by John Wible

The Naming

En route to Tahiti in 1792, a ship put into Adventure Bay at Bruny Island off the coast of Tasmania, where the captain’s log made the first written account of an animal that was covered in thick, sharp quills with a pointy bill and small mouth. The ship was the H.M.S. Bounty and the captain was none other than William Bligh. In the same year, a specimen from New Holland (Australia) arrived in the natural history department of the British Museum in London where it was formally described by assistant keeper George Shaw. Shaw conceived of this animal as a cross between an Old World porcupine and a South American giant anteater. He named it Myrmecophaga aculeata, a new species in the same genus as the giant anteater, Myrmecophaga tridactyla, and called it by the common name porcupine anteater; its formal name translates to spiny anteater. The animal, about a foot in length, had been found amid an ant hill. Shaw’s account included the first image of the porcupine anteater.

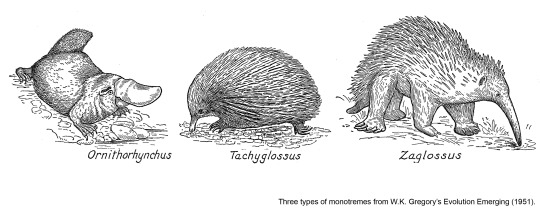

A bewildering number of generic and specific names were applied to the porcupine anteater over the next two decades, reflecting changing views about its taxonomy. The common thread was a realization that this animal had little to do with the South American anteater and, therefore, could not remain as a species of that animal’s genus. Moreover, a second bizarre mammal from New Holland was described by George Shaw in 1799, the duck-billed platypus, Ornithorhynchus anatinus. Most authors recognized a kinship between these two odd forms. Today, we know them to be two types of monotremes or egg-laying mammals.

One of the generic names given to the porcupine anteater was Echidna, proposed by the famous French comparative anatomist Georges Cuvier in 1797. In Greek mythology, Echidna was a hideous, flesh-eating monster with the top half of a beautiful woman and the body of a fearsome snake; Echidna was mother of many other infamous monsters, including Cerberus and Sphinx. For the porcupine anteater, this name was meant to reflect the animal’s mixture of reptilian and mammalian characteristics. However, the generic name Echidna was already occupied, having been given to a moray eel in 1788. So, by the rule of priority, it could not be used for the porcupine anteater. The name Tachyglossus, meaning rapid tongue for the speed with which it ingests ants, was proposed by Johann Karl Wilhelm Illiger of the zoological museum in Berlin in 1811. Thus, was born the formal moniker of Tachyglossus aculeatus for the porcupine anteater. Cuvier’s echidna stuck as the generally recognized common name. A refinement to the common name came later with the description in 1876 of a second kind of echidna from New Guinea. This larger form with an even longer snout was ultimately called Zaglossus, meaning great tongue. These two types have become known as the short-beaked and long-beaked echidnas, which perhaps is unfortunate as we usually think of birds having a beak and there is nothing beaky about the flesh-covered echidna snout.

A final word on the spiny anteater as an alternative common name. This should only be applied to the single species of short-beaked echidna, Tachyglossus aculeatus, found today throughout Australia, Tasmania, and southeastern New Guinea, as it is a true eater of ants and termites, projecting its tongue 7 inches into nests to feed. The three species of the long-beaked echidnas, two of which are critically endangered, are primarily earthworm eaters. They use their long, pointy snouts to probe through soil and extend their tongue only about an inch to get their prey. They do have an amazing adaptation to catching worms: the anterior third of the tongue has a deep groove with three rows of backwardly directed, sharp, keratinous spines. When the mouth is opened, the groove opens; the worm is maneuvered into this groove; and when the tongue is retracted, the groove is tightly closed around the worm. Instead of spiny anteaters, let’s just call them fearsome spiny wormeaters!

John Wible is Curator in the Section of Mammals at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.