by Mason Heberling

You can get see plants from all over the world without ever leaving the herbarium. Herbaria are powerful resources that enable research that would otherwise not be possible, comparing plant species collected from across the world, at different times of year.

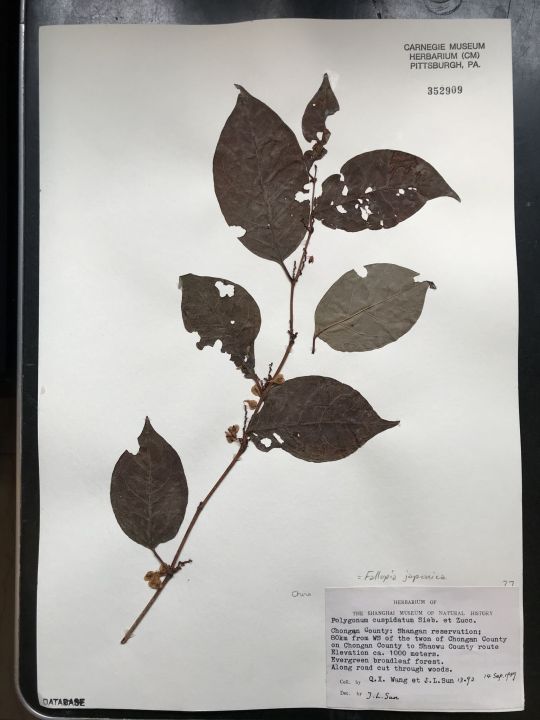

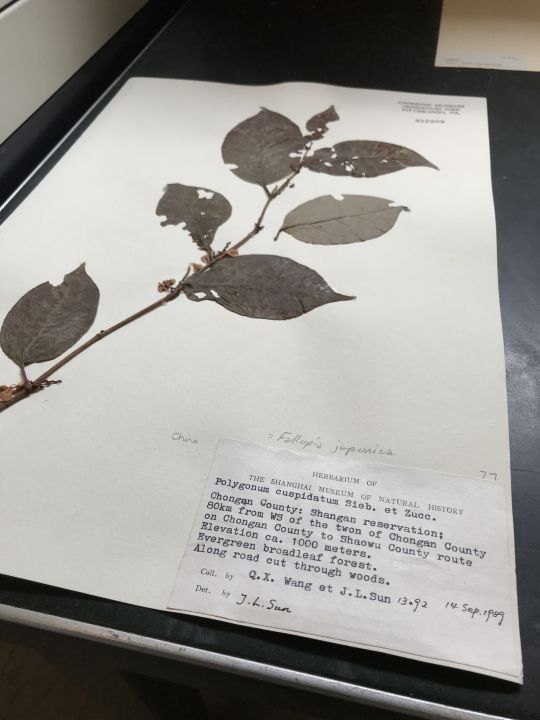

This specimen of Japanese knotweed (Fallopia japonica, formerly known as Polygonum cuspidatum) was collected in China on Sept 14, 1989 by Q.X. Wang and J.L. Sun.

Even if you’ve never been to East Asia, this species might be familiar to you. Although native to China, Japan, and Korea, Japanese knotweed is now common across much of the temperate world, including the United States and Europe. In Pittsburgh, Japanese knotweed (and related introduced knotweed species) form dense stands along rivers, streams, and roadsides.

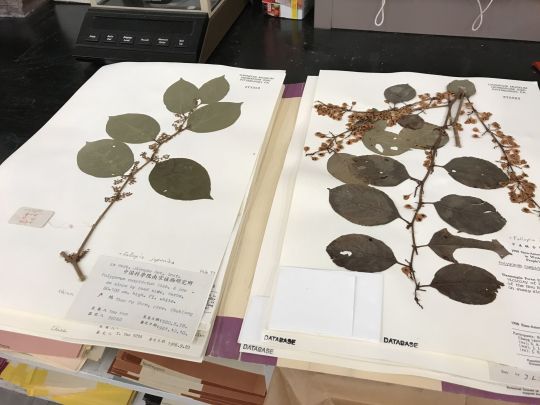

Specimens collected from both the native and introduced ranges can be compared to better understand plant invasions. For example, do invasive species look the same in their home range?

Although Collected On This Day posts tend to be biased towards specimens collected in Pennsylvania, the Carnegie Museum of Natural History herbarium includes specimens from many countries around the world. In fact, about one-third of the 530,000+ specimens are from outside the United States.

How do these species from far away regions end up at the Carnegie Museum? Many are from expeditions from botanists affiliated with the museum – much in the same way locally collected specimens become part of the collection. But many others are obtained through exchange with other herbaria. Many plant collectors often collect duplicate specimens to send to several herbaria. Most herbaria have exchange programs, where specimens (usually duplicates) are exchanged between institutions. This practice functions to build the collection to include new species and specimens. But it also has an important function to safeguard the future of the data. In the case of damage (such as pest outbreaks or even fire, in the recent devastating case at the Museu Nacional in Brazil), having specimens spread across several institutions helps ensure the future of specimens.

Note the label on this specimen shows this specimen was at one time associated with the herbarium of the Shanghai Museum of Natural History.

Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History share digital specimens from the herbarium on dates they were collected. They have embarked on a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022.