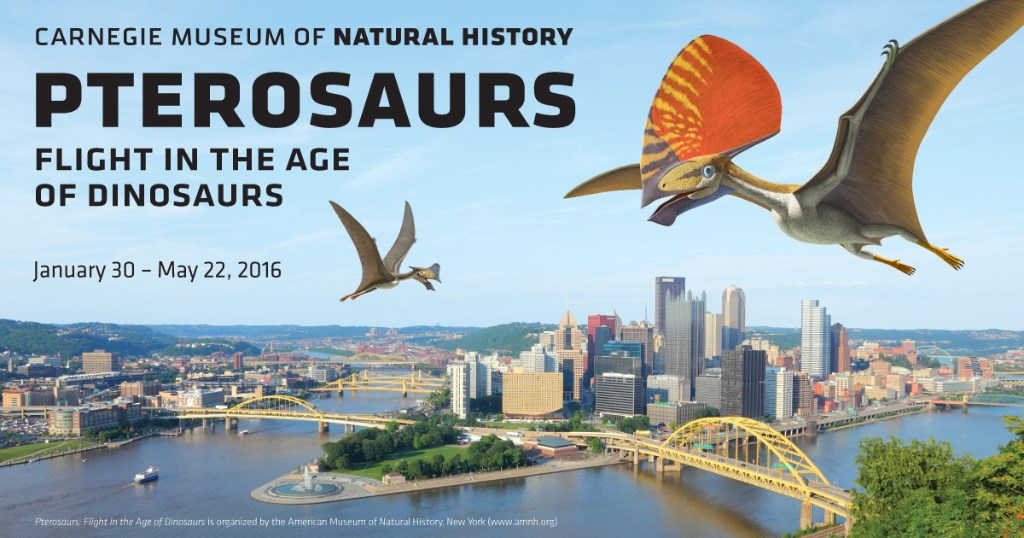

Carnegie Museum of Natural History will feature the largest pterosaur exhibition ever mounted in the United States running from January 30 to May 22, 2016. Pterosaurs, on loan from American Museum of Natural History in New York, highlights the latest research by Museum scientists and leading paleontologists around the world. It features rare pterosaur fossils and casts as well as life-size models, videos, and interactive exhibits that immerse visitors in the mechanics of pterosaur flight, including a motion sensor-based interactive that allows you to use your body to “pilot” two species of pterosaurs through virtual prehistoric landscapes.

“Most people find it very interesting to learn that Pterosaurs were not dinosaurs,” said Eric Dorfman, Director of the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. “They were close relatives of dinosaurs and the first back-boned animals to evolve powered flight.”

Interactive Exhibits

Several interactive exhibits help visitors see the world from a pterosaur’s-eye view. In Fly Like a Pterosaur, visitors can “pilot” two species of flying pterosaurs over prehistoric landscapes complete with forest, sea, and volcano in a whole-body interactive exhibit that uses motion-sensing technology. For a different perspective on flight, visitors can experiment with the principles of pterosaur aerodynamics in an interactive virtual wind tunnel that responds to the movements of their hands. Five iPad stations offer visitors the inside scoop on different pterosaur species—Pteranodon, Tupuxuara, Pterodaustro, Jeholopterus, and Dimorphodon —with animations of pterosaurs flying, walking, eating and displaying crests; multi-layered interactives that allow users to explore pterosaur fossils, behavior, and anatomy; and video clips featuring commentary from curators and other experts.

Unique Ability to Fly

Focusing on pterosaurs’ unique ability to fly, the exhibition also draws comparisons between pterosaurs and living winged vertebrates: birds and bats. Pterosaurs needed to generate lift just like birds and bats, but all three animal groups evolved the ability to fly independently, developing wings with distinct aerodynamic structures. The short film “Adapted for Flight” offers viewers a look at the basic principles of pterosaur flight and aerodynamics. A spectacular pterosaur fossil cast known as Dark Wing, on view for the first time outside of Germany, features preserved wing membranes and reveals long fibers that extended from the front to the back of this Ramphorhynchus pterosaur’s wings to form a series of stabilizing supports. These muscle fibers probably helped pterosaurs adjust the tension and shape of their wings.

Diversified Sizes and Head Crests

“Perhaps the most surprising discovery of this exhibit is the staggering variations we see among pterosaurs,” said Matthew Lamanna, Assistant Curator of Paleontology. “Not just variation in body shapes and in size, some ranged from the size of a bird to that of a plane, but also in the extravagant crests found on the heads of some of these creatures.”

When pterosaurs first appeared more than 220 million years ago, the earliest species were about the size of a modern seagull, but the group evolved into an array of species ranging from pint-size to truly gargantuan, including species that were the largest flying animals ever to have existed. Diversifying into more than 150 species of all shapes and sizes spreading across the planet over a period of 150 million years. Full-size models will be displayed including one of the largest and one of the smallest pterosaur species ever found: the colossalTropeognathus mesembrinus, with a wingspan of more than 25 feet, soaring overhead and the sparrow-sizeNemicolopterus crypticus, with a wingspan of 10 inches. Visitors can marvel at a full-size model of a 33-foot-wingspan Quetzalcoatlus northropi—the largest pterosaur species known to date—and the fossil remains of a giant pterosaur unearthed in Romania just two years ago, which point to a new species that was even stronger and heavier than Quetzalcoatlus.

Fossils

The exhibition features dozens of casts and replicas of fossils from the American Museum of Natural History collection and from museums around the world in addition to eight real fossil specimens, including a spectacular cast fossil that has never before been exhibited outside of Germany and the cast remains of an unknown species of giant pterosaur unearthed in Romania in 2012 by scientists working in association with the American Museum of Natural History.

Preservation

For paleontologists, pterosaurs present a special challenge: their thin and fragile bones preserve poorly, rendering pterosaur fossils even rarer than those of dinosaurs and other prehistoric animals. Several exhibits break down the fossilization process to show how the composition of pterosaur bones affects their potential for preservation. Visitors will also find out about conditions that produce particularly valuable fossils and view an exquisitely preserved three-dimensional fossil of Anhanguera santanae. The pterosaur, which died and fell into a lagoon in Brazil 110 million years ago, was buried by fine sediment and the mud formed a hard shell called a nodule around the remains, protecting and preserving the pterosaur for posterity.

Lifestyles: From Land to Air

Since pterosaur fossils are extremely scarce, and their closest living relatives—crocodiles and birds—are vastly different, even the most elementary questions of how these extinct animals flew, fed, mated, and raised their young are still mysteries. But recent discoveries have provided new clues to their behavior. Like other flying animals, pterosaurs spent part of their lives on the ground. Visitors will see a fossil track way from Utah that reveals pterosaurs walked on four limbs and may have congregated in flocks. A cast of the first known fossil pterosaur egg, found in China in 2004, shows that pterosaur young were likely primed for flight soon after hatching. What did pterosaurs eat? An interactive display shows their feeding habits varied widely, ranging from Pteranodon diving for fish, to Jeholopterus chasing insects through the air, to Pterodaustro straining food from water like a modern flamingo. A one-of-a-kind fossil treasure shows a Pteranodon’s last meal—the remains of a fish stuck in its mouth, preserved for 85 million years.

Pterosaurs likely lived in a range of habitats. But pterosaur fossils most easily preserved near water, so almost all species known today lived along a coast. The exhibition features a large diorama showing a re-creation of a dramatic Cretaceous seascape based entirely on fossil evidence and located at the present-day Araripe Basin in northeast Brazil. Two Thalassodromeus pterosaurs with impressive 14-foot wingspans swoop down to catch Rhacolepis fish in their toothless jaws, while a much larger Cladocyclus fish chases a school of Rhacolepis up to the surface. In the background, visitors will see an early crocodile and a spinosaurid dinosaur, which shared the habitat with pterosaurs.

Other fossils and casts offer additional clues about how pterosaurs lived and behaved. These include a fossil cast of Sordes pilosus, the first species to show that pterosaurs had a fuzzy coat and were probably warm-blooded, just like birds and bats, and even some dinosaurs. A gallery display illustrates the incredible variety of pterosaur crests—from the dagger-shaped blade that juts from the head of Pteranodon longiceps to Tupandactylus imperator’s giant, sail-like extension. Visitors can consider the many theories scientists have about how crests might have been used: for species recognition, sexual selection, heat regulation, steering through the air, or some combination of these functions.

Pterosaurs: Flight in the Age of Dinosaurs is organized by the American Museum of Natural History, New York (www.amnh.org). Locally, this exhibition is supported by Highmark Blue Cross Blue Shield, Dollar Bank, Pennsylvania Leadership Charter School, Baierl Subaru, Dunkin’ Donuts, and Bill Few Associates Wealth Management.