Blubber is a thick layer of fatty tissue under the skin of all cetaceans (whales and porpoises), pinnipeds (seals and walruses), sirenians (manatees), and polar bears. Blubber is the primary fat storage for animals that feed and breed in different parts of the ocean or in the Arctic. It’s kind of like how we dress up in layers before going outside to play in the snow. Want to test how it really works? Follow these simple instructions to make your own blubber glove!

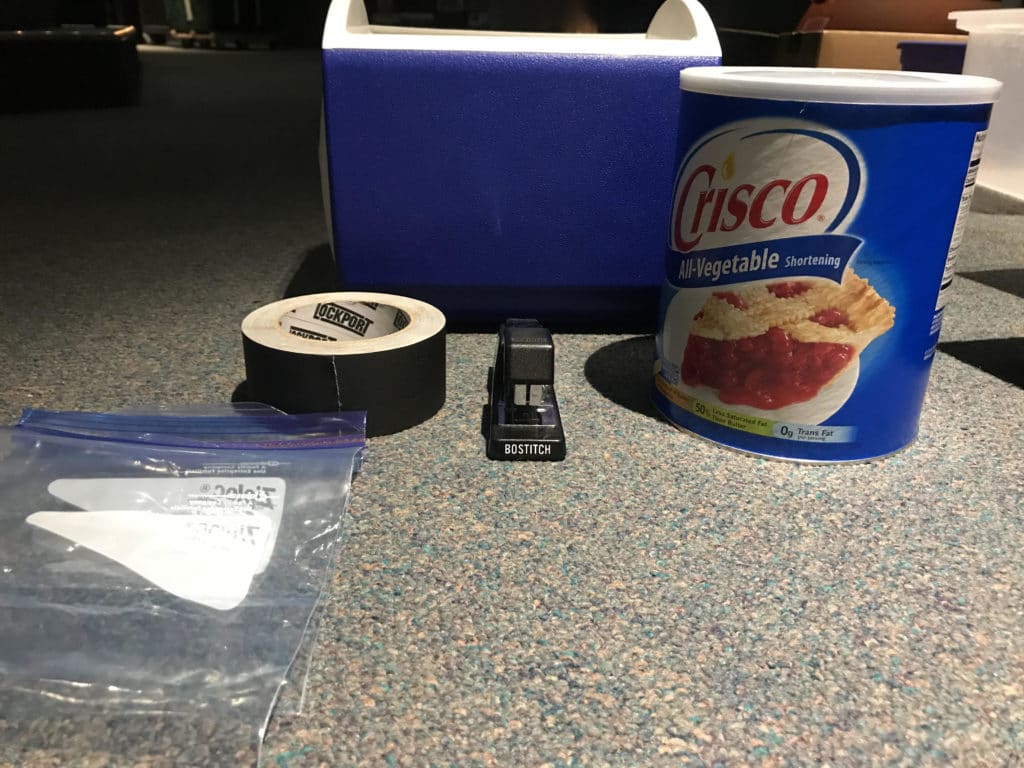

What You’ll Need

Directions

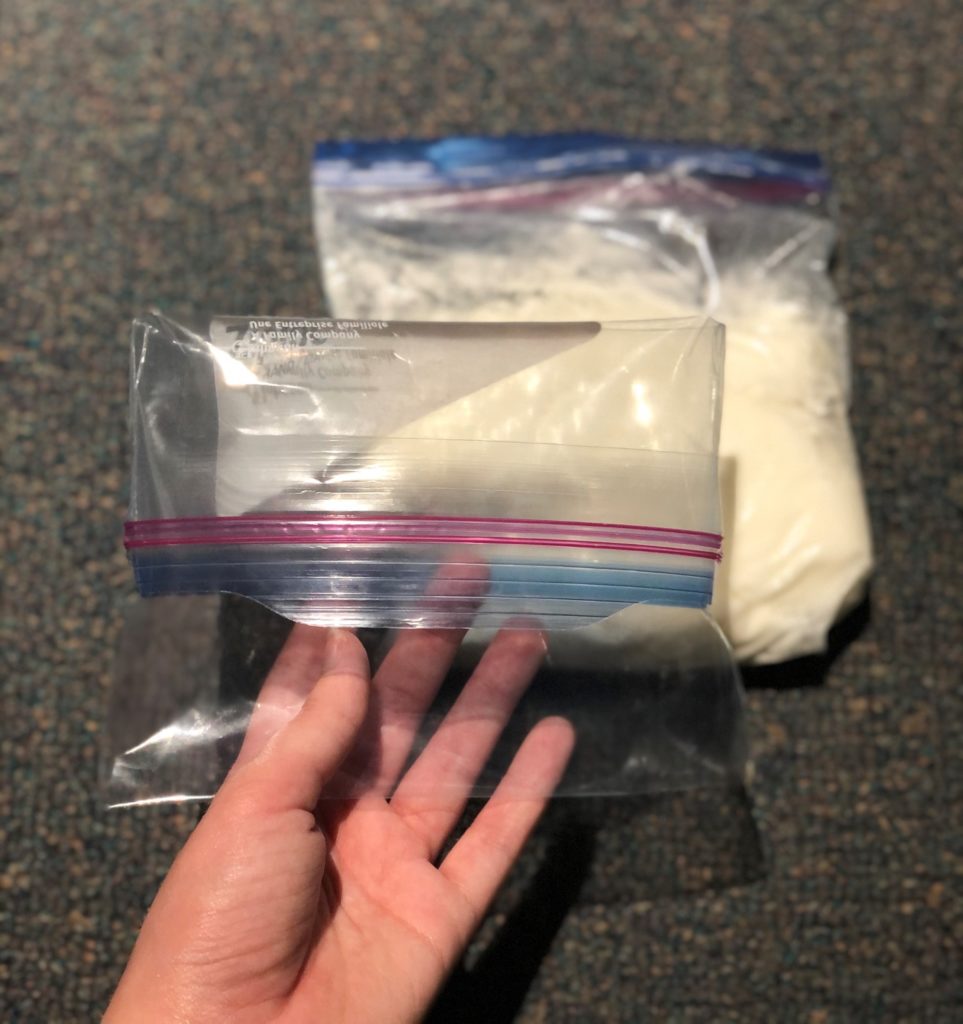

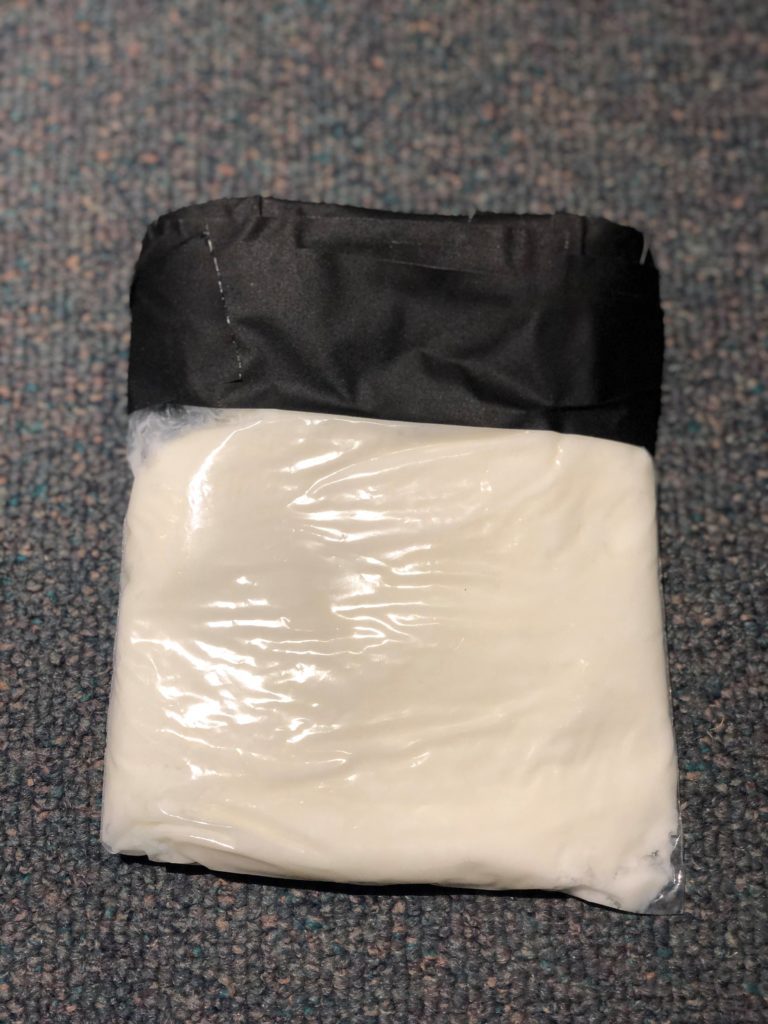

- Fill one ziplock with a generous amount of shortening (do not seal the bag).

- Place your hand inside the second, empty ziplock bag, and push it into the shortening-filled one.

- Using your hands, spread the shortening around the ziplock bag until the inner bag is mostly covered (try not to spill any shortening outside the bag or near the edges!).

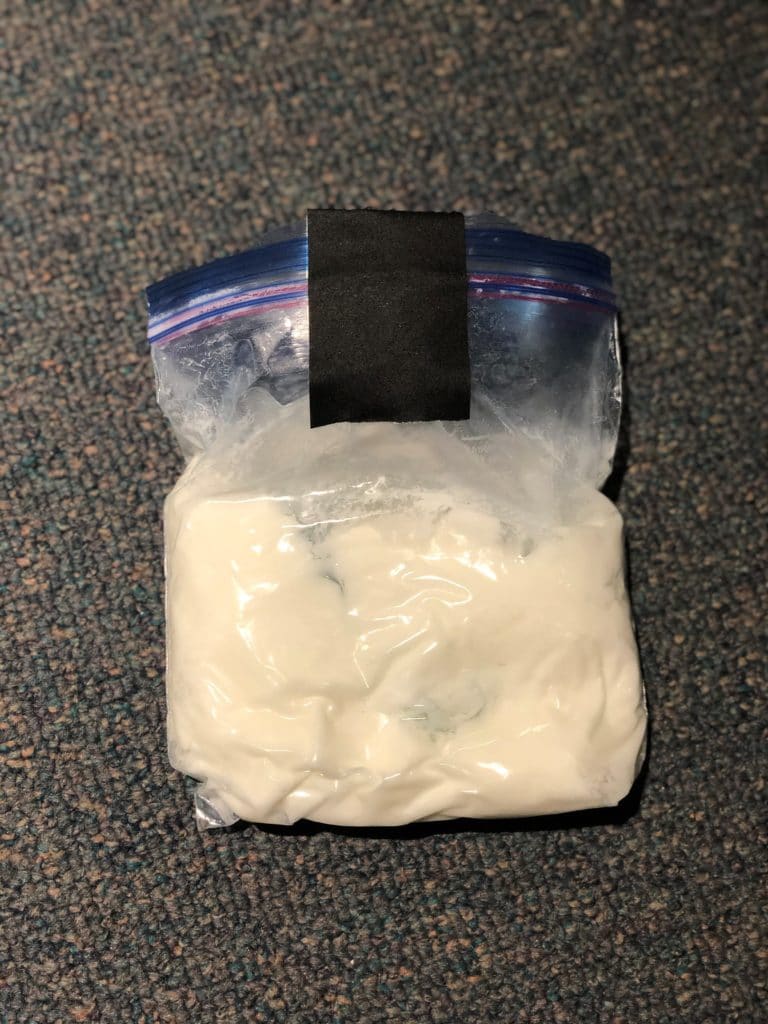

- Fold the top of the inner ziplock bag over the outer bag.

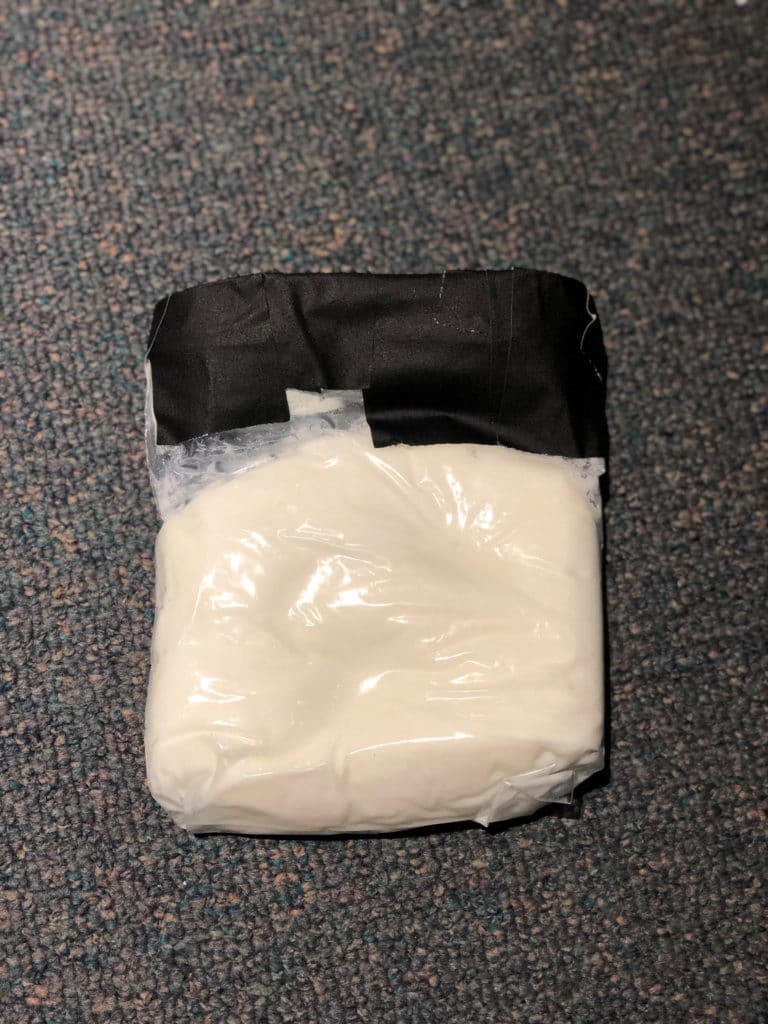

- Duct tape the fold to ensure the shortening will not overflow or leak out of the glove.

- OPTIONAL: for extra strength, staple the duct tape between the layers of duct tape. Use more duct tape to cover the staples to prevent injury.

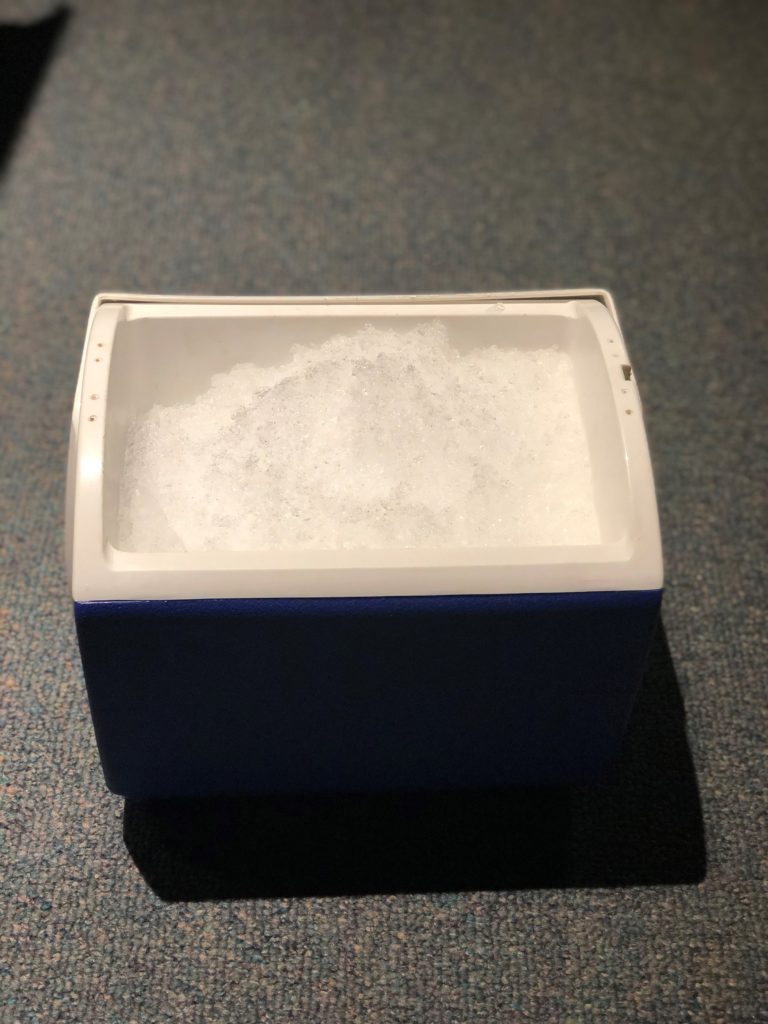

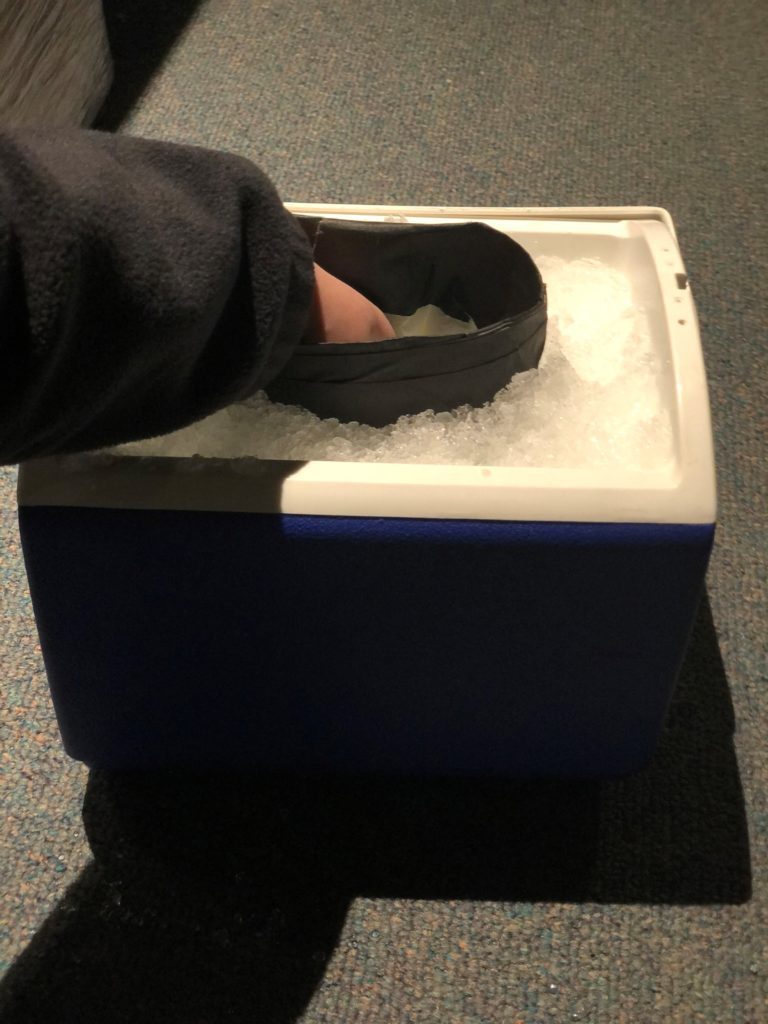

Now that your blubber glove is ready, dunk your hand with the glove into the bowl of ice water and see what happens!

- OPTIONAL: use a stopwatch to count how long it takes for your hand to feel any temperature change (don’t leave your hand in for too long!). Record your data.

- Record how cold the ice water is with a thermometer

What’s Happening?

Shortening, a type of fat that’s solid at room temperature, stores energy. While the shortening doesn’t have nearly the same amount of energy-storing capabilities as blubber, it does work in a similar way. Blubber’s primary functions include:

- Adding Buoyancy—this allows the animal to conserve energy while swimming and even float near the surface of the ocean to breathe during periods of rest.

- Providing extra insulation—this helps the animal survive harsh weather conditions and sudden temperature drops. In colder weather/water, the blood vessels in blubber constrict, decreasing the amount of blood flow and conserving heat.

- Storing energy—like the shortening, blubber stores energy, but is richer in proteins and a type of fat called lipids.

Many cultures rely on blubber, even today. Muktuk, thick slices of whale blubber and skin, is a traditional food consumed by some Innuit and First Peoples groups. Blubber is a vital food source in cold conditions, as it contains a high amount of vitamins D and C, which isn’t easy to come by in colder areas of the world. However, recent studies show blubber is susceptible to biomagnification—the process in which a foreign substance increases in level as it passes up the food chain. Toxins such as PCB, a chemical now known to cause cancer in humans, has been found in fish and animals that consume them. When these predators, often at the top of the food chain, consume fish with toxins in them, their blubber also becomes toxic. PCB is often hard to break down and doesn’t degrade over time.

For many animals, blubber is the key to their survival. The next time you go outside during a chilly winter day, make sure to wear layers to keep yourself warm, too!