Amber is fossilized tree resin, hardened over time into a natural plastic. Many people know of amber from the film Jurassic Park, in which scientists extract DNA from blood of dinosaurs that had been bitten by insects that were then entombed in amber. Sadly, however, DNA of non-avian dinosaurs (i.e., all dinosaurs except their descendants, birds) has never been successfully extracted from amber or any other fossil.

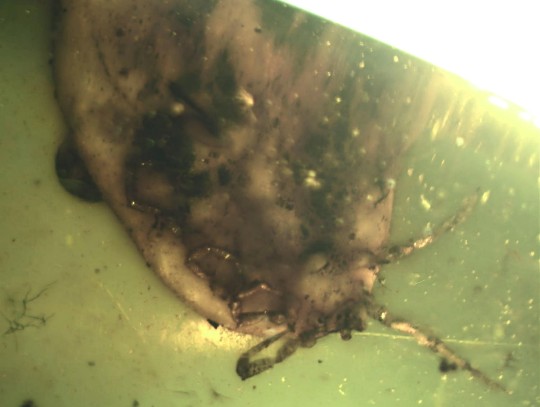

Nevertheless, exciting new discoveries from the Southeast Asian nation of Myanmar (formerly Burma) may bring us one small step closer to someday making Jurassic Park a reality. In a study that appeared today in the prestigious scientific journal Nature Communications, a team led by Enrique Peñalver of the Instituto Geológico y Minero de España in Madrid, Spain described ticks encased in Burmese amber from the middle Cretaceous Period, roughly 100 million years ago, including several specimens of a new tick species named Deinocroton draculi, or “Dracula’s terrible tick.” One of these ticks is engorged by blood, its volume about eight times greater than that of the non-engorged ticks. Furthermore, specialized hairs of skin beetle larvae—which commonly feed on tough organic matter such as skin, hair, or feathers in nests—are attached to the legs of two

Deinocroton ticks. This suggests that these ticks fed on feathered dinosaurs!

Whether the newly-described fossil tick specimens contain traces of dinosaur blood is something that future analyses might tackle. Some of these Deinocroton ticks, including the blood-engorged specimen, have been donated to Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH) by one of the study’s coauthors, Pittsburgh-area geologist and amber collector Scott Anderson. The fossils have been formally incorporated into CMNH’s Invertebrate Paleontology collection and will eventually be put on public display.

Photo credit: Scott Anderson.

Photo credit: Scott Anderson.