For a number of years now in the Section of Invertebrate Zoology (IZ), we have been rearing larvae (= caterpillars) of different species of Lepidoptera (moths & butterflies) for both fun and research. This summer, given the ongoing COVID-19 pandemic and the need for everyone to isolate, I have taken to collecting and rearing a number of different species at home that were collected at a bug sheet in my own back yard (Figure 1).

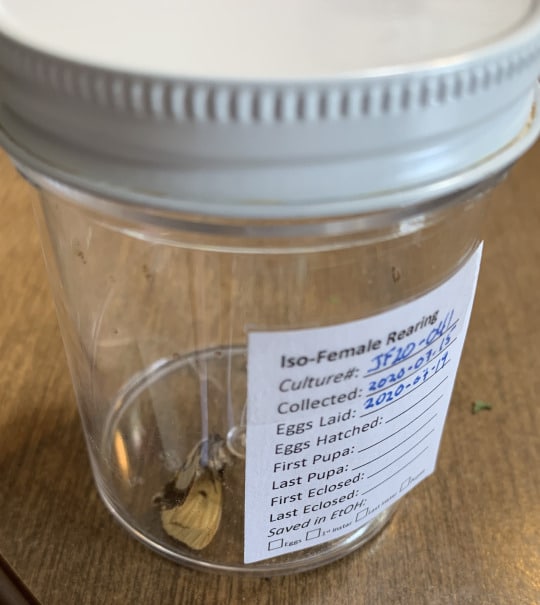

Female moths are collected live and held in a plastic jar we call a “live jar” (Figure 2), until they lay eggs. If eggs are laid, and they are fertile, they usually hatch in about 7-10 days. This gives you enough time to identify the female adult to species (a recent field guide to moths and butterflies is a good place to start) so you can find out information on its preferred food source(s), or host plant(s), before the little larvae hatch are start searching around for food. If the eggs do hatch, rearing the resulting little caterpillars is a fun way to break up the tedium of being cooped-up at home for so long and is a nice way to bring Nature indoors.

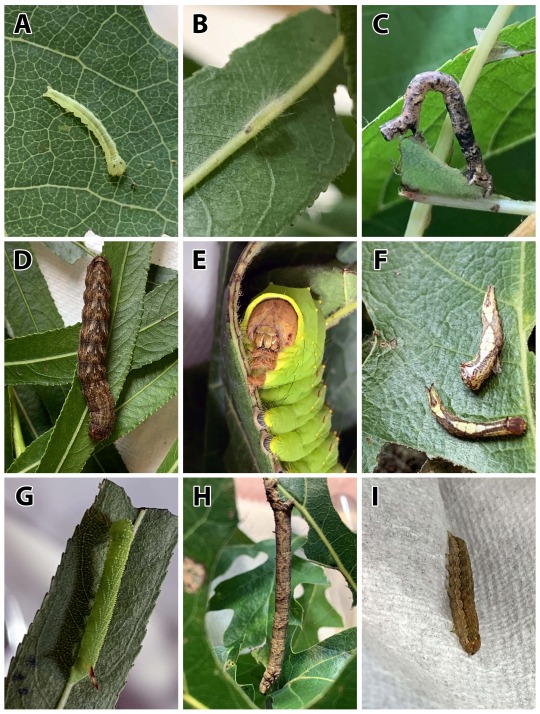

We have a little bit of experience rearing caterpillars at home. As you may know from a previous IZ blog post, my son and I reared some caterpillars that were not yet known to science, which resulted in a small publication. Right now, we have caterpillars of ten different species at various developmental stages. I check on them daily, making sure to keep their containers clean, and provide them with enough food to eat from their preferred host plant (Figure 3). It is amazing how quickly these little guys grow and change, all in the matter of a few short weeks. I try to capture images of them as they develop (see Figure 4), so they can be used on our websites, in blog posts (such as this one), or in eventual scientific publications that may result from the work.

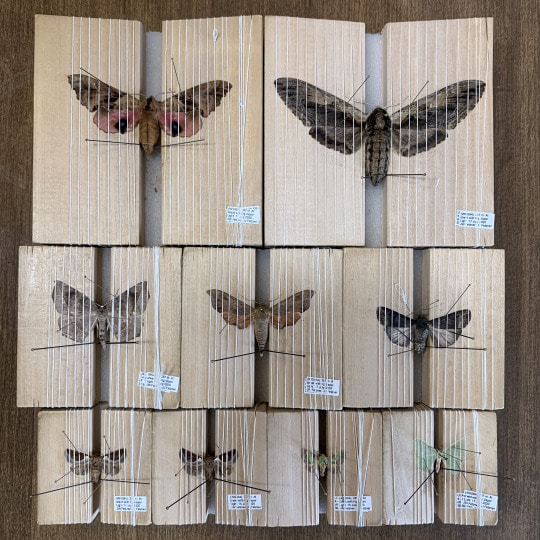

Once the females have laid eggs, they usually die as a result, having completed their task in the moth’s life cycle. The females are then pinned, and the wings are usually spread on wooden blocks until they dry, so that the specimens can be easily identified and examined by experts in the future (Figure 5). They then receive data labels that includes information on the specific locality and date of collection, method of collection, and the collector name(s).

My son and I are looking forward to watching our little menagerie of caterpillars progress throughout the summer, eventually completing their life cycle and becoming adult moths. I’m glad that we are able to give you a glimpse of our progress to date and hope you have enjoyed seeing some of these diverse little spineless wonders. Hopefully, when we can all return to our normal outdoor activities, you will have a newfound appreciation for these amazing insects when you encounter them out in the wild.

James W. Fetzner Jr. is Assistant Curator of Invertebrate Zoology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What are Murder Hornets?