I met Kaylin Martin, a curatorial assistant for the Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH), at an internship fair when I was a transplant to Pittsburgh in September 2018. I was immediately drawn to her booth because it was made up of the most alluringly macabre set of oddities. The table was comprised of floating, translucent creatures in glass jars that I would come to know had been preserved in alcohol. In addition to the slick, scaly bodies of reptiles, there were vibrantly colored feathers of birds and their delicate skeletons splayed out on the white linen cloth of the booth. I thought then what I know to be true in an even greater sense now: that each was like a tiny work of art which had once been alive.

My background is in photography, which I studied at NYU before transferring to Pitt to major in the broader subject of digital media. I got the sense that CMNH was looking for interns with more of a scientific bent to their interests and education, but I was persistent about working in the alcohol house because I felt that there is an element of romanticism in going to great lengths to preserve such small lives. This appealed to me as my main interest has always been in portraiture. I felt like this could be a new kind of portraiture and the next step for me in my creative endeavors.

That fall I learned that the sum total of specimens of a particular type at a natural history museum is called a collection, in the same way that the Carnegie Museum of Art has its impressionist or modernist collections, for example. The Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at CMNH has the 10th largest such collection in North America, making it no small task for Stephen Rogers, the collections manager, to keep up with the care and preservation of each specimen.

Since starting as a photographic intern last year, I have photographed over 300 specimens (a fraction of the more than 230,000 specimens) from this collection as part of an ongoing project to digitize and upload images of paratypes to iDigBio.org. Mainly I work with tiny salamanders, some no larger than my fingernails, as many of the snakes were photographed the summer before I arrived. Sometimes Kaylin comes to me with special requests she’s received from researchers, which can be for photos of anything in the alcohol house, from frogs, to skinks, to snakes. In fact, some photos I shot of one such request were of a holotype (the individual from which a species is described) and will be published in Annals of Carnegie Museum this year.

After hours spent inspecting these creatures up close, I’ve come to recognize undeniably human qualities in them. In particular, the salamanders’ feet at the lower half of their bodies, which remind me of human hands. At times I remember that they are our distant ancestors and feel slightly ashamed that I barely thought of them or the well-being of the ones still living before my time at CMNH. It’s what I like best about being able to spend my time at the museum: that you never know what you might learn but also what you might remember. Facts you may have read or retained from school take on new meaning when you’re able to see evidence of them up close.

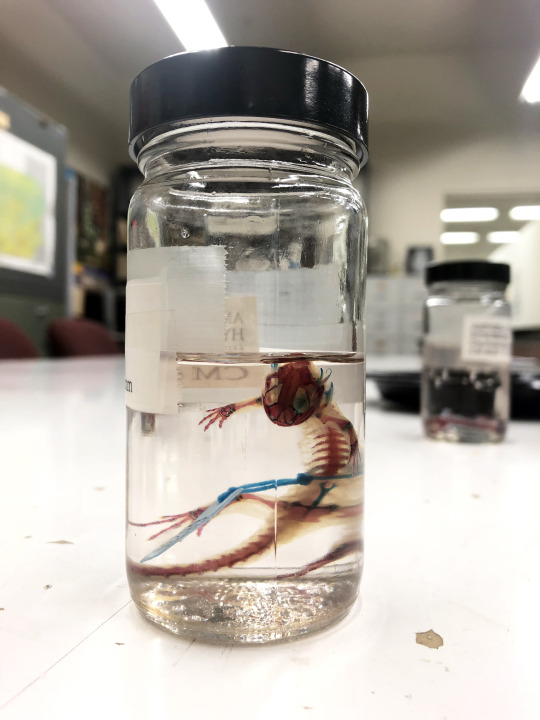

Just the other day in the CMNH offices, I saw a specimen that had been “cleared and stained.” After inquiring about it, I learned that this is a very old technique in anatomy, a process by which the specimen is chemically treated to render it transparent and stain its nervous system different colors. While the resulting specimen is useful for scientific research, it is also strikingly beautiful. I thought while looking at this strangely beautiful and arresting object that it wholly encapsulated my realization that scientists are more like artists than most people expect. For instance, both are inclined to ask the larger and more difficult questions of our existence such as: what is life? what happens after it? where did we come from? and what will we leave behind?

The researchers at CMNH are largely responsible for investigating and attempting to answer such questions. Jennifer Sheridan, assistant curator of Amphibians and Reptiles at CMNH, is specifically concerned with how climate change and human actions are affecting these indispensable species. If you are an inquisitive person who appreciates natural beauty and finds yourself motivated to preserve it then I encourage you to volunteer your time and talents to learn and work alongside the herpetology team at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History.

Rosemary Bencher is a work-study student in Amphibians and Reptiles. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.