How did it get here? This question is often asked but rarely answered in the museum’s exhibits. Follow the journey of objects that have never been on view—from their creation to our current work preparing for a new exhibit about ancient Egypt.

Stories from Siwa

Why were they made?

Preserving crafts

The fertile desert oases in Egypt are centers of life amidst the sands. One of these is Siwa Oasis, an area just south of the Mediterranean coast. Siwa was a vital commercial hub in ancient times, because of its location and richness of natural resources like water, dates, and palms. Siwa is an important cultural center for the Amazigh people, an ethnic minority who live in North Africa.

Siwans have preserved many traditional crafts and customs including jewelry-making, intricate embroidery, baskets, and pottery in unique styles. The objects on view here are examples of traditional crafts that relate to important events in the lives of Siwan women.

How did these get here?

Cassandra Vivian

Pennsylvania native Cassandra Vivian taught at the American University in Cairo. From 1978–1988, she traveled throughout the Egyptian oases with the goal of documenting the lives of local women. She purchased a large collection of items (including dresses, jewelry, baskets, rugs, and pottery), many of which she donated to the museum.

The American University in Cairo (AUC) was established when Egypt was still under British occupation. AUC is part of a legacy of colonialism. It enabled American scholars to establish valuable relationships and gain access to Egyptian culture, history, and ways of life.

What’s happening now?

“I Want to Speak about Ordinary Hidden Treasures“

Community fellow Mina Milad is an Egyptian artist and archeological draftsman based in Cairo. When choosing objects to include here, he was inspired by Siwa’s bright colors and detail-oriented craftsmanship, which is less represented in museums than Egypt’s pharaonic past.

The people of Siwa Oasis are one example of the many cultures in Egypt that thrive today. Mina explained that he painted this portrait to highlight Egypt’s many beautiful cultural treasures and different heritages.

Learn more about the objects in the collection

Special Thanks

Community Fellow: Mina Milad Ramsis Khela Attaalla

Arabic translation by Global Wordsmiths

Additional thanks to Dr. Mostafa Sherif and Derek Wessel

Sacred Scents

The use of incense is a bridge between ancient and contemporary Egyptian traditions. These objects trace the evolution of incense’s religious use from ancient Egypt to the Coptic Church.

Incense: Why was it made?

Connections Across Time

In ancient Egypt, incense was a vital part of religion and funerary rituals. Priests used incense to cleanse spaces and please the gods. A ritual known as ‘the opening of the mouth’ used incense to bring life to the dead and to images of people and gods.

Thousands of years later, the Egyptian Coptic Church—one of the oldest Christian churches in the world—still observes similar traditions, also using incense to purify spaces and represent life after death.

How did they get here?

Private Collectors

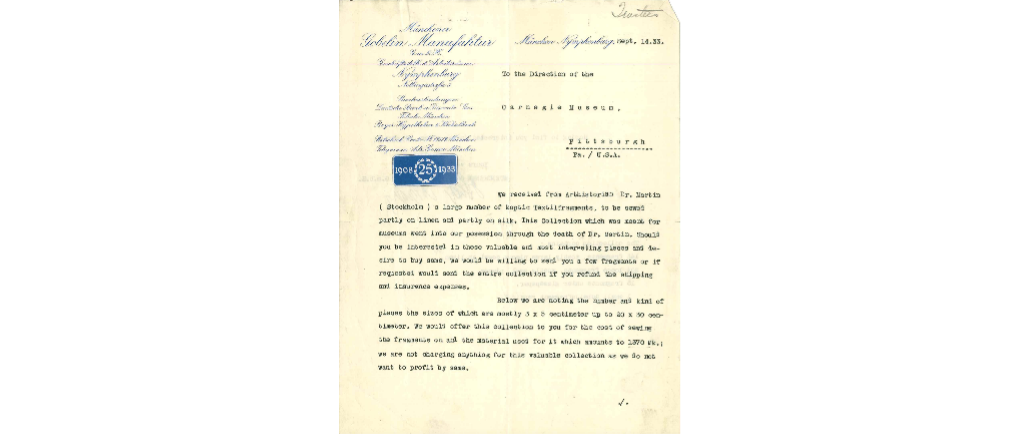

The exact origin of these textile fragments are unknown. It was purchased by the museum from a German manufacturing company, who acquired them from the estate of Fredrik Robert Martin, a Swedish antiquities collector and dealer.

During the “Golden Age” of Egyptology, in the late 1800 and early 1900s, Western collectors and museums benefitted from the unjust colonial occupation of Egypt. When people remove artifacts from their original locations it makes it much more difficult to understand how and why they were made.

What’s happening now?

Community Perspectives

“Coptic history is precious,” says Veronica Nashed Ghaly, museum community fellow and parishioner at St. Mary’s Coptic Orthodox Church, Pittsburgh’s only Coptic Church. She cherishes the way artifacts connect her Egyptian and Coptic heritages. She was moved by the fragment showing Jesus because it is evidence of the long history of the Coptic Church in Egypt.

In the 1950s, many Copts fled to the United States to avoid religious persecution. Veronica recognized that museums play a vital role in caring for and displaying important objects of Coptic history that might otherwise have been lost to acts of violence.

Under Your Nose

Bouquets of Nature

Powerful smells can transport our imaginations across time and space. In ancient Egypt, temples were filled with the woodsy smoke of frankincense, myrrh, and other incenses.

Learn more about the objects in the collection

Special Thanks

Community Fellow: Veronica Nashed-Ghaly

Arabic translation by Amer Kebty, Global Wordsmiths.

Additional thanks to Dr. Kathleen Sheppard, Missouri University of Science and Technology; Father Daniel Naklah, St. Mary’s Coptic Church; Dr. Travis Olds, Assistant Curator of Minerals, Carnegie Museum of Natural History; Dr. Mark E. Bier, Research Professor and Director, Center for Molecular Analysis, Department of Chemistry, Carnegie Mellon University; Nicole Auvil, Ph.D. Student, Department of Chemistry, Carnegie Mellon University

Amarna

The first set of objects that we’re highlighting comes from Amarna, once the site of a short-lived ancient Egyptian capital city. Use the interactive map to follow their journey from Egypt to Pittsburgh.

Why were they made?

around 1347 – 1345 BCE

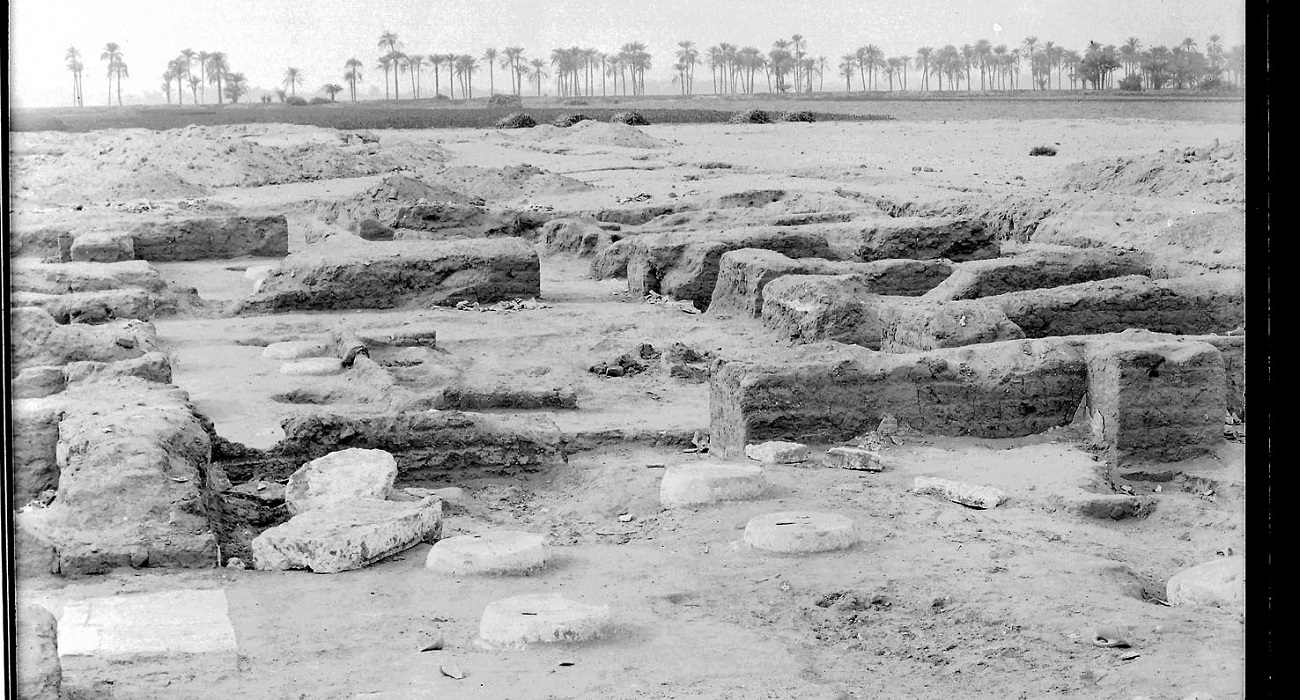

Early in his reign, king Akhenaten ordered a new capital city to be built on a sunny strip of desert. Ancient Egyptian craftspeople made these objects for the Maru-Aten, the king’s new solar temple.

How did they get here?

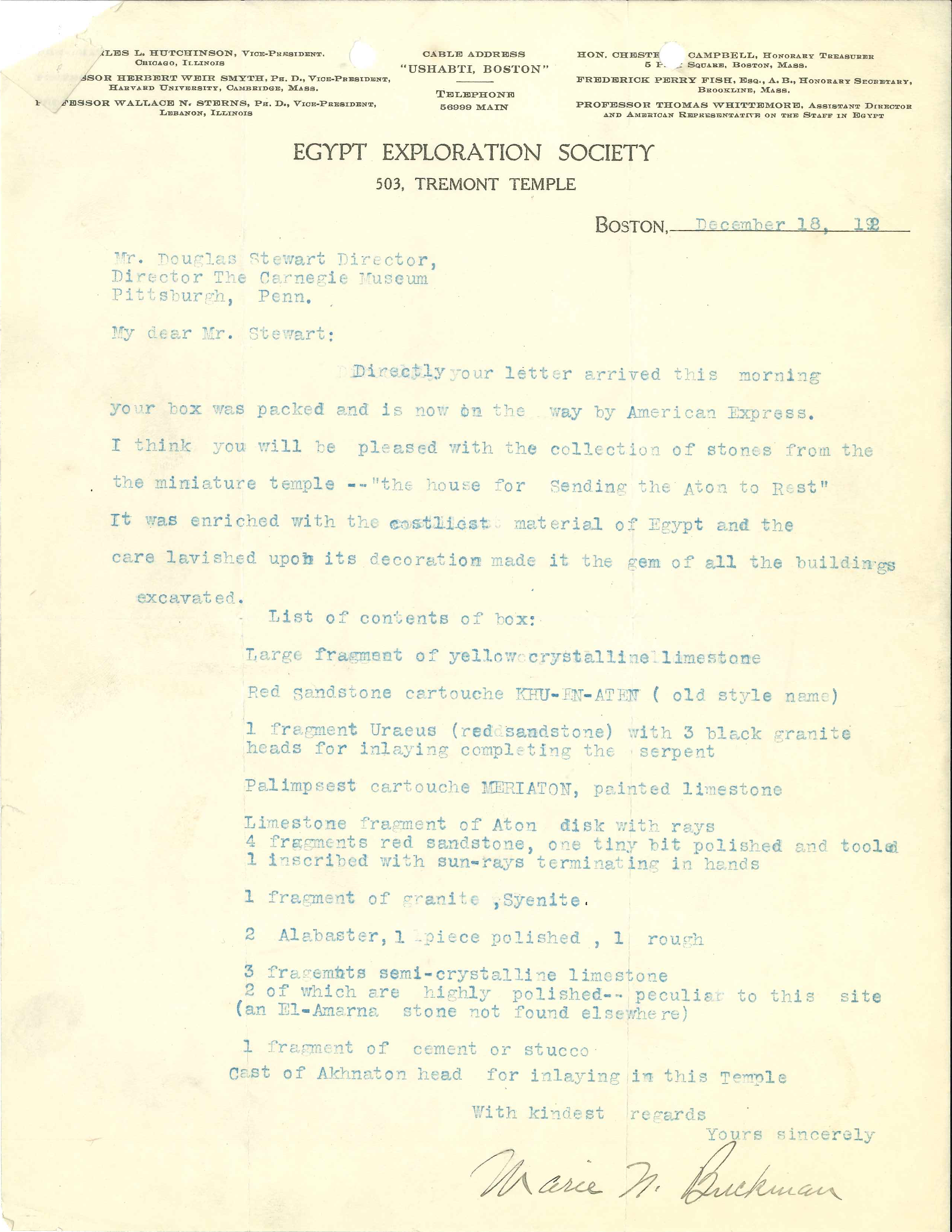

1921 – 1922 CE

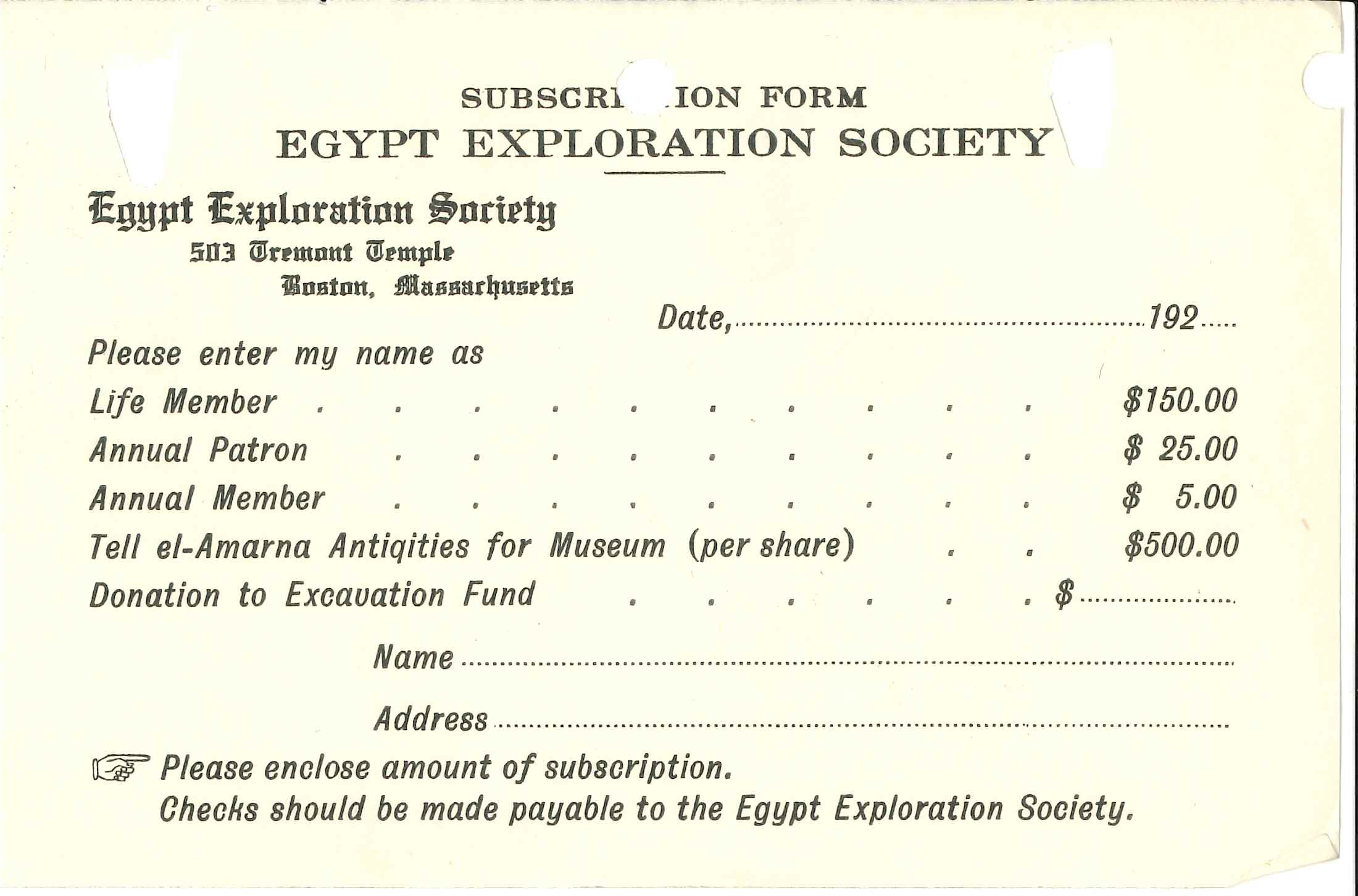

Archaeologists from the Egypt Exploration Society uncovered pieces of Akhenaten’s ancient solar temple. In return for a small sponsorship fee, the museum received 23 objects from the site.

In 1882, the British-run Egypt Exploration Society (EES) was founded to do yearly archaeology. At the same time, Great Britain began a decades-long military occupation of Egypt. Its power in Egypt allowed the EES to send the objects they uncovered around the world.

What’s happening now?

Today

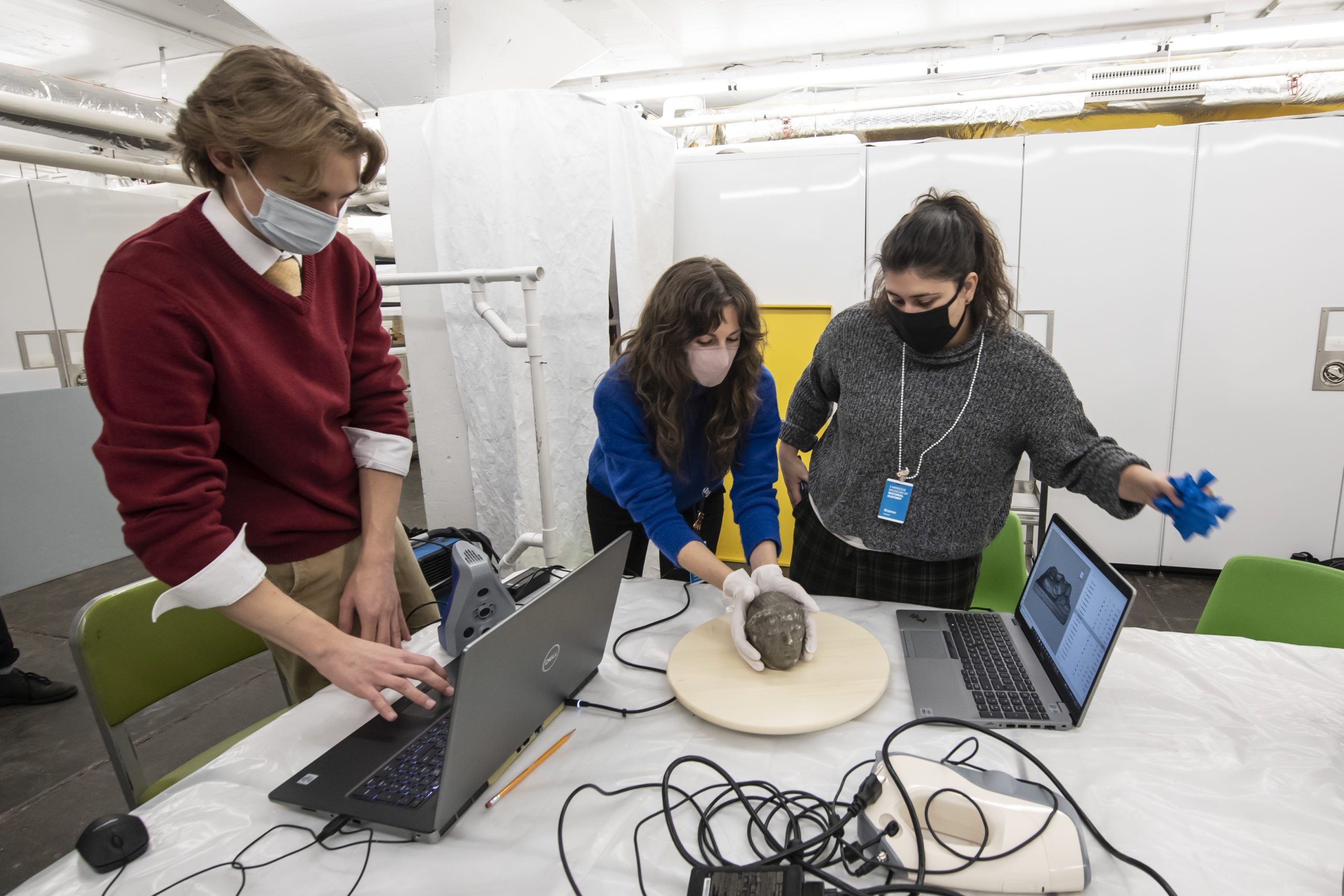

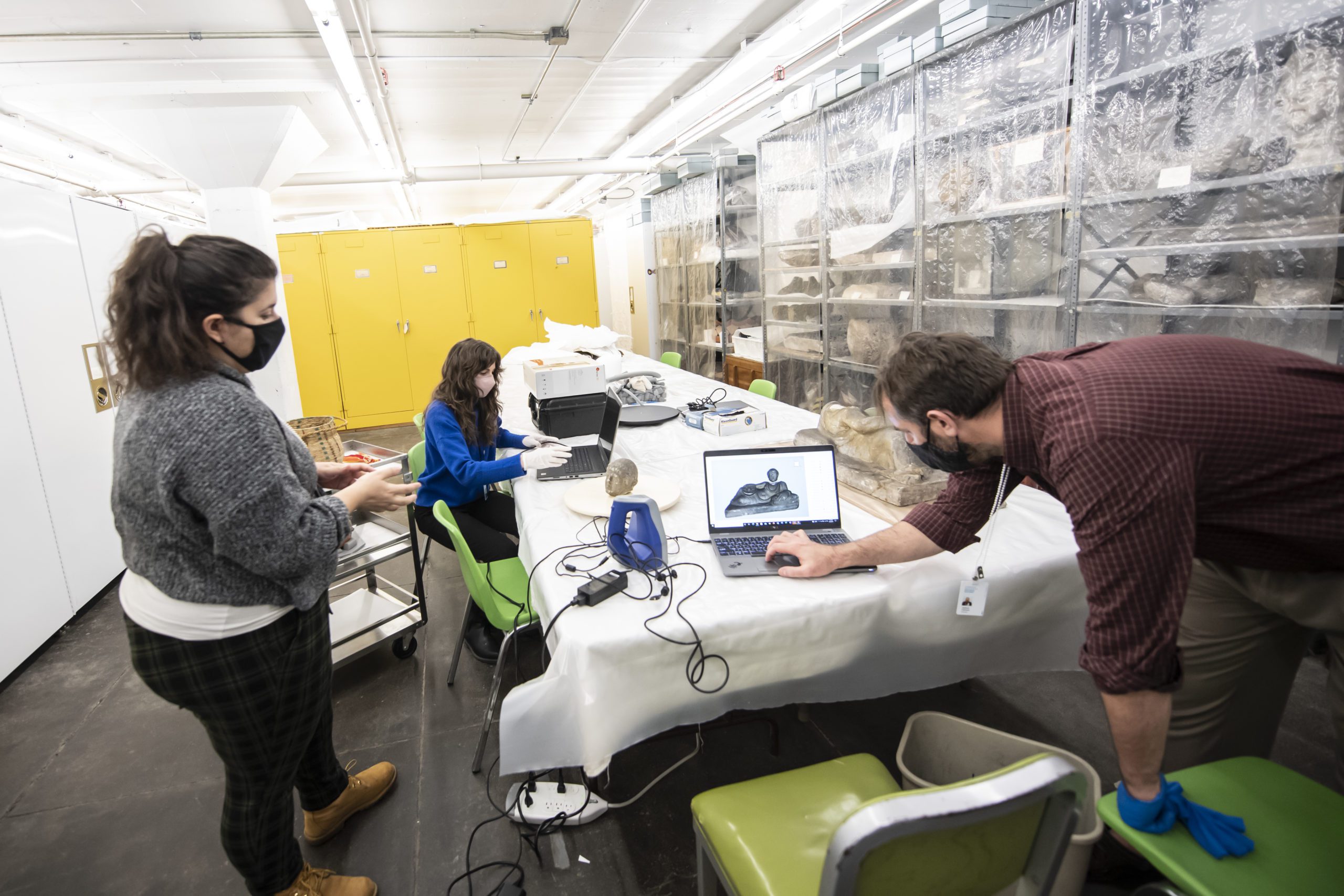

After 100 years in storage, these pieces are on display for the first time. The museum is looking at them in a new light to help us examine our collecting practices.

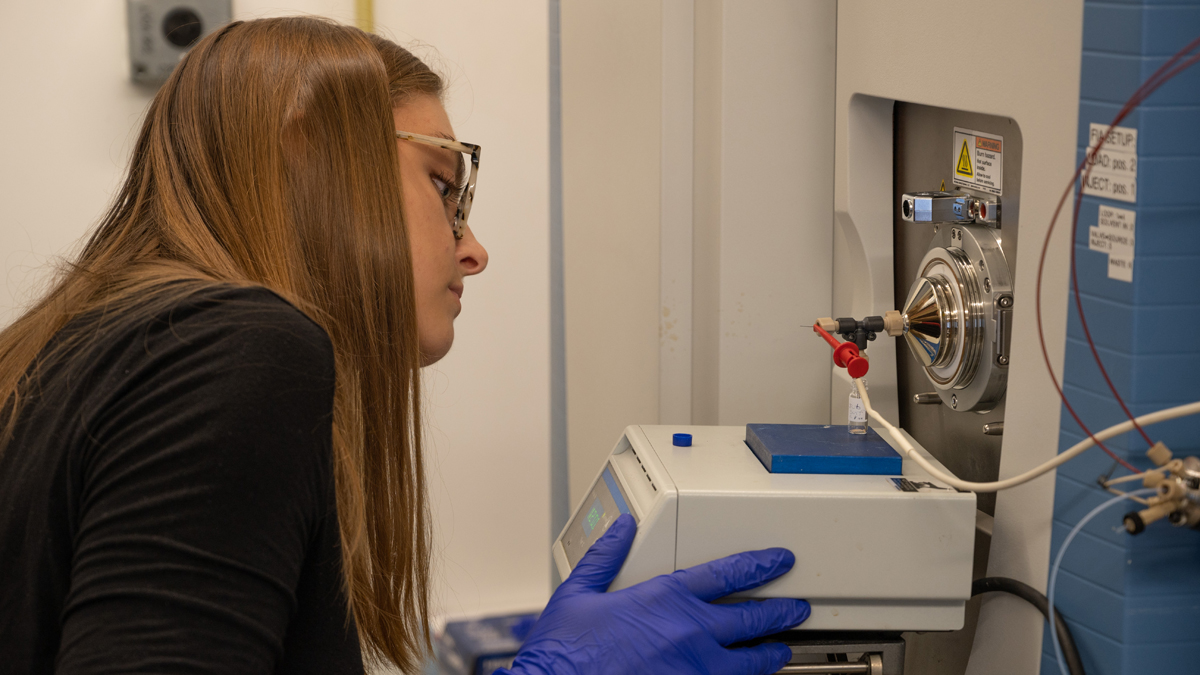

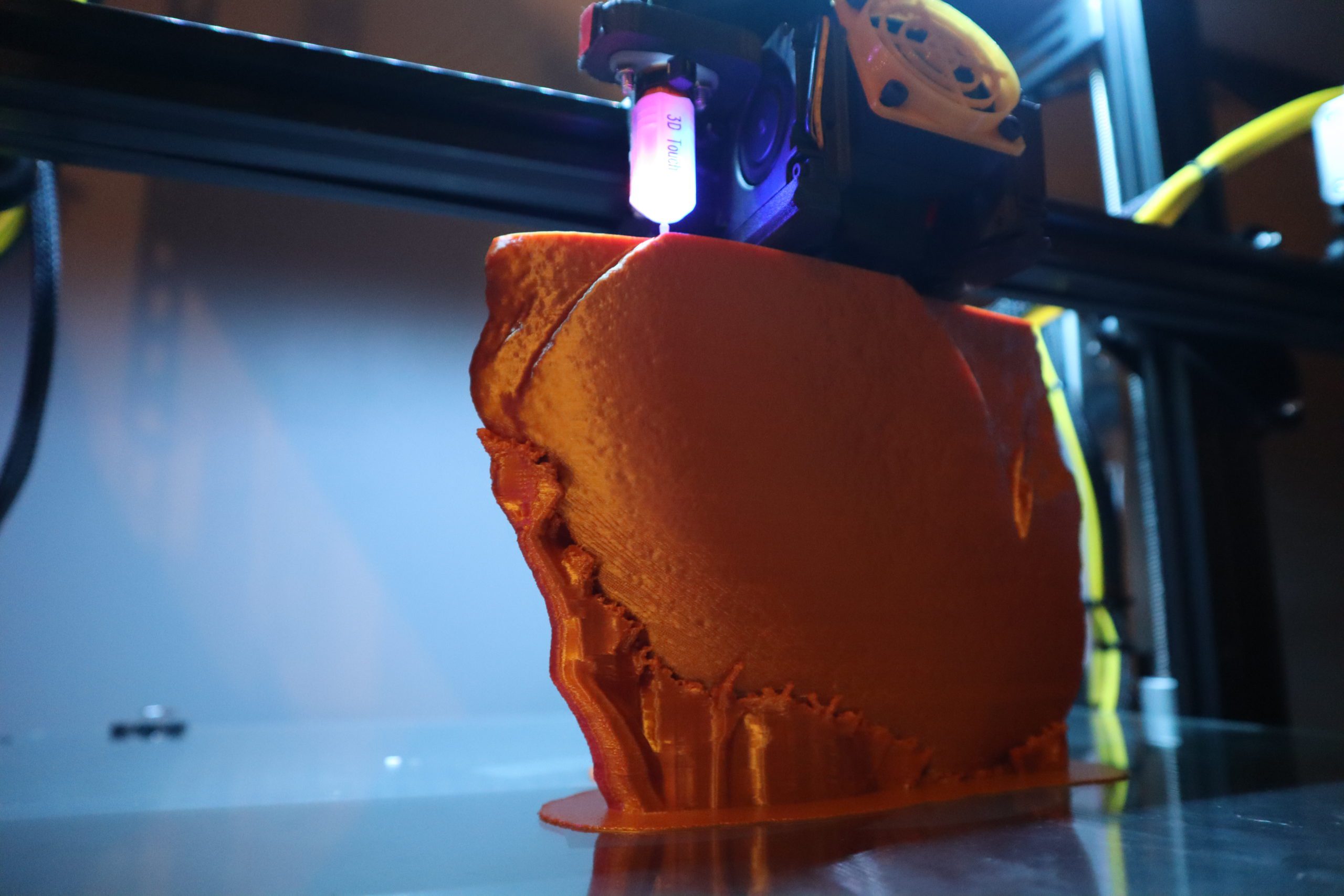

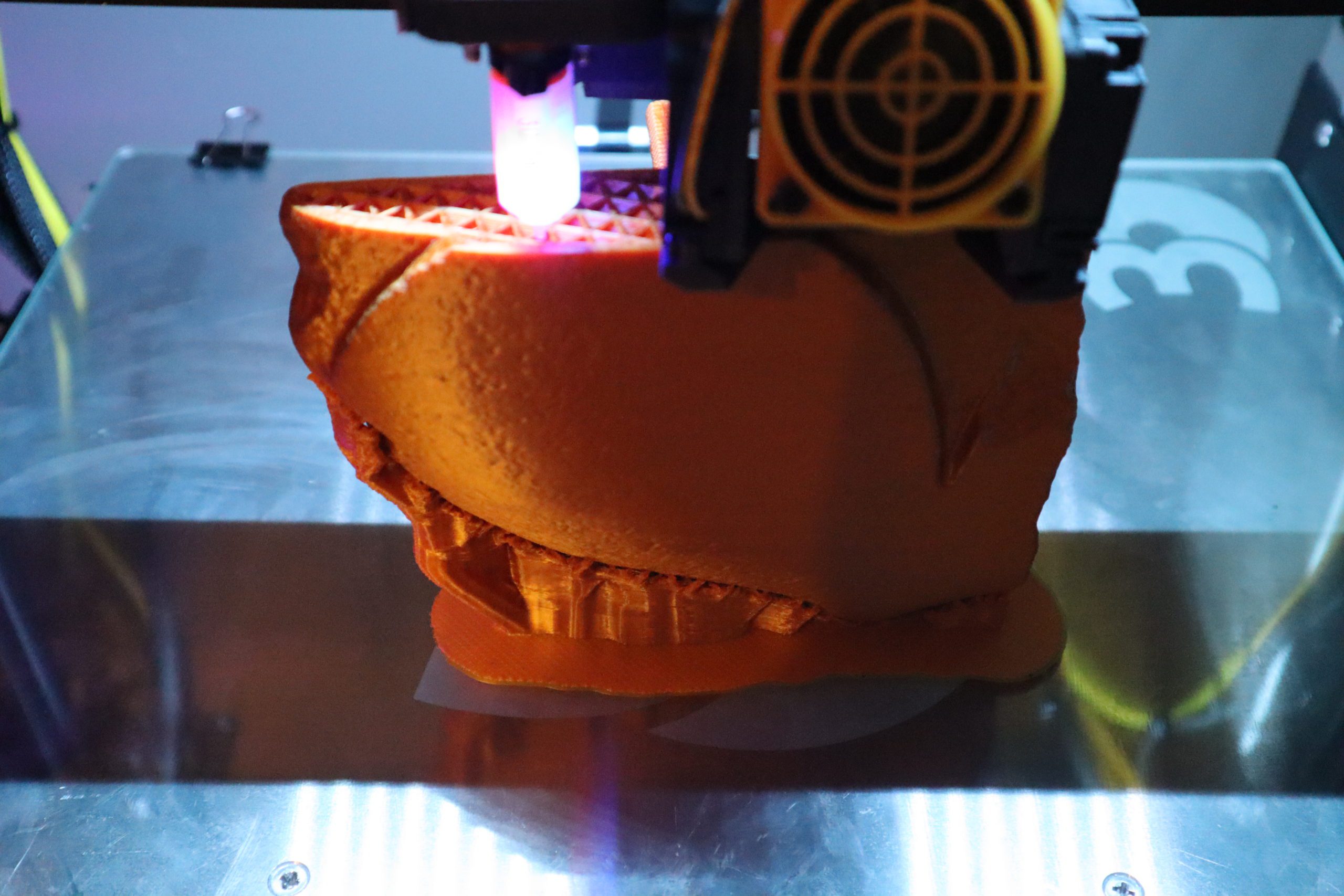

Museums are part of unjust colonial systems that separate people from their cultural heritage. Researchers are currently using 3D scans to digitally reunite fragments of king Akhenaten’s capital city that are spread across the world.

Learn more about the objects in the collection

With Special Thanks

3D models were created by members of the University of Pittsburgh Honors 3D Scanning program: Helena Hyziak, Brianna Stellini, Charlie Taylor, Derek Wessel, and Emily Wiley. Program co-directors: Dr. Josh Canon (University of Pittsburgh, Honors College), Dr. Lisa Saladino Haney (Carnegie Museum of Natural History).

Purchase of the Artec3D scanners was made possible by Carnegie Discoverers.