by Linsly Church

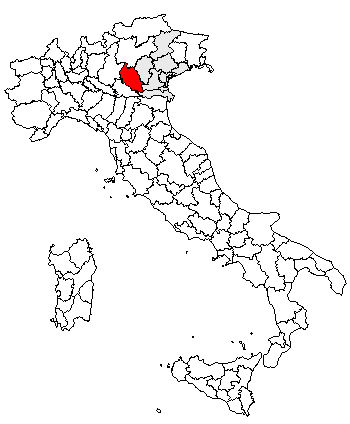

In 1903, Carnegie Museum of Natural History purchased an enormous private fossil collection from the Baron Ernest de Bayet of Brussels, Belgium. Over a 40-year period the Baron had amassed a collection comprising tens of thousands of individual fossils. At age 65 he married a much younger woman and sold the collection to fulfill her dream of having a house on the shore of Italy’s Lake Como. Within the collection are fossils from all over Europe. Fossils from Italy include the Monte Bolca fish collection, which contains about 290 beautifully-preserved specimens that date to about 50 to 49 million years ago, early in the Eocene Epoch.

One quarry at Monte Bolca has been owned by the same family for almost 400 years. It is known as the Pesciara, meaning the fishbowl, because many of the marine fossils found there are those of fishes. Because the preservation is so good in some layers of limestone, the site is considered a Lagerstätte. A Lagerstätte is a site that contains exquisitely-preserved fossils, typically representing a diversity of organisms. At Monte Bolca, some fishes and other creatures have preserved internal organs and even skin pigmentation, the result of an anoxic (oxygen-poor) environment that hindered decay and scavenging. The fossil site also differs from most others in that it is an underground mine with tunnels instead of a typical open quarry.

Carnegie Museum of Natural History’s collection of fishes from Monte Bolca is currently undergoing conservation. In the past, the museum’s Vertebrate Paleontology collection was housed on open shelves in rooms with poor air filtration systems, resulting in soot from the local steel industry building up on the fossils. In recent years, the museum has installed an HVAC system in the Vertebrate Paleontology collection rooms, which has greatly reduced the particulates that make it into these rooms and onto the specimens. In the years since these measures were taken, we in Vertebrate Paleontology have commenced a general cleaning of our specimens, starting with our fishes from Monte Bolca.

To clean the specimens, we use a soot sponge (or chemical sponge), which is also used by restoration companies to clean after fires. “Chemical sponge” is a slightly misleading name because there are no chemicals added to the sponge. It is made of vulcanized rubber and has tiny pores on its surface that collect fine soot particles without depositing chemicals on the fossil. Therefore, there is no need for water or additional solvents when using these sponges. Wet cleaning of soot can cause staining on the surface that is being cleaned so it is very important to use dry cleaning methods such as chemical sponges. In some cases, the soot on the specimens is so dense that it is obvious where cleaning has taken place.

Once the specimens have been cleaned, repairs are made as needed and labels are reattached if they are delaminating from (or falling off of) the specimen. Then, storage mounts are created for specimens as needed using archival materials. These materials are made specifically to be as neutral or inert as possible so as not to give off gases that could react harmfully with the specimens. Storage mounts are important because they reduce the amount of times someone needs to touch the specimen—which, in turn, reduces breakage—and protect the specimen from vibration when the compactors in which it is housed are opened and closed. These measures will help to protect the integrity of the specimens for years to come.

Linsly Church is the curatorial assistant for the Section of Vertebrate Paleontology at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Early Bats: Ancient Origins of a Halloween Icon

Meet the Mysterious Mr. Ernest Bayet

Sharing Shipping Space with Amphibians and Reptiles

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Church, LinslyPublication date: January 17, 2019