Have you ever watched a film about archaeology and wondered how characters like Indiana Jones or Evelyn from The Mummy (1999) can run their fingers along a carved wall or slab, translating Egyptian hieroglyphs smoothly as they go?

The ability to read ancient Egyptian hieroglyphic writing today is all thanks to the Rosetta Stone. You may have heard of the Stone before, perhaps in the context of a popular language learning software, or you may know about the Stone itself, but do you know why it was such an incredible archaeological find?

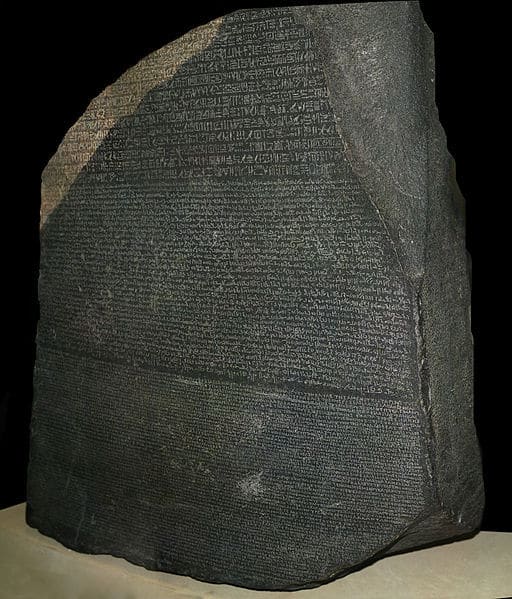

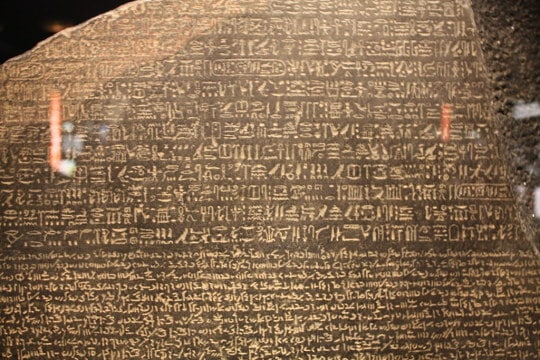

The Rosetta Stone is a black granodiorite (similar to granite) slab standing 4 feet tall, 2 ½ feet wide, and 11 inches thick. It is part of a larger stele, a stone or wooden slab erected to commemorate occasions, act as territorial markers, or for funerary purposes. The Stone bears three blocks of text written in three different languages- Egyptian hieroglyphs, Egyptian Demotic, and Ancient Greek.

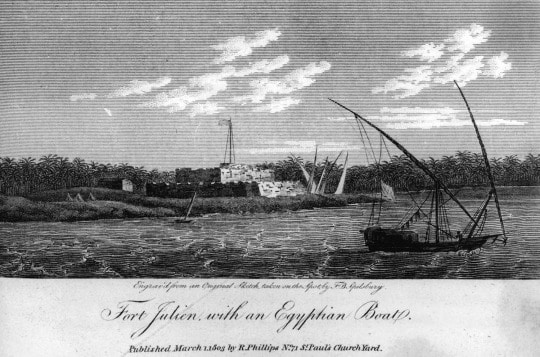

The Rosetta stone was carved during the Hellenistic period and moved at some later point. It was eventually used as construction material for a wall of Fort Julien in Rashid (or Rosetta). It was rediscovered there in 1799. While the history of its discovery is not particularly well-documented it is typically attributed to Pierre-Francis Bouchard, a French soldier on a Napoleonic campaign in Egypt. The Rosetta Stone was taken by British troops after they defeated France and transported to London. It has been on display at the British Museum since 1802.

The reason the Rosetta Stone is so significant is because it was the key that unlocked our understanding of ancient Egyptian hieroglyphs, giving us a window into the ancient civilization. The text on it is pretty mundane and of no great historical significance. It is a decree (called the Decree of Memphis), outlining the achievements and good leadership of King Ptolemy, who ruled Egypt from 204-181 B.C.E. The decree was made and copied onto several stelae which were placed in temples throughout Egypt, the Rosetta Stone being just one of them. Since the discovery and eventual translation of the Rosetta Stone, several other more intact stelae inscribed with the Decree of Memphis have been found.

Ancient Greek was already well known to scholars, so the translation of that section happened fairly quickly, though unknown religious and administrative jargon delayed the process. Hubert-Pascal Ameilhon published the first translation of the Greek text in 1803. Before the discovery of the Rosetta Stone, there had been little success in translating Demotic and even less in translating hieroglyphs. Having all three languages together was an incredible resource for scholars because for the first time, they could study whether there was a direct link between the languages, and use their translation of the Ancient Greek text to translate the other languages on the stone.

Swedish scholar Johan David Åkerblad had already been working on translating an unknown script found in Egypt. He called this script “cursive Coptic” though it did not share many similarities to Coptic, a language derived from the Greek alphabet and used in Egypt through the 17th century C.E. The language he was studying was actually Demotic, and the discovery of the Rosetta Stone aided his research. He, along with Antoine-Isaac Silvestre de Sacy, set to work translating this larger text. Having the Greek text side by side, they were able to locate where names lined up, and begin deciphering Demotic. Åkerblad proposed an alphabet of 29 letters, half of which were correct, but they failed to identify the remaining characters.

The translation of the hieroglyphic text similarly revolved around proper names. As early as 1761, scholars believed that characters enclosed in cartouches (or ovals with a line at one end) were proper names. By sorting through the Greek text and comparing where names would most likely be Thomas Young, foreign secretary of the Royal Society of London, was able to discover phonetic characters that aligned with Greek names. This discovery was incredibly important, as Young found these phonetic characters were similar to the Demotic characters in proper names, and then further discovered about 80 other similarities between Demotic and hieroglyphic writing. This shows that Demotic is actually a mix of phonetic characters and ideograms, which is what prevented Åkerblad and Silvestre de Sacy from progressing further with their translation, they had assumed Demotic used only phonetic characters.

In 1814, Young corresponded with Jean-François Champollion, a teacher at Grenoble who had done scholarly work on Ancient Egypt. Champollion was able to construct an alphabet of phonetic hieroglyphs, which was announced publicly on September 27th, 1822. From there, Champollion went on to develop an Ancient Egyptian grammar and hieroglyph dictionary, which was published after his death in 1832. Other scholars drew upon the work done by Åkerblad, Silvestre de Sacy, Young, and Champollion to delve deeper into the text on the Rosetta Stone and create a full translation.

Indiana Jones and the Raiders of the Lost Ark takes place more than 100 years after Champollion’s dictionary was published. We can assume that during his studies and explorations, Indy studied this dictionary, and any others that followed, giving him the ability to read Egyptian hieroglyphs at any moment. While Indiana Jones is a fictitious archaeologist and scholar, we have real scholars to thank for the fact that we can enjoy films about this character today!

Jo Tauber works in LifeLong Learning at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.