January brings with it a new year and a new installment of Mesozoic Monthly! At the start of a new decade, perhaps the perfect prehistoric creature to honor this month is the dinosaur Ledumahadi mafube, the “giant thunderclap at dawn.”

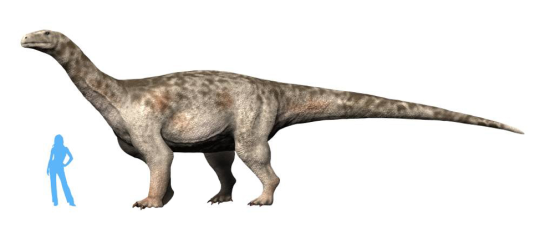

Ledumahadi was an early sauropodomorph, a group of herbivorous dinosaurs that ultimately produced the famous sauropods. Sauropods such as Brachiosaurus or Diplodocus are popular dinosaurs because of their often monstrous sizes, long necks, and lengthy, sometimes whip-like tails. One of the traits that paleontologists believe helped sauropods get so big was their pillar-like legs. Their legs were straight, like stilts, and heavily constructed so that they could support the weight of the animal. Modern elephants also have columnar legs, similar to those of sauropods, because this style of limb is so efficient for big animals. Non-sauropod sauropodomorphs tended to be smaller than their sauropod cousins, and could walk on either two legs or four. Quadrupedal early sauropodomorphs such as Ledumahadi did not have the columnar legs of sauropods, but instead walked with their forelimbs partially bent.

Life reconstruction of Ledumahadi by Nobu Tamura with a human silhouette for scale. This was a big beast! Note how, unlike its sauropod kin, this early sauropodomorph walked with its forelimbs flexed at the elbow. Read the 2018 scientific paper that described it (for free) here.

The largest known dinosaur of its kind, Ledumahadi weighed over 13 tons (12 metric tons), and reconstructions estimate that it grew over 30 feet (9 meters) long! This size is noteworthy, because it shows that it was possible for sauropodomorphs to reach gigantic sizes without columnar legs. This demonstrates that terrestrial animals can get big due to a variety of adaptations. In this case, the tremendous size of both sauropods and Ledumahadi is an example of convergent evolution, a process in which unrelated animals can evolve similar features. One classic example of convergent evolution is wings. Birds, bats, and pterosaurs are unrelated, yet all evolved similar structures that increase surface area for flying. But they all did it in different ways: birds have feathers anchored to the forearm and a fused hand, bats have skin stretched across five fingers, and pterosaurs had skin stretched along one long finger. Although we may not definitively know how Ledumahadi achieved its status as a “great thunderclap,” we do know that it did so along a different evolutionary pathway than its sauropod relatives.

The name Ledumahadi mafube means “great thunderclap at dawn,” referring to the massive size of the animal and its early place in the rock record. Unlike many dinosaur names, it is not derived from Latin or Greek; instead, it is from Southern Sotho, one of the languages spoken in South Africa, where the creature’s fossils were discovered.

Not many well-known animals lived in the Early Jurassic of southern Africa alongside Ledumahadi; the most famous dinosaurs are other sauropodomorphs such as Massospondylus, the small bipedal herbivores Heterodontosaurus and Lesothosaurus, and the small carnivore Coelophysis (formerly called Syntarsus) rhodesiensis. They all lived in an arid floodplain that was crisscrossed by meandering streams. Every so often, after a long period of stability, these water channels would flood, depositing new soil and nutrients and rejuvenating the ecosystem. A great deal of plant growth occurs after floodplains drain, reflecting a cycle of renewal that is familiar to us during each and every new year.

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.