Happy Valentine’s Day from two cuddly Thrinaxodon, a close relative of mammals from the early days of the Age of Dinosaurs. The pose of the two Thrinaxodon is based on a real fossil. Art by ginjaraptor on DeviantArt.

Ah, February. It’s a time when love is on our minds, whether we are sharing our love with a romantic partner or with friends and family. For this edition of Mesozoic Monthly, prepare to fall in love with the adorable Thrinaxodon liorhinus, a little mammal relative that appreciated a good cuddle!

The Mesozoic Era (after which this blog series is named) is often known as the Age of Dinosaurs. After dinosaurs (except their descendants, birds), pterosaurs, and many other large reptiles became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous Period, a new era began: the Cenozoic Era, also known as the Age of Mammals. While mammals certainly became more prominent in ecosystems around the planet during the Cenozoic, mammals actually evolved during the Mesozoic alongside the dinosaurs. Mammals are the only survivors of a group of animals called cynodonts, which were warm-blooded (endothermic) creatures with specialized teeth and simplified lower jaws. Paleontologists are not yet sure if early cynodonts had evolved fur, one of the hallmark traits of mammals, but it is quite possible that critters such as Thrinaxodon had furry little bodies! Small pits that dot the snout of this cynodont suggest that it sported sensitive whiskers, which supports the hypothesis that it had a form of hair.

Whiskers are very sensitive to touch, making them useful for navigating the dark burrows that Thrinaxodonlived in. Many specimens have been found fossilized in their burrows as they slept, sometimes even in groups! A remarkably cute fossil preserves two juveniles curled around each other with their heads pressed close together in an eternal cuddle. It’s easy to imagine this as a case of young star-crossed lovers who died together, but it is just as likely that these two individuals were siblings sharing the same small burrow. Due to the number of fossils of mixed-aged groups of adults with younger individuals, paleontologists believe that Thrinaxodon parents provided some form of childcare before their offspring grew up and ‘flew the nest.’ Regardless of whether Thrinaxodon experienced romantic or familial love, it certainly gives us warm-and-fuzzy feelings today!

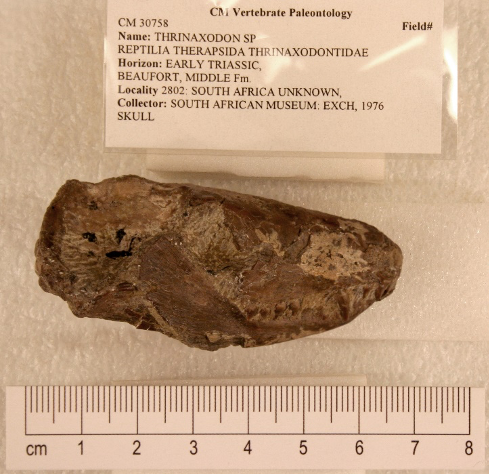

Carnegie Museum of Natural History has a couple Thrinaxodon fossils that we got from the South African Museum in the 1970s. Here’s one of them—our nice skull CM 30758—viewed from the left and right sides. Photos by Andrew McAfee.

Other Thrinaxodon weren’t the only animals that visited their cozy burrows. One noteworthy fossil shows a Thrinaxodon sharing its home with a small amphibian called Broomistega, which apparently took shelter in the burrow after being injured by a larger carnivore. Although Thrinaxodon was itself a carnivore, the bite marks on the Broomistega do not match up with the jaws of its roommate. Instead, Thrinaxodon probably ate little reptiles or other small vertebrates that roamed the Early Triassic of South Africa. Some of its above-ground neighbors included the large, predacious reptile Proterosuchus and the odd-looking dicynodont (distant mammal relative) Lystrosaurus. Fortunately or unfortunately, dinosaurs did not evolve until at least a few million years after Thrinaxodon became extinct. A prehistoric animal’s relationship with dinosaurs is not what makes it endearing, of course; Thrinaxodon is proof of that, since it has managed to steal our hearts all on its own!

Lindsay Kastroll is a volunteer and paleontology student working in the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.