by John Wible

January 21, 2023 was Squirrel Appreciation Day! With Groundhog Day, which commemorates our most famous squirrel, Punxsutawney Phil, right around the corner, I thought it appropriate to celebrate squirrels with this blog.

Rodents are the most diverse lineage of living mammals with more than 2,500 species, which represents nearly 40% of the species diversity of living mammals. Squirrels (Sciuridae) are one of 36 families of living rodents. There are nearly 300 species of squirrels found in the Americas, Eurasia, and Africa; a few squirrels have been introduced into Australia by humans. Broadly speaking, there are three main types of squirrels: tree, ground, and flying. Tree and ground are descriptive of their main habitats; flying squirrels also inhabit trees but are so called because of their unique locomotory pattern, which actually isn’t flying but gliding! Regarding their evolutionary relationships, all flying squirrels are more closely related to each other than to other squirrels, supporting a single origin of gliding in their common ancestor. The tree and ground squirrels do not show the same pattern; all ground squirrels are not each other’s closest relatives and the same is true of all tree squirrels. The fossil record (see text below) supports tree life as the earliest squirrel habitat, with multiple episodes of ground invasion from the trees.

In Pennsylvania, we are fortunate to have seven native species of squirrels (two ground, three tree, and two flying). You can learn more about Pennsylvania mammals at our website: https://mammals.carnegiemnh.org/pa-mammals/

Allegheny County has six of the seven PA squirrel species: the two ground squirrels (the Eastern chipmunk, Tamias striatus, and the groundhog, Marmota monax); the three tree squirrels (the gray squirrel, Sciurus carolinensis, the fox squirrel, Sciurus niger, and the red squirrel, Tamiasciurus hudsonicus); and one of the two flying squirrels (the Southern flying squirrel, Glaucomys volans). Depending on where you are in Allegheny County, you may see all six squirrels, although the Southern flying squirrel is likely the most elusive because of its nocturnal (nighttime) activities.

Squirrels have a long evolutionary history. The oldest fossils identifiable as squirrels first appeared around 34 million years ago in western North America, all showing adaptations to tree life. One of these, Protosciurus, is on display at the Smithsonian in Washington, D.C. (see below). Its skeleton is remarkably like those of living gray squirrels, both in size and morphology. Given that this remarkable similarity occurred over 30 million years of geological time, scientists consider our gray squirrel and tree-adapted relatives to be living fossils, that is, not dramatically changed compared to their very ancient relatives.

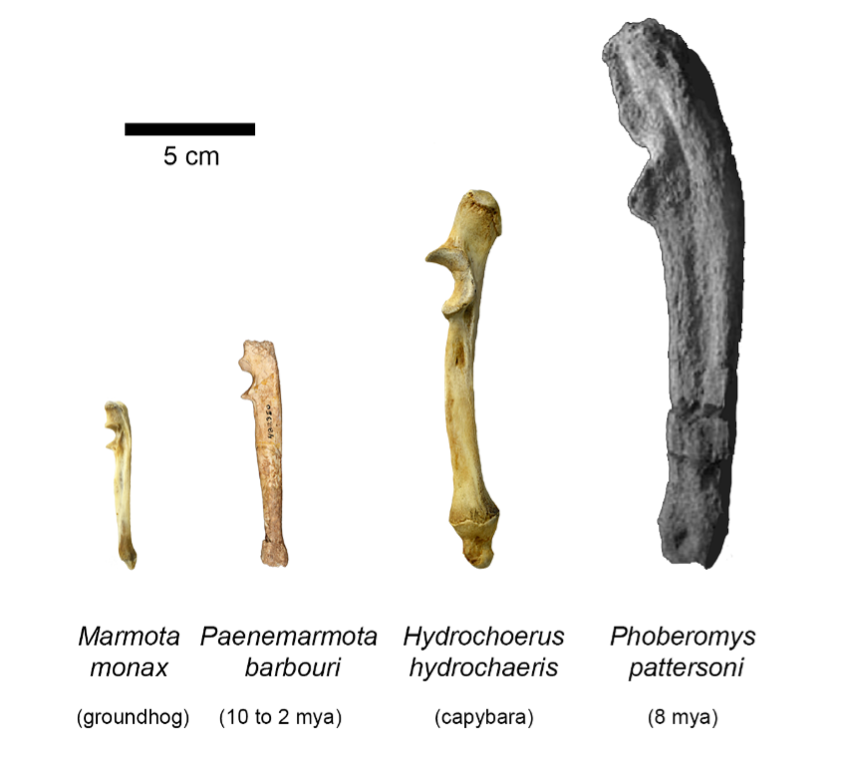

Most rodents are small mammals; think mice and their relatives. Punxsutawney Phil is the second largest living squirrel; his cousin, the hoary marmot, Marmota caligata, from the Pacific Northwest is slightly larger, with adult males typically over 20 pounds. There was a larger ground squirrel that lived in western North America between 10 and two million years ago, Paenemarmota, a Latin name that translates to “almost a marmot.” Some of my colleagues have called it the “giant marmot,” which should be taken with a gigantic grain of salt! Below is an image of four ulnae, one of the two bones in the forearm. On the left is the living groundhog and next to it is the “giant marmot.” Anatomically, the bones are nearly identical, with one a little larger than the other. Weight estimates for the “giant marmot” are around 35 pounds. Yes, that is big for a squirrel, but not compared to some truly giant rodents. Next to the “giant marmot” is the ulna of the largest living rodent, the semiaquatic Central and South American capybara, Hydrochoerus, which translates to “water pig.” Capybaras, which can grow to nearly 150 pounds, are related to guinea pigs! But wait, there is more. Capybaras pale in comparison to the largest rodent that ever lived. The 8-million-year-old Proberomys from Venezuela was estimated to be the size of a large African antelope at 300 to 550 pounds. Yikes, now that is a giant guinea pig.

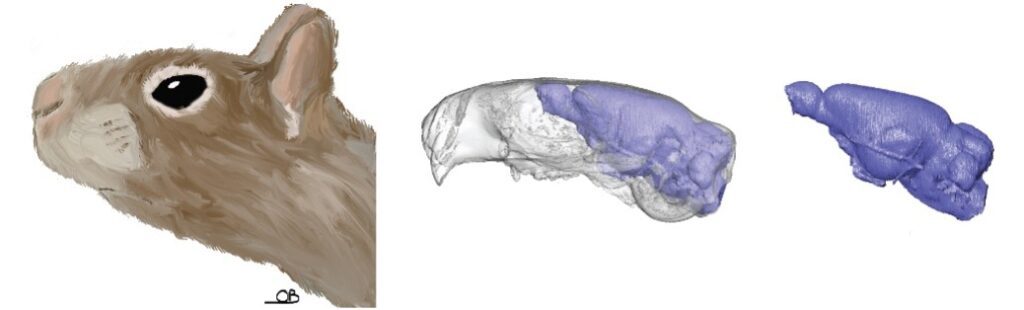

Recently, one of my colleagues, Ornella Bertrand from the Universitat Autònoma de Barcelona, Spain, and coauthors have studied the evolution of the brain in squirrels. From CT scans of fossil skulls (see images below), they were able to recreate various parameters of the brain, including the relationship between brain size and body size. They found that squirrels living in trees had larger brains to their body size than other squirrels, that life in the complex arboreal environment was a driver of brain evolution in squirrels. The result of this evolutionary story for us may be that we will always be hard pressed to build a bird feeder that those big-brained tree squirrels can’t get into!

John Wible, PhD, is the curator of the Section of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Wible, JohnPublication date: January 31, 2023