Philippine species Brachymeles burksi bears unique evolutionary lineage distinguishing it from other skinks

Discovery intensifies need for conservation

An international team of researchers announces the “resurrection” of the Philippine skink species Brachymeles burksi. The species, originally named in 1917 by Edward Harrison Taylor, was recategorized in 1956 as Brachymeles bonitae and has not been considered its own species since. In a paper published by the Philippine Journal of Systematic Biology, colleagues from Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Sam Noble Museum at the University of Oklahoma, University of Texas Rio Grande Valley, Philippine National Museum, and University of Kansas conclude that B. burksi represents a distinct evolutionary lineage making it a unique species.

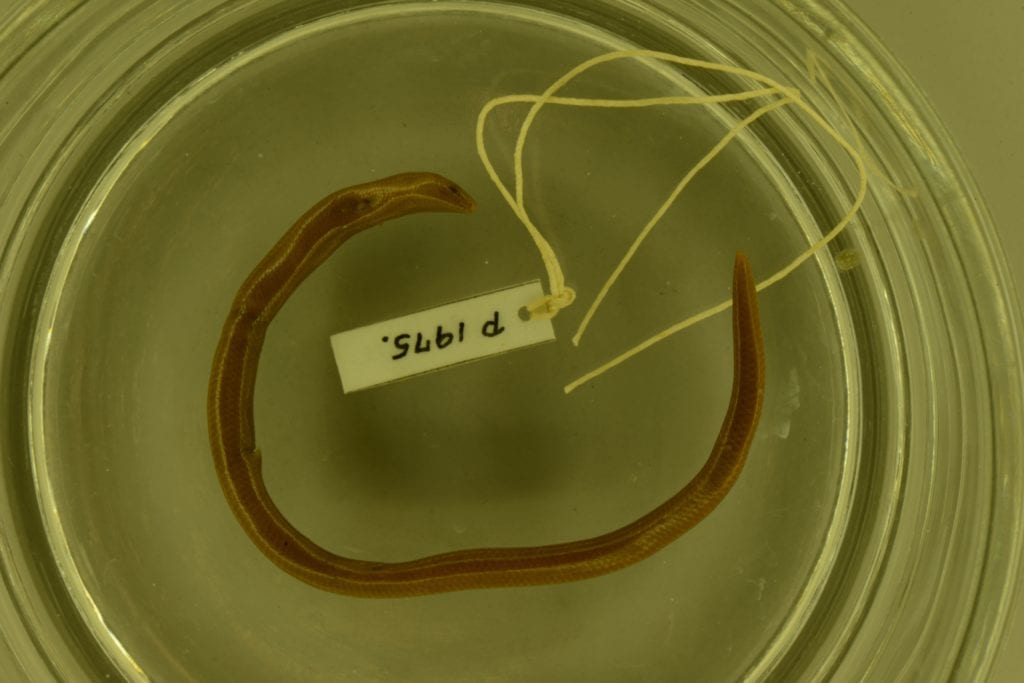

Skinks, among the most diverse groups of lizards, are generally recognized for their small legs and, in most cases, lack of a pronounced neck. The holotype, or single specimen upon which a new description and species name are based, of B. burksi is held in the herpetology collection at Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH).

“We are really lucky here at CMNH to have an incredible collection of 157 holotypes, many from the Philippines,” says Jennifer Sheridan, CMNH’s Curator of Amphibians and Reptiles. “My collaborators and I have worked on amphibians and reptiles of Southeast Asia for several decades, and I was excited to be invited to be part of this work. Southeast Asia has a high rate of new species description, which means that there are lots of species that haven’t yet been officially named and thus, whose conservation status cannot be assessed.”

The team confirmed that B. burksi is not only different from B. bonitae, but also confined to the islands of Marinduque and Mindoro, whereas B. bonitae is found on the much larger island of Luzon. “This means that B. burksi actually has quite a small geographic distribution,” Sheridan says, “which in turn means that populations on Marinduque and Mindoro are of even greater conservation concern than previously thought.”

Unlike B. bonitae, B. burksi has fewer presacral vertebrae, as well as fewer axilla–groin scale rows and paravertebral scale rows. Further, B. burksi represents a distinct evolutionary lineage from B. bonitae.

When scientists examine organisms, especially from groups that have variable morphologies, they sometimes reclassify species. Sheridan says, “Think of it as having two groups of individuals, A and B. Group A was described in 1839, and in 1917, scientists found group B and named it as a new species. Then in 1956 scientists said wait, group B individuals look the same as species A, so group B gets lumped with group A. Our recent work shows that actually, A and B are different, based on a combination of genetics, morphology, and geographic distribution.”

The Philippines, an archipelago of more than 7,100 islands, is recognized globally as a megadiverse nation and a biodiversity hotspot. Understanding of the diversity of Philippines amphibians and reptiles has increased significantly in the last decade thanks in part to closer analysis of poorly understood species complexes that are erroneously thought to be one species. This study, and others like it that identify and species-level diversity, will prove critical to developing effective conservation strategies for the Philippines.