In the same way scientists discover new plant or animal species, new minerals are usually found by exploring new places with hard work and determination, but also sometimes by pure chance and luck. In fact, you do not need to be a scientist to make exciting discoveries. You do need, however, to follow the basic steps of the scientific method when doing any research: (1) first ask a question you are interested in; (2) research that question; (3) develop a hypothesis; (4) test it; (5) analyze the data your tests generate; (6) draw conclusions; (7) and communicate the results.

When describing a new mineral, mineralogists like me gather a slew of analytical data about the atomic arrangement, chemical makeup, and optical and physical properties to completely characterize the mineral. The data we gather is recorded and accessible, so that when others find similar crystals the analytical data for those specimens can be compared. Allowing your findings to be further tested and improved, or even shown to be wrong, forms the foundation of all fields of science and medicine.

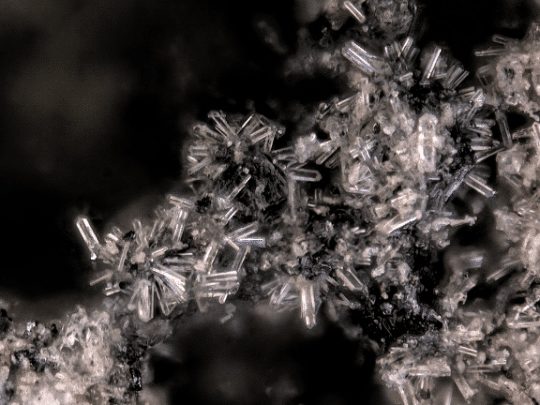

I recently gathered analytical data for the new mineral hydroxylpyromorphite, a mineral with a mouthful for a name, but one that is extremely important to removing toxic lead from drinking water. Hydroxylpyromorphite is a lead phosphate mineral, and part of a larger group of minerals with related crystal structures (the arrangements of atoms) called the apatite group. Our bones and teeth are made of apatite, calcium phosphate, and the natural processes that move this critical building block throughout our bodies are disrupted when exposed to lead, potentially causing brain damage and other diseases. Lead is especially dangerous to children, and to prevent lead poisoning, water treatment plants often add phosphate to the water supply. Under the right conditions, phosphate grabs strongly onto lead atoms, forming hydroxylpyromorphite and removing it from the water. Until our description, the crystal structure of this mineral was unknown. Now that we understand the crystal structure, the information can be used by others to develop better techniques or processes that reduce lead in drinking water.

Travis Olds is Assistant Curator of Minerals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences working at the museum.