by Patrick McShea

Where timber rattlesnakes are concerned, the scientific collections at Carnegie Museum of Natural History have more specimens than any other museum in the world. Of the more than 207,000 preserved amphibian and reptile specimens in the Section of Herpetology, 595 are Crotalus horridus, the scientific name for the timber rattlesnake. (In second place, with 507 specimens, is the North Carolina Museum of Natural Sciences. The Smithsonian and all other museums have far fewer specimens.)

For anyone wondering about the importance such unusual sets, collection manager Steve Rogers cites visiting researcher John Allsteadt, lead author of a 2006 scientific paper titled, Geographic variation in the morphology of Crotalus horridus.

“He examined and measured every one of our timber rattlesnakes. It was a whole lot of work,” Rogers said.

On the exhibit front, a newly restored historic diorama features three timber rattlesnakes collected more than a century ago near Ohiopyle, Pennsylvania. Alive, the venomous reptiles must have sometimes basked on sandstone ledges above the roar of Youghiogheny River rapids. In their current location, on the first floor near the Grand Staircase, polished marble is the predominant rock. Ambient sounds here range from the full-voiced chatter of visiting school groups to the electronic “ding” of adjacent elevator doors.

The contrast in backgrounds mirrors a longstanding gap between timber rattlesnake myth and reality. For the European immigrants who settled eastern North America, fear of timber rattlesnakes trumped any possible understanding of the species’ predictable behaviors, ecological role, and generally non-aggressive nature.

In the 1782 publication, Letters from an American Farmer, a work widely recognized as a foundation of American literature, author J. Hector St. John Crevecoeur summarizes the reptile’s predicament in the growing new nation:

“In the thick settlements, they are now become very scarce; for wherever they are met with, open war is declared against them; so that in a few years there will be none left but on our mountains.”

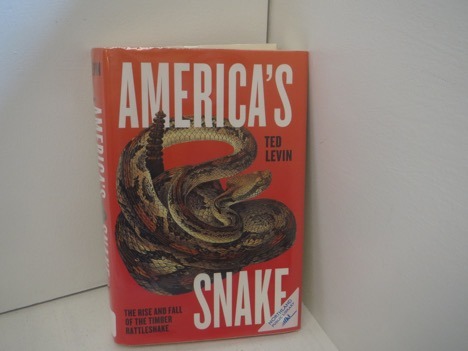

Readers interested in how this prediction played out over the intervening 23 decades should seek out America’s Snake: The Rise and Fall of the Timber Rattlesnake, a book by naturalist Ted Levin published in 2016 by The University of Chicago Press. The “open war” mentioned by Crevecoeur is an on-going theme in the work’s 481 pages, as is a threat unimaginable in colonial times, illegal international trade in venomous snakes. Levin also offers profiles of people working to safeguard the species and clearly relates what is currently known about timber rattlesnake evolution and anatomy, with attention paid to the physical adaptations that enable the creatures to make, store, and deliver a powerful venom composed of multiple toxins.

The bibliography of America’s Snake includes a reference to the publication of the researcher who measured all 595 Carnegie timber rattlesnakes. The note is an important if indirect link between this museum and a masterful modern work of natural history literature.

Patrick McShea works in the Education and Visitor Experience department of Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences of working at the museum.