by Timothy A. Pearce

Shipworms, which bore into the wood of ships and the pilings of docks have been a menace to mariners for centuries. Recently, however, some sustainable food advocates are pointing to the disreputable creatures as a key to feeding the growing human population.

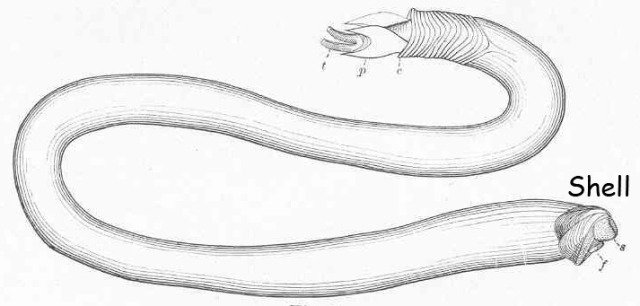

Surprisingly, shipworms are not worms at all, but are a type of clam in the family Teredinidae whose bivalved shells have been reduced to small rasp-like structures at one end of a worm-like body (Fig. 1). Some shipworms grow exceptionally fast, reaching 30 cm (12 inches) in six months. The small shells, which are roughly 5% of the creature’s body length, function as excavators. The shipworm uses the tiny pair to dig into wood, forming a burrow to protect its soft body, and digesting the excavated bits of wood as food. Symbiotic bacteria in the clam’s gills provide the necessary enzymes to digest the wood.

Sailors and stevedores (dock workers) have battled shipworms over the centuries because the holes created by the tiny mollusks weaken the wood, eventually causing ships to sink and docks to collapse (Fig. 2). Consequently, instead of causing yawns, these boring mollusks caused people to take notice. And while the shipworms’ wood-eating regime continues to plague sea-faring people who rely upon wooden vessels, other people are now taking note for a culinary reason.

From baddy to buddy, from scourge to supper, shipworms are undergoing a reputation transformation. As we look to the future, we see staring back at us both the hungry, growing human population and the threat of climate change. We understand the need to produce more food sustainably, including more protein, while reducing our greenhouse gas emissions. As an alternative to methane-belching cattle, some experts have advised eating sustainable protein sources such as insects and shipworms.

Among the advantages of shipworms as food are their exceptionally fast growth, their ability to thrive on a diet of waste wood or sustainable microalgae, and their high protein and omega-3 fatty acids content. (Willer & Aldridge 2020).

Today, shipworms are eaten primarily in parts of southeast Asia. But because they show great promise as a sustainable protein source, they are being considered for aquaculture to help feed the growing human population. In the not-so-distant future, you might be spicing up your meals by including (not so) boring clams!

Keep clam and carry on.

Timothy A. Pearce is the head of the Section of Mollusks at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Literature Cited

Goode, G.B. 1884. Fisheries and Fishery Industries of the United States: Section I, Natural History of Useful Aquatic Animals, Plates. Washington, DC: Government Printing Office.

Willer, D.F. & Aldridge, D.C. 2020. From pest to profit—the potential of shipworms for sustainable aquaculture. Frontiers in Sustainable Food Systems, 4: 575416. doi: 10.3389/fsufs.2020.575416

Related Content

Cuttlefish Pass Marshmallow Test

Ask a Scientist: How did snails evolve from living in water to living on land?

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Pearce, Timothy A.Publication date: July 23, 2021