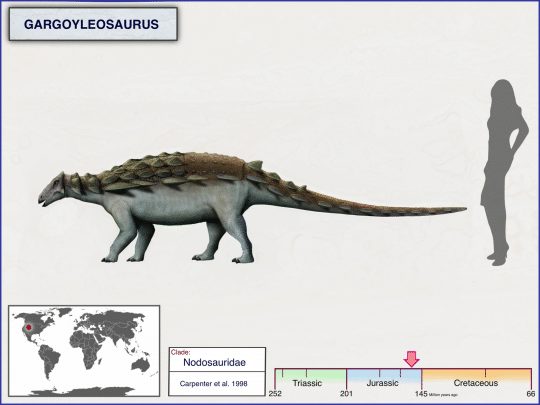

Do you know what you’re going to dress up as for Halloween? This year, I’ll be going to work dressed as Velma Dinkley from Scooby-Doo. For the October edition of Mesozoic Monthly, I’ll be ‘unmasking’ a dinosaur with a monstrous name: Gargoyleosaurus parkpinorum, an armored dinosaur from the Jurassic Period!

Gargoyleosaurus belongs to my favorite group of dinosaurs: the ankylosaurs! The group Ankylosauria is comprised of many big-bodied herbivores covered in osteoderms, which are pieces of bone embedded in the skin that act like armor. Their osteoderms came in many shapes and sizes, from tiny ossicles that protected their bellies, to large, fused pieces of bone that formed club-like structures on their tails. In most cases you can easily distinguish between the two major groups of ankylosaurs based on their style of osteoderms (though there are other features that distinguish them as well). Ankylosaurids are famous for their tail clubs: the last vertebrae in their tail overlap to form a rigid ‘handle’ that ends with a mass of fused osteoderms akin to a club. Nodosaurids, their sister group, sported massive osteoderm spikes on their shoulders instead of clubs on their tails. Some paleontologists distinguish a third group of ankylosaurs, called polacanthids, which have a rectangular ‘pelvic shield’ made of fused osteoderms that rests over the hips. There’s a lot of overlap between ‘nodosaurid’ and ‘polacanthid’ characteristics, though, so ankylosaurs with pelvic shields are typically grouped in with the nodosaurids instead of being recognized as their own group.

Conveniently, the Dinosaur Armor temporary exhibition at Carnegie Museum of Natural History features representatives of all three (or both, depending on your taxonomic preference!) ankylosaur subgroups: the ankylosaurid Akainacephalus, the nodosaurid Peloroplites, and the polacanthid (= nodosaurid?) Gastonia.

There’s been some debate over where to place Gargoyleosaurus on the ankylosaur family tree because it displays a range of features from both major groups. It has pointy, horn-like osteoderms on the back of its head, which is a feature of ankylosaurids, but its skeleton lacks evidence of a tail club or other ankylosaurid characteristics. It also has a long snout, shoulder spines, and a pelvic shield, all features of nodosaurid (or polacanthid) ankylosaurs. The best explanation for the mix of features seen in Gargoyleosaurus is that it was one of the most basal nodosaurids, meaning it was one of the earliest nodosaurids to evolve and is therefore located at the base of the group’s evolutionary tree. If Gargoyleosaurus was a basal nodosaurid, that would explain why it still had features similar to those of ankylosaurids: because it had only recently evolved from the common ancestor of ankylosaurids and nodosaurids, not enough time had elapsed for features of that common ancestor (such as ankylosaurid-like skull osteoderms) to be removed by natural selection. This would be in keeping with the status of Gargoyleosaurus as one of the geologically oldest ankylosaurs of any kind discovered to date.

No matter which ankylosaur subgroup Gargoyleosaurus belongs to, everyone can agree that it was a well-armored tank. Armor is a very useful defense against predators, since it generally covers the most vulnerable places on the body, such as the neck. Gargoyleosaurus lived in what is now the Morrison Formation, a famous set of rocks in the western US made of sediment deposited during the late Jurassic Period (the second of three periods in the Mesozoic Era, or Age of Dinosaurs). Most of the Jurassic dinosaurs on display at CMNH come from the Morrison Formation, such as our beloved long-necked sauropod Diplodocus, the even more massive sauropod Apatosaurus, and the forever popular Stegosaurus. But the Morrison ecosystem was home to a horde of formidable carnivores too—Allosaurus, Ceratosaurus, and Torvosaurus among them—so the armor of Gargoyleosaurus undoubtedly came in very handy. Contrary to what certain “Jurassic” franchises would lead you to believe, though, Tyrannosaurus rex did not live during the Jurassic Period, and so it never interacted with Gargoyleosaurus or any other members of the Morrison dinosaur community. That said, if trick-or-treating had been a possibility in the Jurassic, I’d imagine those inflatable T. rex Halloween costumes might have been very popular. Who doesn’t love those silly costumes?!

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: What is still unknown about “the chicken from Hell”?