For inhabitants of Western Pennsylvania, the word ‘fox’ as applied to an animal is usually reserved for the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) because if you have seen a fox in an urban area, that is the most likely one you would have seen. Although chiefly nocturnal in its habits, red foxes do venture out during daylight hours. But the red fox is only one of 23 different species of foxes. In fact, 61% of all species in the canid or dog family are foxes; the remainder are dogs, wolves, and jackals.

You might be wondering, what exactly is a fox? A fox is a canid that is distinguished by its pointy snout and bushy tail. In fact, fox comes from an old Germanic word for tail. The collective noun for a group of foxes is a skulk, a leash, or an earth. Males foxes can be referred to as dogs, reynards, or tods, females as vixens, and young as kits, pups, or cubs.

Not all foxes are closely related to each other. There are three main groups. One group is found exclusively in South America and includes eight species; a second group of two species is found in the Americas; and the third and largest group, which includes the red fox, is found all over the world except in South America and Antarctica.

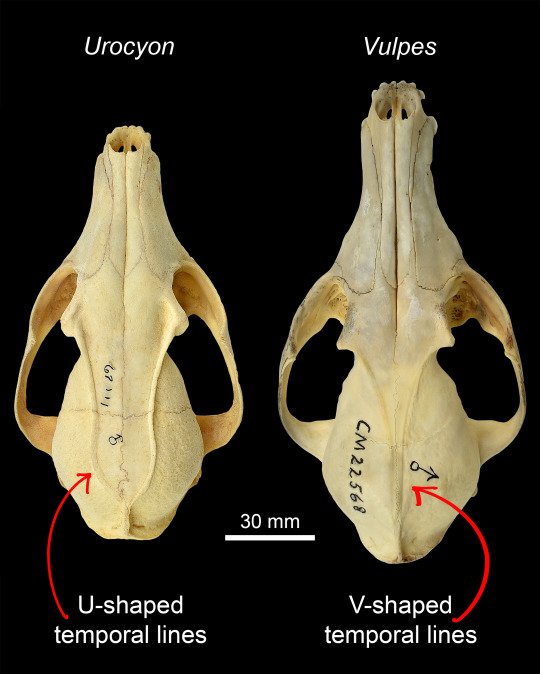

All foxes look like foxes, but they display a remarkable array of behaviors and lifestyles depending on where they live. The two species found in Western Pennsylvania are the red fox (Vulpes vulpes) and gray fox (Urocyon cinereoargentatus). These two are distinguished by their coats, as well as a useful feature on their skulls. Mammals that have strong chewing muscles have prominent ridges on their skulls for muscle attachment. These are called temporal lines. As seen in the photo below, the gray fox has U-shaped temporal lines (i.e., U for Urocyon) and the red fox has V-shaped temporal lines (i.e., V for Vulpes). A convenient coincidence for biologists!

One of our favorite foxes is the Fennec fox (Vulpes zerda). This is the smallest living fox weighing in at less than two kilograms but despite its diminutive size it has the greatest ear size to body size ratio of any fox (see picture below). This little fox is a true survivor, living in one of the harshest environments on the planet: the shifting sand dunes of the Sahara Desert. Their huge ears act as amplifiers providing them with acute hearing for hunting and capturing prey at night. Their ears have an additional purpose – temperature regulation (quite important when you live in one of the hottest environments on Earth). Fennec foxes use the large surface area of their ears to cool their blood. Like dogs, Fennec foxes also have another adaptation for regulating their temperature – they pant. They only start to pant when temperatures reach 95°F, and their breathing rate can increase from 23 breaths per minute to 690 breaths per minute! Get a closer look at a Fennec fox in the Hall of African Wildlife on the second floor of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Sarah Shelley is a postdoctoral research fellow and John Wible is Curator in the Section of Mammals at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.