by Georgia Feild

Carnegie Museum of Natural History has always been a prized resource of knowledge, inspiration, and support for me. From visiting at age six to gaze at dinosaurs while holding my father’s hand, to sketching dinosaurs and mammals as part of Carnegie Mellon University art courses, and researching anthropological collections for college assignments and volunteer historical work, I have always found a home at this museum. When traveling and working around the globe, I realized the only places I wished to relax my mind and body were at Carnegie Museum of Natural History or in the woods.

Retiring at age 55 from a systems design engineering career left me with the time and opportunity to pursue my passions. I started birdwatching after a thirty-year hiatus, and as a result of that activity, 12 years ago I converted my mother’s yard into a five-star Audubon Bird Habitat. While involved with those activities, nature reminded me of the most basic mechanical rule: when a part is missing or broken the entire mechanism will stop working efficiently. Seeking more information about missing “parts” of our ecosystem brought me to employment and volunteer work at the museum.

While performing educational work at the museum, I realized how instilling knowledge and developing respect for all organisms is vital for our planet’s welfare. Through millennia, Indigenous People’s relationships with the places they lived have improved, conserved, and respected the natural world. For thousands of years people have understood how their existence depends on the environment. Because I wanted to learn more about traditional cultural conservation of ecosystems, about eight years ago I began volunteering at the Edward O’Neal Research Center (Annex) for the Anthropology and Archaeology Department.

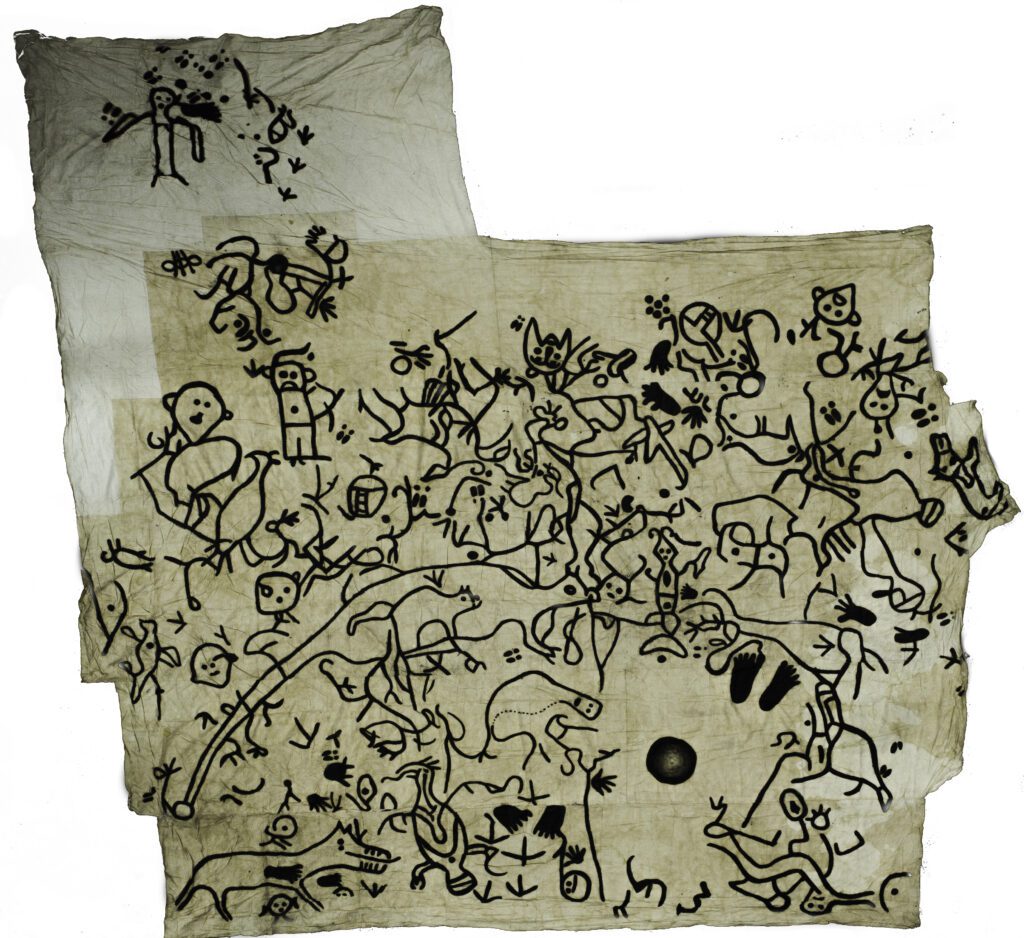

My volunteer work introduced me to cultures and traditions I never imagined. This growing awareness led to concentration on human relationships with animals, specifically birds. I was thrilled to discover how deeply people of Paleo (20,000 to 9,000 years ago) and Archaic (8,500 to 1,000 years ago) periods appreciated birds. Across many cultures, artifacts within the museum’ Anthropology and Archaeology collection feature depictions of birds.

As a volunteer, my most fascinating learning experience involves the massive Carnegie Museum collection of Western Pennsylvania petroglyph research documents. Digging through numerous file cabinets at the Annex containing petroglyph research from 1950 to 1979, I uncovered depictions of bird species that may still be found in the same areas today. Having traversed many a creek and stream bed attempting to take the “perfect” photo of egrets, herons, warblers, ravens, and ducks, I realized people in the past also wished to capture images of birds! Many petroglyph images carved into stone thousands of years ago resemble bird species currently found in the southwestern corner of the state.

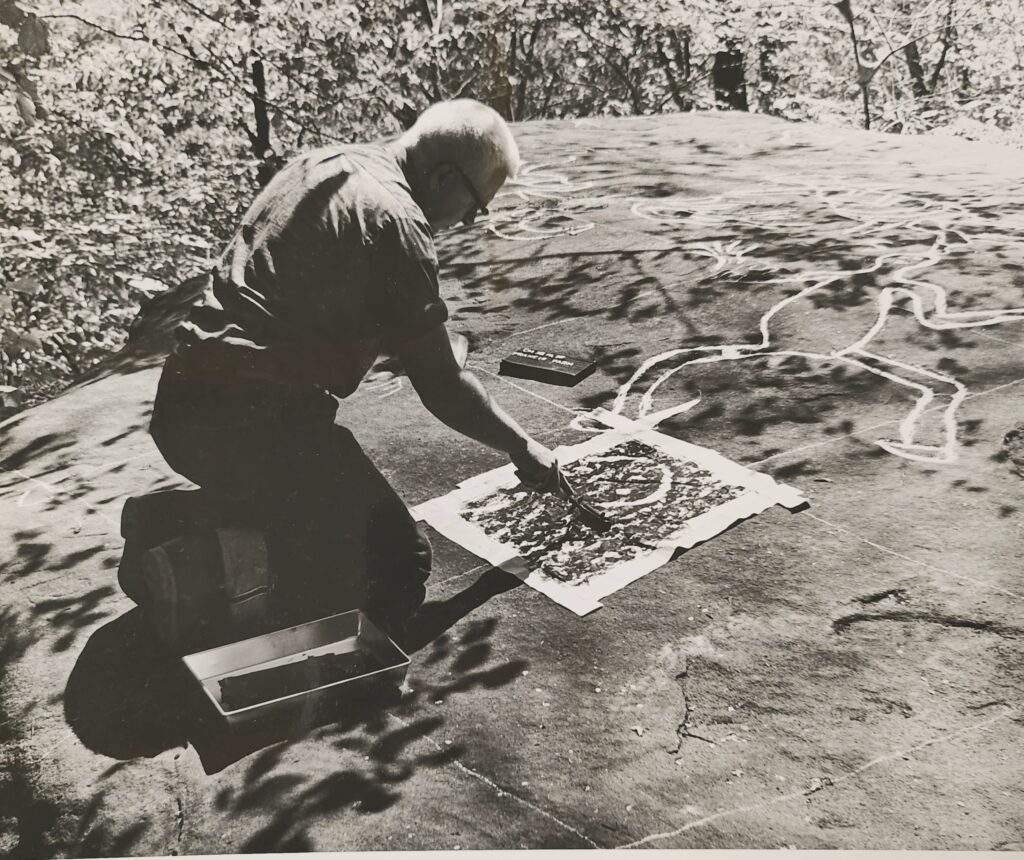

Petroglyph research started in the upper Ohio River Valley in 1900. At the turn of the 20th Century photography was incapable of accurately capturing rock carvings, leading early petroglyph researchers to chalk outlines of petroglyphs. Today chalk is no longer used because it is thought to be detrimental to the preservation of these important artifacts. Fortunately, photographic technology has progressed over 123 years so these artifacts may be recorded in a less invasive manner.

Between 1950 and 1979, over one hundred Paleo and Archaic sites in Western Pennsylvania were researched by 26 Carnegie Museum Archaeologists and Anthropologists. Petroglyphs were discovered at several sites, unfortunately some were later lost to dam, road, and channel construction. For example, a site known as the Midland Petroglyph was destroyed in 1910 when Ohio River channels were cleared and deepened for navigation and flood control. The Midland petroglyph was discovered in 1908-9 and thought to represent “power symbols” of the Midewiwin. Unfortunately, we cannot assess that petroglyph now to re-examine the ancient work with modern research technology and re-interpret its symbols in light of current archaeological research data. At other sites, Pennsylvania petroglyphs are being eroded by natural elements, making it important to revisit rock art sites before they are lost forever.

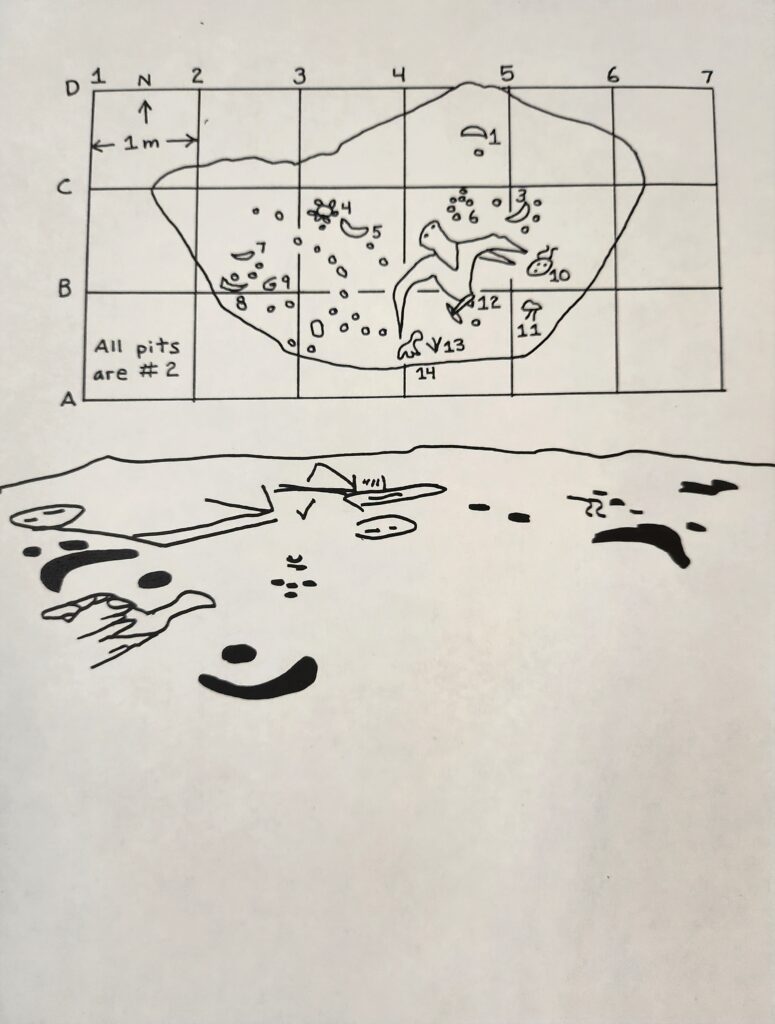

The Society of Pennsylvania Archaeology has currently taken an interest in revisiting some of the still accessible petroglyph sites. Using James L. Swauger’s research on the upper Ohio River watershed, (with records located at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History, and referenced in “Rock Art of the Upper Ohio Valley,” a 1974 publication), archaeologists are planning to revisit petroglyphs and update Swauger’s documentation of each site.

The Western Pennsylvania Native American Rock Art Survey, which was launched in November 2022, will record new documentation in Pennsylvania State Museum site database. The project is directed by Carnegie Museum Research Associates Ken Burkett and Brian Fritz, who will develop standards for eligibility of rock art sites for inclusion in the National Register of Historic Places.

It will be exciting to learn what scientists discover when revisiting these petroglyph sites. Questions, including when were these petroglyphs carved, why, and by whom all yearn for more informed answers. The locations of petroglyphs, their designs, and patterns within designs may lead to a better understanding of cultures that lived in Pennsylvania a very long time ago. Cultures survive by utilizing their distinct habitats. Although bird and animal representations may never fully explain the significance of a species to a culture, such images do tell us what animals were present throughout history.

Georgia Feild is a museum educator, Natural History Interpreter, and volunteer for the Archaeology/Anthropology Collections at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Related Content

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Feild, GeorgiaPublication date: May 5, 2023