed clam shells in the concrete of the sidewalk. What can the presence of these clam shells tell me about how long that sidewalk has been there?

Concrete is a mixture of cement with sand and gravel. When sand and gravel are taken from rivers, this natural resource sometimes contains clam shells. I believe the clam shells in this sidewalk were scooped up along with the sand and gravel to make the concrete. Then after the sidewalk was poured, but before it fully hardened, the clam shells floated to the upper surface.

As an aside, information about comparative densities is instructive here. Two common crystal forms of calcium carbonate are calcite and aragonite, which have different densities (calcite 2.71g/cc, aragonite 2.93). Most mollusks form shells of aragonite. However, shells are not pure aragonite, containing small amounts of protein and other substances, so clam shells can have densities around 2.5-2.6. In comparison, the density of quartz, which makes up much of the sand used in making concrete, is 2.65. The clam shells are slightly lighter than the sand, which probably explains why they floated up to the sidewalk surface.

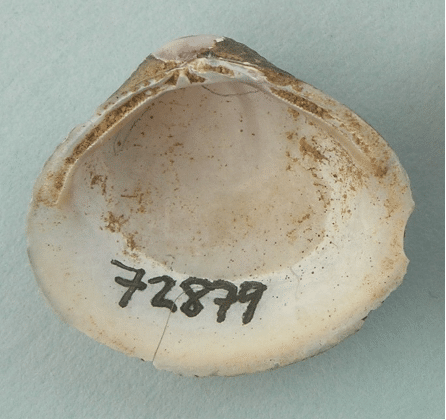

I identified these clam shells as Corbicula fluminea (common name: the Asian clam). They have the characteristic shape and size, the outside has strong regular growth ribs, and on the inside, the lateral teeth bear minute serrations. This species was first recorded in North America in British Columbia about 1924. As an invasive species, it has spread, through human activity, to at least 46 US States.

When did the species appear in southwestern Pennsylvania? There is a record of Corbicula fluminea in 1979 from the Ohio River just downstream from Pittsburgh and another in Greene County, southwestern Pennsylvania from 1981. Museum records of this species became more common after about 1993, suggesting that the clam probably became more common about then.

Consequently, I conclude that the Corbicula fluminea-containing concrete sidewalk on the bridge next to Carnegie Museum must have been poured after the late 1970s, and possibly after 1993, when the clam became abundant in freshwater of western Pennsylvania, the region where Pittsburgh is located.

Museum collections provide useful information about when non-native species arrived in an area. Now you know that one of the many uses of mollusks is estimating ages of things.

Although some people might think of clams as an abstract concept, here is an example of clams in the concrete!

Timothy A. Pearce, PhD, is the head of the mollusks section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is the biggest snail?