Museum collections play a significant role in helping scientists answer questions about biodiversity and in providing data that may be used for conservation studies. Every specimen in the Invertebrate Zoology collection tells a story and all together they contribute to the story of life on Earth. Picture it, millions of specimens prepared and labeled. Each has a story to tell about where, when, and how it was collected. This critically important data is also gathered when samples are collected in the field.

The next step is processing the sample and picking specimens to be prepared. So, how do we prepare specimens? Lepidoptera (moths and butterflies) are usually pinned in the field or preserved in the freezer and then pinned and spread in the lab. Most non-Lepidoptera are preserved in alcohol and prepared in the lab. Preparation techniques differ, therefore, with what is being collected.

High quality scientific preparation is important, not just for aesthetic reasons but also for a specimen’s future in the service of research. In some situations, characters on the bodies of the specimens need to be viewed under a microscope, sometimes segments need to be counted to identify a species, and more excitingly, a new species might need to be described from a series of specimens.

Handling of specimens that will be prepared needs to be done when the specimens are flexible—either from an alcohol sample, or a dry specimen that was rehydrated overnight. The pin should be inserted within the thorax, which is the mid region of the body. Insects are bilaterally symmetrical (left and right sides are duplicates), so the pin is always inserted slightly to the right of the midline. This will preserve the integrity of the midline which might possess unique characters that are not duplicated.

In 2018 a culture of Callosamia promethea caterpillars were reared. A record of each stage of metamorphosis was preserved in alcohol and stored with reared caterpillars in the collection. Some of the cocoons were kept alive to allow the adult moths to emerge. The adults were then preserved in the freezer so they could be prepared and added to the collection as a record of the offspring from that culture.

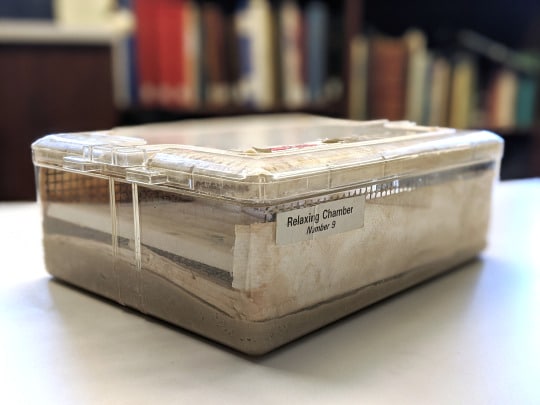

The moths were placed in a humidifying chamber overnight. This chamber is kept humid by adding water to the absorbent paper towels that are layered in above a layer of sand mixed with an antifungal agent that keeps the specimens from getting moldy.

The specimens were thawed, and moisture kept the specimens relaxed enough to handle. Specimens were pinned through the thorax and placed in a wooden pinning block designed for spreading the wings.

A series of very thin pins (size #000) were used to arrange the wings by carefully moving the forewings up high enough to expose the hindwings. String was then wrapped around the block to hold the wings down and allow the specimens to dry. Spread specimens remain on the spreading blocks for about a week to ensure they are completely dry and remain in the desired position. Spreading moths and butterflies allows for all the characters on the hindwings to be visible, and it also allows the underside of the specimen to be viewed more easily. The string is carefully unwrapped a week later, and specimens are removed from the blocks and ready to be labelled.

Non-Lepidoptera are usually pinned straight out of alcohol, when they are flexible enough to handle. If they are collected and kept dry before preparation, then a relaxing chamber may be used to rehydrate them. After the pin is inserted, the specimen is placed on a Styrofoam board lined with white paper. Legs, antennae, and wings are arranged using brace pins that hold everything close to the body. Specimens remain on the board for about a week until they are fully dry.

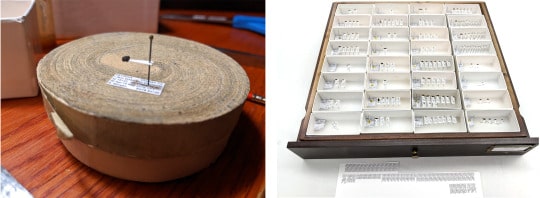

If specimens are too small to be pinned, they are mounted on paper points using shellac glue. The pin goes through the point made from archival paper using a tool known as a point punch. After laying the specimens with the underside facing up, the tip of the point gets a dab of glue and each specimen is glued on to the tip of the point.

Guess what the next step is…labeling!

As mentioned before, specimens tell an important story. The data is just as valuable as the specimens, and that data is printed on archival paper using a laser printer. A labeling block is used to apply the label on the pin, below the specimen. Any specimen that is prepared and labeled is ready to be identified and curated into the collection.

In a collection with 13.5 million specimens, space is valuable. Well prepared specimens take up less space and are less vulnerable to damage. A damaged specimen is still valuable because of the story it tells through its labels, even if damage makes the story incomplete. High-quality preparation is important because it allows for easier examination of the specimens and interpretation of the differences between species. These specimens are not just a bunch of bugs—all together, they are part of the record of life on Earth.

Vanessa Verdecia is Scientific Preparator in the museum’s Invertebrate Zoology Section. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.