Honeysuckles will be back soon.

But this one never really left for the winter.

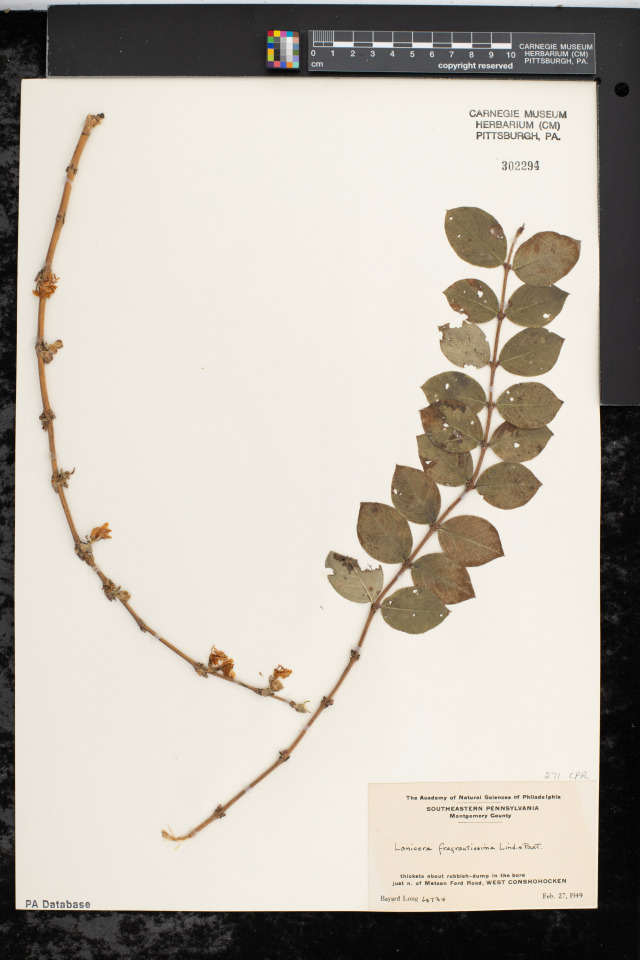

This specimen of winter honeysuckle (Lonicera fragrantissima) was collected in West Conshohocken, PA near the Schuylkill River outside of Philadelphia by Bayard Long. Collected flowering in a “rubbish-dump,” no less! Bayard Long (1885-1969) was a Philadelphia-area botanist and an active member of the Philadelphia Botanical Club (founded in 1891 and still exists today). He was a prolific collector and served as Curator of the Club’s Local Herbarium for 56 years (housed at the Academy of Natural Sciences). About 982 specimens collected by Long are preserved for the long haul in the Carnegie Museum herbarium.

Winter honeysuckle not only has a fun scientific name to say (“fragrantissima” rolls off the tongue) but is easy to identify among the many species in the honeysuckle genus (Lonicera in plant family Caprifoliaceae). That is, it has almost evergreen, thick leaves that partly persist into the winter, unlike any of the other shrub honeysuckles in Pennsylvania. (Emphasis on shrub, because the invasive vine Japanese honeysuckle – Lonicera japonica– also has persistent leaves through much or all of winter).

It is also known as “sweet breath of spring” for its aromatic flowers (hence its specific epithet, fragrantissima – think Bath and Body Works scent), which appear in late winter (and in this specimen!).

Introduced from China as an ornamental and often planted for its foliage, this species is now invasive in many states in the US. I must admit I don’t see it very often “escaped” outside of plantings in Western PA, but that doesn’t mean it doesn’t exist, or won’t escape in time, especially given it is problematic in other areas of the US.

So, you really shouldn’t plant it. Though Pennsylvania has native honeysuckles, the most abundant and common ones are introduced, affecting native vegetation and wildlife.

Find this specimen (and search for more) here.

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They are in the midst of a project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: How do you find rare plants?

Do Plants Have Lips? No, But One Genus Sure Looks Like it Does!