As someone who was born in 1998, I grew up in a world full of LED screens. With the click of a button, screens come to life and display anything and everything. The black mirror suddenly stops reflecting your anticipating face and a myriad of icons and a colorful image burn themselves into your retinas. I couldn’t imagine another way of consuming images. I’ve perused old photo albums with glossy, physical photos as a fun trip down memory lane with my parents, but digital images displayed on our computer desktop or our television screen was my first remembered experience of imagery. Holding a camera, clicking a button, and having the image still and lit up on the camera screen. How else could it be?

I’ve worked in the Carnegie Museum of Natural History for 3 years now in the Herpetology department, and it never ceases to amaze me. I’ve been fascinated by the beautiful specimens from all corners of the world, some of which can’t be found in nature anymore. Our Alcohol House is home to many preserved frogs, salamanders, snakes, and turtles that I have worked closely with and appreciated for their features and patterns. Seeing these creatures that I would have to travel across the world to see in real life is a treat every time I go to the museum.

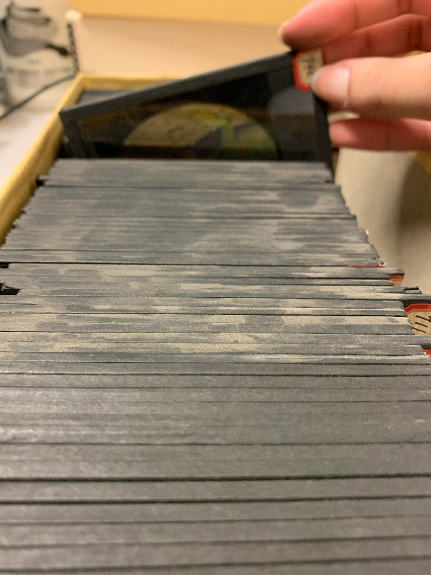

I recently moved from working on our physical preserved specimens to start a project of cataloging lantern slides that were used for presentations in the 1920s. We pulled out the boxes labeled Lantern Slides with numbers from 1- 1000. I opened it up, imagining vintage, unedited photographs with bright colors on glass. And instead it was filled with hundreds of dusty, sooty (Pittsburgh’s classic problem) rectangle slides stacked up in an unassuming row. I gingerly picked one up to see if I could see the image, and I could see a dull outline of a frog, nothing special, and less colorful and detailed than the preserved frogs I had seen from all corners of the world in the Alcohol House or the beautiful National Geographic photos I have seen online. Just a piece of dark glass with an outline of a frog. This…was going to be boring.

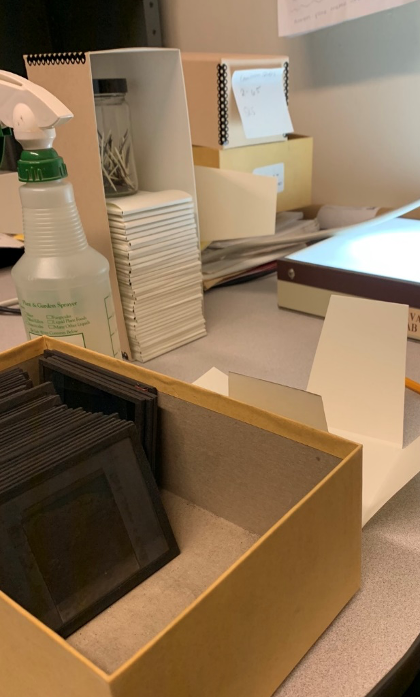

I sat down for my first day of going through the slides and set up my station for cleaning and recording the information on the slides. I saw that a new gadget had been added to my repertoire of conservation tools, a light box. I plugged it in and pressed the button–nothing. Sighing, I did the archaic press-and-hold, and the light slowly flickered on, creating a large rectangle of plain, white light. Buttons were meant to immediately turn something on and show me images, and this silly box not only required a press-and-hold but just showed me light! Dejectedly, I picked up the first lantern slide, number one, and looked at the dark image with the outline of a frog. I wiped off the black soot, and began to record the information, slide 1, photograph, frog… I wrapped it up to make sure that the glass and image wouldn’t get damaged and placed it into a new box. 999 more to go.

I went to pick up the next slide, when my eyes fell on the light box, which was currently acting as a glorified lamp. Should I make this task even more grueling by adding the extra step of placing the boring image on the boring light or should I just work through all of them as fast as possible and go back to handling our amazing specimens? I decided to take the extra step of placing the slide on the light box.

And suddenly, the image came to life.

The vague green with some dark splotches that was dull on the slide became the vibrant color I had imagined, and the details of the frog’s pattern were crisp and clear. The image had an almost 3D, life-like quality that the screen does not have the depth to convey. I was shocked that these dust covered glass rectangles were holding such secrets within them, and that all it took was placing them on a light box to unveil their beauty. Without immediate gratification, I had made up my mind that these images weren’t beautiful, when all I had to do was take a few extra steps to discover images unlike those that I had seen on screens. I proceeded to take the image off and watch it revert back to dull and lifeless, and place it back on to the light box and watch it come to life, and marvel at how these little glass slides went from boring to fascinating in a second.

Lantern slides felt like they were of the past, a time where image projecting and quality must have been worse—right? By working with these old, dusty slides, I was able to see images of reptiles and amphibians the likes of which I hadn’t seen before. I now relish every opportunity I have to go into the museum and look at salamanders, snakes, alligators, and a whole host of other creatures (and researchers) on the light box. The Carnegie Museum of Natural History is rich with resources from the past and working with the Herpetology Department has given me the opportunity to get an inside look into how the museum might have operated far before even my grandparents were born. Getting involved in helping out at the museum is a wonderful way to get involved in outreach, science communication, and is an overall enriching experience!

Swapna Subramanian is an Anthropology and Ecology & Evolution double major at the University of Pittsburgh, and a volunteer in the Section of Herpetology at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.