By Mason Heberling

Biological collections are at the heart of the natural history museum. Biological collections are large and diverse, with specimens of shells, bugs, birds, fossils, bones, plants, and more. They were collected anywhere from the sidewalk in front of the museum this past spring to a remote jungle on the other side of the world a century ago.

Each of the roughly 22 million objects at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History have valuable scientific stories to tell. Knowledge derived from museum specimens motivate or inform nearly every aspect of museum practice. Specimens are used directly in museum exhibitions and programming. Specimens are sources of scientific data, used by researchers both at the museum and across the world to understand the past, present, and future of life. And these specimens continue to be used in new and innovative ways to inform us about the world and the impact of humans in the Anthropocene.

Collecting from nature for admiration and study is an ancient practice, with plant collecting among the oldest. The oldest known collection of plants, known as an herbarium (plural: herbaria), dates to 16thcentury Italy!

But specimen collecting is not a dated practice; it is not just something botanists used to do. Plant collecting remains to this day an active and necessary part of botanical science. With over half a million plant specimens, the Carnegie Museum herbarium is not stagnant. Our collection continues to grow. New specimens are collected and added to the herbarium each year, expanding the scope of the collection and therefore its scientific and societal relevance. In fact, in the recent era of rapid environmental change, new collections are all the more important.

Despite the continued importance of this practice, the standard process for collecting new specimens has change remarkably little through time. Major changes in collection practices include the use of GPS coordinates and to a lesser extent, specific sampling methods for genetic analyses.

In the Section of Botany, Bonnie Isaac (Collections Manager) and I are developing innovative ways to maximize the future use of our collections. One way we are doing this is by linking our collections to the popular citizen science platform, iNaturalist (inaturalist.org). iNaturalist is a free resource available online or as a mobile app that allows users to record biodiversity observations. We are using iNaturalist in the field and in the herbarium to facilitate new collections and expand the research value of specimens.

Before collecting a specimen, we take images in the field of the specimen in real life. These images are uploaded to iNaturalist, including other data such as date, time, location, and species identification. Other iNaturalist users can also contribute directly through verifying the identity of the specimen or making other comments.

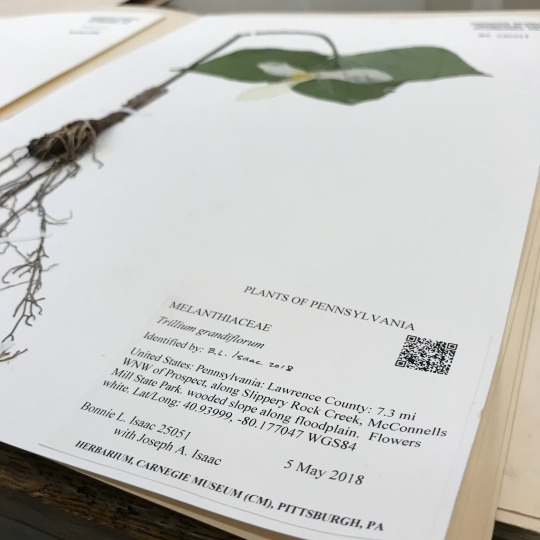

Back in the herbarium, we export this information from iNaturalist to create unique herbarium labels for each specimen. We are using QR codes to link the specimens to the online iNaturalist observation. These QR codes can be read by most mobile devices. Among other information, the iNaturalist observation account online permanently links images from the field to the physical specimens in the herbarium.

What color were the flower petals? What was the size of the plant? Did it have a unique pattern on the bark? What was the branching pattern? These questions and more can be asked to place herbarium specimens in a more complete context.

We envision a future where researchers can go through the herbarium with a mobile device such as a tablet or smart phone, scan QR codes on specimens, and be immediately directed to images of the specimen in the field.

Our article outlining this approach is available for free online:

Heberling, J. M., and B. L. Isaac. 2018. iNaturalist as a tool to expand the research value of museum specimens. Applications in Plant Sciences 6(11): e1193. https://bsapubs.onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/epdf/10.1002/aps3.1193

Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Check back for more! Botanists at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History have embarked on a three-year project to digitize nearly 190,000 plant specimens collected in the region, making images and other data publicly available online. This effort is part of the Mid-Atlantic Megalopolis Project (mamdigitization.org), a network of thirteen herbaria spanning the densely populated urban corridor from Washington, D.C. to New York City to achieve a greater understanding of our urban areas, including the unique industrial and environmental history of the greater Pittsburgh region. This project is made possible by the National Science Foundation under grant no. 1801022. Any opinions, findings, and conclusions or recommendations expressed in this material are those of the author(s) and do not necessarily reflect the views of the National Science Foundation.