by Lisa Miriello

After the Fern Hollow Bridge collapse on January 28, 2022, many commuters found themselves experiencing some traffic headaches as they scrambled to find different ways to and from work or school. My new route takes me past The Frick Pittsburgh, a museum complex in the Point Breeze section of Pittsburgh that includes Clayton, the former home of industrialist Henry Clay Frick.

As someone who works in the Section of Mammals, my thoughts while passing the stately grounds often turn to Frick’s son Childs (1883-1965), who grew up here exploring the woods surrounding the estate and attending Sterrett School (now Sterrett Classical Academy), less than a third of a mile away.

As Childs grew older his early interest in the natural world turned to more scientific pursuits, and he embarked on a series of collecting expeditions in North America followed by visits to Africa, first in 1909 and again in 1911. But Childs wasn’t looking for “trophies.” By collecting animals at different life stages his goal was to further the knowledge of the lifestyle and habitats of these unfamiliar animals. Many of these specimens were gifted to the Carnegie Museum, and as the shipments arrived from overseas the staff taxidermists had their hands full.

Led by brothers Remi and Joseph Santens these skilled artisans created expressive animal likenesses rather than the static displays that were seen in most museums at the time. Both Santens even visited zoos in New York and Washington, DC, to study the movements of living animals. Preserved plant life from Africa provided even more authenticity to the displays. The African Buffalo (Syncerus caffer) group was especially notable in how it was depicted. The animals appear to be spattered with mud and tramping through brush, a display then-Director W. J. Holland believed to be the first instance in which exhibition specimens had been accurately placed within their supporting environment. In the Carnegie Museum’s 1913 Annual Report he wrote that the group “may possibly provoke comment and criticism, but it is believed to be a step in the right direction, and will likely be followed by the leading taxidermists of the future.“ You can see the African Buffalo, along with other specimens collected by Frick, in the museum’s Hall of African Wildlife.

While Childs enriched the collection of the natural history museum, other family members left an impact on the city of Pittsburgh as well. His father, Henry Clay Frick (1849-1919), bequeathed 151 acres of land that would become Frick Park. Expanded by hundreds of acres over the years, it’s now the largest of the city’s parks.

Childs’ sister, Helen Clay Frick (1888-1984), was an art collector like her father and helped establish the Henry Clay Frick Fine Arts Library at the University of Pittsburgh. She later had the Frick Art Museum constructed on Clayton’s grounds to showcase her collection of art. This cultural resource opened to the public in 1970.

At the end of the day, as my car inches past the peaceful grounds of Clayton, I imagine traffic must have looked a little different over a hundred years ago when “horseless carriages,” horse-drawn vehicles, trolleys, and bicycles all shared the same road in a free-for-all. Today, with traffic signals and defined lanes, at least it’s more of an ordered chaos.

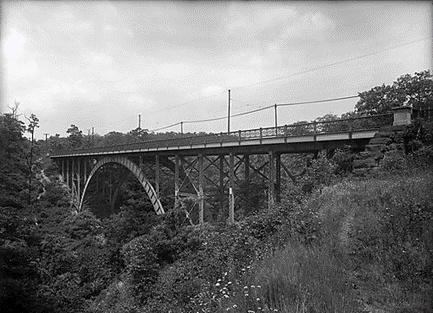

Grant Boulevard | Historic Pittsburgh

Museums and parks can provide welcome relief in a chaotic world, and the Frick family’s contributions to these sanctuaries of art, science, and nature will be enjoyed for generations to come.

Lisa Miriello is the Scientific Preparator for the Section of Mammals.

Related Content

Finding Answers: From Museum to Mountains and Back Again

Meet the Mysterious Mr. Ernest Bayet

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Miriello, LisaPublication date: June 10, 2022