by Anais Haftman

I am a fourth year biology student at Duquesne University who has had the pleasure to work in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles since 2021. Most of my time working in the section has been dedicated to cleaning the bones of specimens in the collection to ensure proper long-term preservation. With over 7,000 osteology (skeletal) specimens in the section, bone cleaning can be a tedious task. With the help of the museum’s Conservator Gretchen Anderson, and Collection Manager of Amphibians and Reptiles Stevie Kennedy-Gold, the long process of conserving and improving the quality of the osteologic specimens has been a breeze.

Why is a clean osteology collection important?

Conservation of specimens (wet and dry) in research collections is of the of the utmost importance because each specimen is a time and place record of species occurrence that can be re-examined as necessary. Some specimens are notable for having informed past research, and all specimens are held in public trust for their potential to inform current and future research. Because our specimens are routinely loaned out to researchers for use in studies, we work to ensure that their work is not diminished by ensuring the highest quality specimens possible. As the quality of a specimen decreases, the quality of information received from it also decreases.

What makes the osteology specimens unclean?

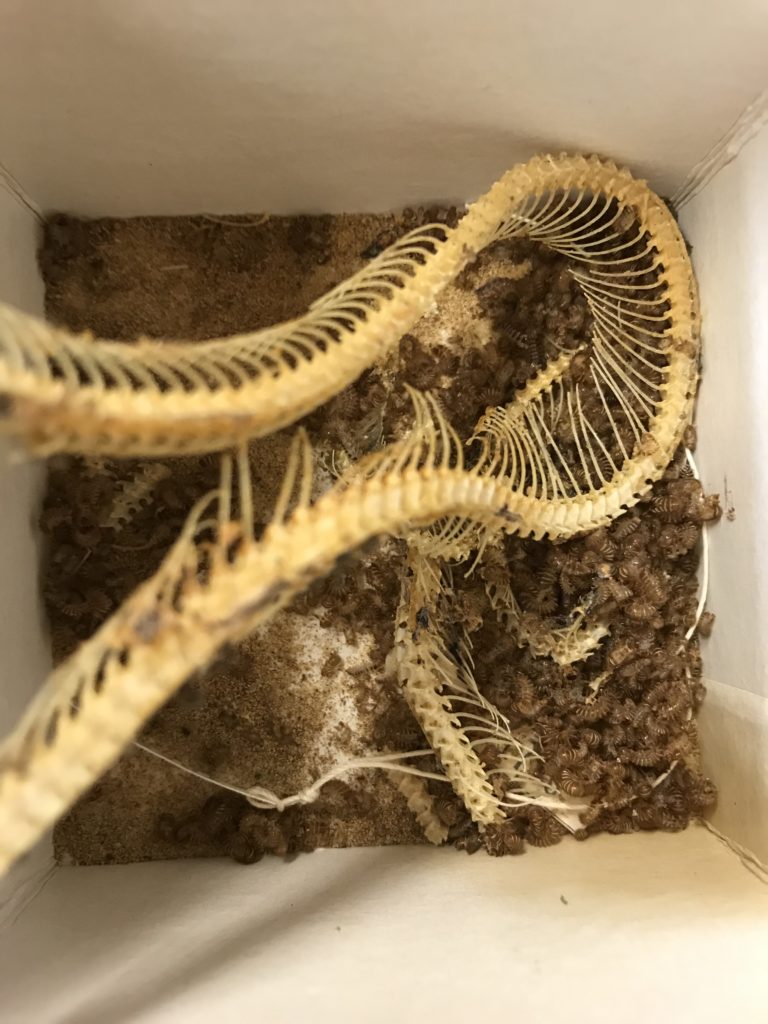

One of the most common culprits behind our need to clean bones are dermestid beetle larvae. But wait, why in the world would there be beetles in the bone boxes? Dermestid beetle larvae are commonly used to eat flesh and cartilage off specimens before they are added to the collection. During this process sometimes a larva or two wiggle themselves into small holes in the bones and are not seen when the bugs are cleaned off prior to storage. In these cases, we simply remove any long dead hitch-hiker larvae we find.

Sometimes natural oils and fats also remain on bones after the initial dermestid cleaning. In these cases, the cleaning process becomes more complicated. The most common circumstance that creates a need for cleaning, however, is the presence of inactive mold on specimens. Most of the time this issue can be easily solved by using a simple paint brush or Q-tip. But other times, particularly on large sturdy bones, I needed to put in a good amount of elbow grease!

How is the bone cleaning done?

Gretchen taught Stevie and I all we needed to know to properly clean bone specimens. The first step is always to visually inspect the specimen and record its condition. We make sure to write down its identifying collection number, what species it is, whether it’s a whole skeleton or only parts, if there were dermestid larvae still present on the specimen, and much more.

Once the data collection on the initial quality is complete, the cleaning can begin. We initially use a Nilfisk HEPA vacuum tube (a device we named R2-D2) to clean any inactive mold from the bones. Wearing protective masks, we manually loosen the mold and push it into the vacuum using paint brushes. Once the mold is removed, we are able to inspect the bones for presence of larvae or secreted oils. If there are larvae present, we carefully remove them with tweezers and put them in our “bug box.” If there are oils present, a Q-tip is used to clean it off. For smaller bones, such as individual vertebrae, a soak in 70% ethanol is often part of the cleaning process.

Depending on the quality and size of the osteological specimen, it can take anywhere from fifteen minutes to an hour to clean completely. Overall, much of the work to preserve osteologic specimens happens behind the scenes. This vital work is an example of the never-ending important tasks performed by both staff and volunteers that make the museum an important resource for scientific research.

Anais Haftman is a biology student at Duquesne University and works in the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles at the museum. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Digital Developments: Why Archiving and Herpetology Go Hand-in-Hand

Photos of Fluid-Preserved Specimens: A Different Kind of Portrait

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Haftman, AnaisPublication date: March 8, 2022