Welcome to April! Have you seen any flowers blooming yet? Often, when we think of flowers, we also think of their pollinating buddies, the bees. However, bees are not the only pollinating insects around today, and the same was true during the Mesozoic Era (the ‘Age of Dinosaurs’). One interesting prehistoric pollinator is Sophogramma lii, a beautiful pollen-eating lacewing from the Cretaceous, the third and final time period of the Mesozoic.

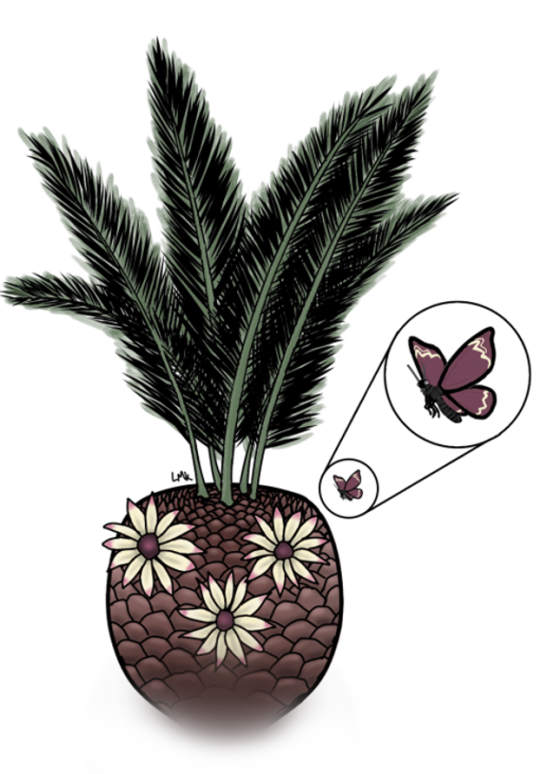

Sketch of Sophogramma lii alongside the Jurassic/Cretaceous seed plant Cycadeoidea by ginjaraptor on DeviantArt. Cycadeoidea was not a flowering plant, even though it looks like one; the flower-like structures are known as strobili and are actually types of cones!

Modern lacewings, for those who aren’t familiar, are a group of small flying insects with two pairs of wings of about equal size. They get their common name from the net-like pattern of veins on their wings. Most of today’s lacewings are predators that eat other small insects. Sophogramma, however, belongs to an extinct group of relatively large lacewings called the Kalligrammatidae, which were not predators but rather pollen eaters and juice drinkers. This group is commonly called the “butterflies of the Jurassic” due to several similarities with modern butterflies: their mouthparts formed long, tube-like siphons for drinking plant juices; their feeding habits resulted in the transference of pollen between plants; and their wings had scales and were distinctly patterned to ward off predators. Astoundingly, we know that kalligrammatids had patterned wings because these patterns are actually preserved in their fossils! Sophogramma lii had whimsical winding stripes along the edges of all four wings. Although we don’t know the exact color of the wings, we do know that these stripes were lighter in color than the rest of the wing. Other kalligrammatids had large eyespots adorning their wings, like many butterflies today.

Beautifully preserved fossil of Sophogramma lii clearly showing the light-colored wavy stripes along the edges of its wings. Image from a research paper by Yang et al. (2014).

The plants that Sophogramma snacked on (and incidentally, pollinated) almost certainly lacked flowers. Flowering plants, technically called angiosperms, didn’t evolve until early in the Cretaceous, roughly 130 million years ago, but kalligrammatids had been around since at least the middle part of the preceding Jurassic Period, about 160 million years ago. So what plants were kalligrammatids eating for all that time? And why did these insects die out just as angiosperms were becoming common? Well, kalligrammatids’ host plants probably consisted of spore-bearing vascular plants such as ferns and non-flowering seed plants including conifers, cycads, ginkgos, and a variety of extinct forms. Before angiosperms burst onto the scene, these types of plants dominated land ecosystems. Despite lacking flowers, these plants would still have used spores and pollen to reproduce, providing kalligrammatids with plenty of food. Once angiosperms evolved their flowers, these plants rapidly diversified and presumably outcompeted the host plants that kalligrammatids such as Sophogramma would have relied upon.

With a wingspan of six inches (15.3 cm), Sophogramma lii was a relatively large insect. Its fossils have been found in the Yixian Formation, an Early Cretaceous-aged rock unit that crops out in northeastern China. The Yixian represents a forested environment that many dinosaurs, archaic birds, pterosaurs, and other hungry critters called home. The distinctive stripes of Sophogramma likely helped it survive attacks by drawing these predators’ attention to its relatively ‘expendable’ wingtips instead of vital parts such as the head or body. I wouldn’t personally be inclined to eat one of these ancient lacewings, but with so many of those polarizing Peeps® on the shelves at this time of year, I think some people might actually prefer a seasonal Sophogramma snack!

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.