Archiving biological variation.

by Mason Heberling

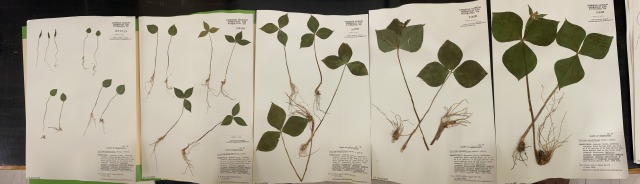

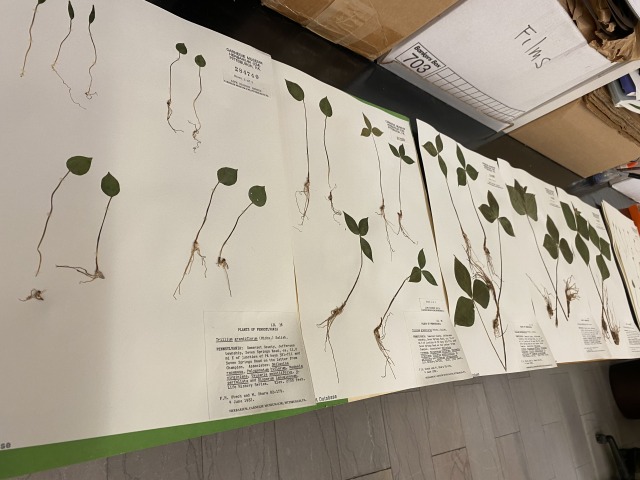

This specimen is not a specimen but a set of five specimens! Same species (large flowered trillium, Trillium grandiflorum). Same site (in Somerset county, PA). All collected on same date (June 4, 1982) by Frederick H. Utech and Masashi Ohara.

We know that one specimen of every species is not enough. Having many specimens of many species, across many sites, and through time are necessary to document what organisms lived where, when, how far species ranges extend, and how these change through time. We study these specimens to understand biodiversity and biodiversity change across many scales.

But why collect that many vouchers of the same species, from the same site, on same date? One reason might be to send “duplicate” vouchers to other herbaria, both to help other collections expand their holdings, to get expert opinions on identification, and/or to protect against (unlikely but very possible) damage that may happen in one herbarium (like fire, flood, insect damage – oh my!).

But that isn’t what happened here. All specimens are stored together at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

So why? Well, it is simple, but quite genius, really. Utech and Ohara collected a “life history” voucher series. That is, these specimens each show different stages of the species’ development from small cotyledon-bearing seedlings just germinating above ground, to one leaved plants, to small to large three leaved juvenile trilliums that have not yet flowered, to large adult plants with flowers.

Utech and Ohara, along with Shoichi Kawano, pioneered this method of collecting and advocated for its importance in a 1984 essay in the Journal of Phytogeography and Taxonomy. Historically, plant specimens are collected with a major specific purpose in mind – to document the plant was there at a given time. To do that, botanists of course collect specimens that are best for identification, such that others can verify the species. For most species, that means plants tend to be collected when they are adults and reproductive (with flowers and/or fruits). Specimens without reproductive organs (called “vegetative” specimens) are generally viewed as less useful for this purpose and often avoided.

But Utech and others found that this standard approach, though useful for some research, did not cut it for their work. As organismal biologists studying the life history, ecology, and life cycle of species, they found many species were not well represented in herbarium collections.

Many species, like trillium, have distinct life stages from seedling to juvenile to adult. Many species form overwintering leaves or juvenile leaves that differ dramatically, even unrecognizably, from “typical” adult specimens.

So there’s good reasons to collect across life history and across individuals within a population. Biological collections are all about archiving biodiversity in its many forms, whether across deep time with fossils, across species, within species, or even within populations at a specific site.

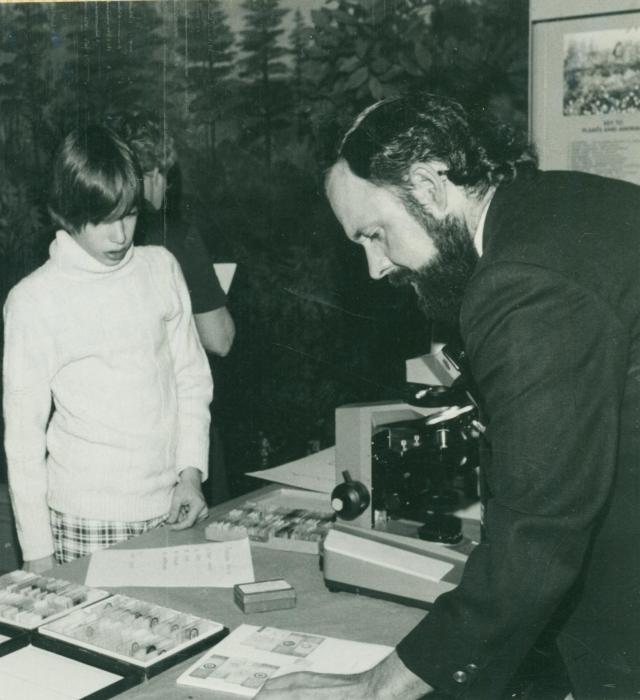

Dr. Utech (1943-2021) was a curator at the museum from 1976 until 1999. He was then a research botanist at the nearby Hunt Institute for Botanical Documentation until his retirement in 2011, notably contributing to three volumes of the Flora of North America project. More than 23 thousand specimens in the Carnegie Museum herbarium were collected by him. Dr. Utech passed away earlier this year but his legacy lives on. You can find his obituary here.

Inspired by the method of life history series and the need for new perspectives in the way we collect, CMNH Botany staff are working to promote and expand these ideas. We are presenting some of these ideas at the Society of Herbarium Curators annual meeting later this summer.

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They are in the midst of a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Collected On This Day: September 6

Ask a Scientist: How do you find rare plants?

Do Plants Have Lips? No, But One Genus Sure Looks Like it Does!

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Heberling, MasonPublication date: June 4, 2021