Our modern furry friends aren’t the only animals that have endured the invasive bites of ticks. As it turns out, the pests may have fed on feathered dinosaurs, too—and now, we have the evidence in amber tick fossils.

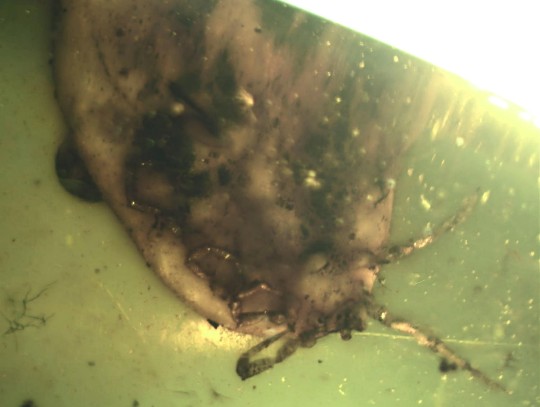

Carnegie Museum of Natural History is excited to receive some prehistoric Deinocroton draculi (“Dracula’s terrible tick”) specimens—including one engorged in blood, which researchers may identify as a dinosaur’s. Albert Kollar, invertebrate paleontologist and collection manager in the Section of Invertebrate Paleontology, will be adding the donated fossils to the Oakland museum’s collection.

“Fossil like these are rare in the fossil record,” says Kollar, who has done research on invertebrate fossils and field work around the United States and other countries. “The addition of Cretaceous ticks in amber associated with feather dinosaurs adds an important group of specimens into the Invertebrate Paleontology collection at Carnegie Museum of Natural History.”

The fossils come from the Southeast Asian nation of Myanmar, where Spanish researchers from the Instituto Geologico y Minero de Espana in Madrid discovered ticks encased in Burmese amber from the middle Cretaceous Period—about 100 million years. Their discoveries included the new Dracula species, and one specimen is about eight times larger than its fellow ticks because it is so engorged with blood. The scientists also discovered specialized skin-beetle larvae attached to the legs of two Dracula ticks. Since these larvae feed on tough organic matter like skin, hair and feathers, the researchers suspect these ticks fed on feathered dinosaurs.

It is significant that these fossils were found in amber, which is fossilized tree resin that hardens over time into plastic. But extracting dinosaur DNA from amber only has happened in the movie “Jurassic Park.” Could the discovery of the ticks, and perhaps traces of dinosaur blood, lead us a step closer to a real-life version of the movie?

Scott Anderson—a co-author of the study, published in Nature Communications—donated the specimens to Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Anderson is a Pittsburgh-area geologist and amber collector.