Welcome back to Mesozoic Monthly! Spring has sprung, and you know what that means: baby animals are coming! It only makes sense that the star of this month’s post should be as small and cute as chicks or puppies. With a wingspan of less than 10 inches (25 centimeters), Nemicolopterus crypticus is one of the tiniest known pterosaurs – about the size of an American Robin!

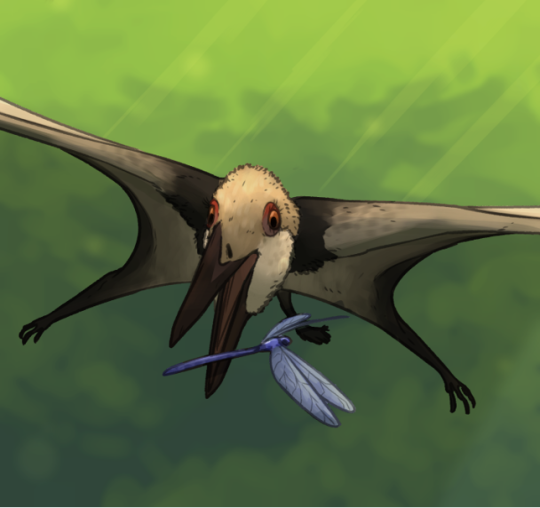

Life reconstruction of the adorable little pterosaur (flying reptile) Nemicolopterus crypticus by paleoartist Connor Ashbridge, used with permission. You can find Connor’s other work on Instagram @pantydraco.

Nemicolopterus is a pterosaur, a kind of prehistoric animal that is commonly called a “pterodactyl” or “flying dinosaur.” However, pterosaurs are not dinosaurs! Dinosaurs are all animals within a specific group of reptiles known as the Dinosauria. Pterosaurs comprise a separate group of reptiles that were specialized for flight, called the Pterosauria. These flying reptiles are extraordinary; they not only represent the earliest-known flying vertebrates (animals with backbones), but they also achieved flight in a different manner than did modern flying vertebrates (birds and bats)! Over half the length of a pterosaur’s wing was made up by a single super-long finger (specifically, the fourth finger, aka the ‘ring finger’ of a human) that anchored a broad skin membrane. It might seem like it’d be impossible to fly on just one finger, but many pterosaurs managed to grow to gargantuan sizes. Cousins of Nemicolopterus known as azhdarchids (one of which, Quetzalcoatlus, soars above T. rex in Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s Dinosaurs in Their Time exhibition) could reach estimated wingspans of 39 feet (12 meters). That’s as big as a small airplane!

Tiny, fuzzy, and adorable, Nemicolopterus would have looked a lot like a baby bird if you could take a trip back to the Cretaceous and see this pterosaur in the wild. In fact, the only specimen we have of Nemicolopterus may have been a baby! It’s often difficult to tell just based on its fossilized skeleton whether a prehistoric animal was fully mature or still in the process of growing and changing when it died. One way of telling if a fossil reflects an adult is whether certain bones have completely fused together (the technical term is coossified). You may know that humans have more separate bones as babies than we do as adults; this is because, as a person grows, certain bones like the ones that make up your skull fuse together along lines called sutures. Many baby bones also tend to be soft and flexible because they start out as cartilage, which is replaced by solid bone over time through a process called ossification. Several important bones in the Nemicolopterus fossil are ossified, so we can be sure that it was not a hatchling. However, since paleontologists agree that this specimen was still young when it died, and also that baby pterosaurs were precocial (i.e., able to effectively move about and find food on their own shortly after hatching), there’s still a significant chance that the Nemicolopterus fossil represents a young life stage of another, larger pterosaur.

There’s a good candidate for which pterosaur might be the adult form of Nemicolopterus, if indeed the only known fossil is just a baby of another species: Sinopterus is a tapejarid pterosaur that lived at the same time and place as the little fellow. Tapejarids are unique because they were likely arboreal and had beaks that appear useful for eating plants or fruit. Nemicolopterus crypticus was named the “hidden flying forest dweller” as an homage to the forested wetlands in which it lived roughly 120 million years ago, in what is now Liaoning Province in northeastern China. It spent its time in the trees, attempting to avoid predatory dinosaurs such as the famously bird-like dromaeosaurid Microraptor or the distant T. rex relative Sinotyrannus.

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.