AMPHIBIANS & REPTILES (HERPETOLOGY) AT CARNEGIE MUSEUM OF NATURAL HISTORY

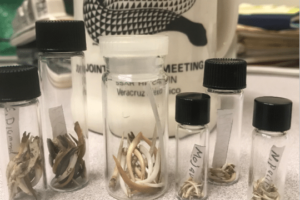

The Section of Herpetology maintains a collection of more than 230,000 specimens and ranks at about the ninth largest amphibian and reptile collection in the United States. Ninety-five percent of the specimens are fluid-preserved. Other specimens are preserved as skeletons, skins, mounts, or cleared and stained preparations.

The Section of Herpetology Collection Highlights

The Section of Herpetology includes the largest and most complete collection of Pennsylvania amphibians and reptiles in existence and significant collections from adjacent states, particularly Virginia, West Virginia, and Maryland. The section’s collection of North American freshwater turtles is among the largest in the world. The section maintains collections from over 160 countries. The largest and most significant holdings are from various regions:

| Africa 6,900 | Asia 11,900 | North America 190,000+ | Oceania 117 |

| Cameroon 1,466 | India 2,666 | United States 150,000+ | New Zealand 79 |

| South Africa 1,018 | Philippines 3,947 | Mexico 6,777 | |

| Angola 554 | Sri Lanka 940 | Bahamas 1,937 | South America 9,400 |

| Angola 554 | Costa Rica 1,859 | Bolivia 1,685 | |

| Namibia 540 | Europe 5,300 | Guatemala 1,705 | Paraguay 1,116 |

| Congo 392 | Spain 3,841 | Jamaica 1,424 | Brazil 1,066 |

| Zimbabwe 238 | Haiti 1,080 | Venezuela 989 | |

| Canada 907 | Colombia 909 | ||

| Belize 895 | Peru 886 | ||

| Anguilla 748 | Suriname 682 | ||

| Panama 815 | Argentina 826 | ||

| Honduras 548 | |||

| Cuba 495 |

Herpetology Collection Inquiries

Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Section of Amphibians and Reptiles collection can be found on VertNet, iDigBio, and GBIF.

For informal inquiries or if you wish to schedule a visit to the collection, please contact the collection manager by email.

Herpetology Collection Loans

The collections, tissues and archives of the Section of Amphibians and Reptilesare a research resource at the service of the research community. Preserved specimens and tissues can only be loaned to bona-fide academic and/or research institutions and should only be handled by trained individuals. The institution to which the loan is made is responsible for appropriately housing and caring for these materials during the loan period. Loans to individuals not affiliated with a research institution are not permitted.

Specimens requested by undergraduate or graduate students will be loaned to their advisor. For post-doctoral researchers or research associates, the loan must be co-signed by their advisor or a permanent faculty/staff member of the respective institution. In all cases the loan is considered the direct responsibility of the institution and its representative(s).

Type specimens and extinct specimens are not usually available for loan and sampling. However, authorization can be granted under special circumstances and at the discretion of the Head of Section.

1. REQUESTING A LOAN

Request of specimens for teaching purposes can only be accommodated if the requested taxa are available in the Section Teaching & Exchange collection.

Researchers wishing to request a loan should contact the Collection Manager (Mariana Marques) or the Curator (Jennifer Sheridan) directly. All requests must be presented in a signed document on institutional letterhead in PDF form.

- Complete mailing address, including detailed contact information such as email and phone number.

- List of specimens requested, including catalog number(s) and taxon/taxa name.

- Description of the project. This can be brief but must address why the specimen(s) is/are needed and which methods will be used.

- In case of the need of destructive sampling, all techniques and analysis should be noted. It should also be explained why non-destructive methods can’t be used.

- Signature of the applicant. If the request is made by a student or post-doc, the respective supervisor’s signature is required.

The request will be reviewed by the Curator and Collections Manager. The rarity of the species, its representation in CMNH collections, the loan history of the researcher, and the nature of the project (destructive vs. non-destructive) will be taken into account. Usually, no more than one-half of the total specimens’ holdings of a given taxa will be loaned in a single request. The remaining specimens of interest may be requested after return of the first loan.

Loan requests will be processed as promptly as possible and on a first-come, first-served basis. Loans within the US are normally addressed in one to two weeks. International loans will take longer due to required paperwork and customs clearance. Loans are generally granted for six months (1 year for tissue samples). Extensions must be requested in writing to the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles.

Limitations related to shipping, customs, CITES regulations, and national and international laws may interfere with the ability of the Section to approve international loan requests.

The borrowing institution is responsible for providing copies of all relevant permits for foreign loans, and their institutional CITES registration number, if applicable. If permits are not necessary, that should be stated in the original request.

IMPORTANT INFORMATION:To avoid potential losses during the shipping process, the CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles may defer loan requests between Thanksgiving and New Year. Please plan your request in advance and check with Section personnel on ability to ship loans during this time

2. TERMS FOR USE OF LOANED SPECIMENS

- The borrower must email the Collection Manager for the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles to acknowledge the safe receipt of the specimens as soon as they arrive. The borrower must check the number and condition of specimens, and note any damage or discrepancies on the appropriate copy of the loan invoice. One copy of the loan invoice, one copy of the specimen invoice and one copy of the loan agreement must be signed and returned to the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles electronically (PDF) or by post mail. The second copies of these documents are to be retained by the borrowing institution.

- No specimens may be exchanged, loaned, or re-gifted to a third party or cataloged into any collection without the express written permission of CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. Permission should be requested in writing to transport specimens from one institution to another in the case of a researcher’s relocation. The original loan must be closed, and a new loan process will then be then opened under the name and address of the new institution.

- Any labels associated with the specimens may not be removed or altered by the borrower without advance approval of the Section.

- No destructive sampling may be conducted without previous written permission from CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles.

- Specimens should be stored in an appropriate environment that follows the best standards for natural history collections preservation. All wet specimens must be stored in 70% non-denatured ethanol (or in the appropriate fluid as noted on the loan documents) and kept out of direct light. While examined, specimens should always be kept moist with 70% ethanol. Dry specimens are to be stored in a dry, humidity-controlled, pest-free environment.

- Specimens must be handled and examined with care to avoid damage. Do not force limbs, jaws, etc. into positions that tear muscles or break bones.

- The borrowing institution and person in charge should exercise the best standards in care and preservation of the material and assume responsibility for any loss or damage caused during the loan period. The CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles must be immediately notified in case of damage, loss, theft, or other change in condition of the specimen. In the case of any of the above situations, a condition report should must be written and sent to the Section.

- All taxonomic changes, including misidentifications and designation of types, must be reported to the CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. Researchers should notify the Section of any historical errors, questionable localities, dates, or any other problematic data found while examining loaned material.

- Any resulting publications should acknowledge CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. An electronic copy (PDF) of the publication must be emailed to the Section. For citation of specimens in a publication, please use the internationally recognized Institutional Collection Code and catalog number (CM XXXX).

- Specimens need to be returned to CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles following appropriate IATA dangerous goods packing and shipping regulations and shipped through an authorized carrier.

3. DESTRUCTIVE SAMPLING

- No destructive analyses, such as molecular or isotopic sampling, clearing and staining, dissection (including for sex determination), or making molds or casts of loaned material are allowed without previous approval from the CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles.

- Requests for destructive analysis, including complete suggested protocol, must be submitted with the initial loan request. Any changes to the destructive protocol that might occur during the loan period must be submitted to the Section.

- Removing tissue from specimens for genetic analysis is considered destructive sampling. A destructive sampling protocol must be included with the request. For DNA extraction from formalin-fixed specimens, the sampling and sequencing methods to be used, and a statement regarding the capacity of the borrowing institution to carry out such methods, should be included with the request.

- If the removal of specimen parts (e.g., tissues, stomach contents, reproductive organs) is approved by the Section, any resulting product (e.g., tissues, stomach contents, cleared and stained preparation, skeletal preparation, histological slide, etc.) must be returned with the specimens and labeled with the respective CM catalog number and date of the procedure.

- When dissections are authorized (e.g., sex determination, tissue sampling, stomach content removal) incisions must avoid cutting skeletal elements and viscera. Incisions should be kept as small as possible. For stomach contents, the studied contents should be removed and kept in a separate vial together with the specimen number. In the case of paired organs (e.g. testes, ovaries), only one may be removed.

- When an organ is sectioned, all microscopic slides produced must be labeled with the catalogue number and returned to the Section.

- Instructions for other types of sampling will be shared as appropriate.

4. RETURNING LOANS

Before or at the time of return, please send an email to the Collection Manager providing a possible date of shipment. Please send all tracking information associated with the package(s). For international shipments, return shipment notification must be made in advance to ensure that all legal and shipping documentation is filed in advance of shipment.

Please avoid returning specimens between Christmas and New Year. If the loan is due date is during this period, please contact the Collection Manager.

- Fluid specimens must be returned to CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles after the established loan period following appropriate IATA dangerous goods packing and shipping regulations and made through an authorized carrier. All international shipments should be returned by courier (FedEx, UPS, or DHL).

- Specimens should be wrapped in moist cheesecloth soaked in 70% ETOH. Excess alcohol should be removed and the soaked bundle should be placed in three layers of individually heat-sealed plastic bags. The second plastic bag should have an absorbent pad. The note below should be placed in the third and final plastic bag.

- Once the bundle is triple-bagged and heat sealed, place it into an appropriately sized box for shipping. There should be enough room in the box to liberally cushion the specimens with packing peanuts or air cushion packaging bags. Attach a tag with the following phrase: “Scientific Research Specimens. Not restricted. Special Provision A 180 applies.” on the exterior part of the box, in a way that it always remains visible. This applies for all domestic and international shipments.

- For domestic US shipments, attach the appropriate 49 CFR 173.4 regulation label (see below) for transportation of dangerous goods excepted quantities. This label should be placed on the side of each package to unambiguously indicate that the package conforms to regulation 49 CFR 173.4.

- Dry specimens should be returned in the same manner as they were sent by the Section. The packing will be dependent on the size, nature, and fragility of the specimen.

- The borrower is responsible for ensuring legal eligibility for returning specimens or tissues and providing copies of all relevant foreign import permits. Likewise, the borrower is responsible for providing copies of all relevant foreign export permits when specimens are returned. International loans should not be returned to CMNH without prior arrangement to ensure that all necessary permit paperwork accompanies the shipment. If permits are not necessary, that should be stated in writing at the time of the request.

- International importation of specimens of taxa regulated by the U.S. Fish and Wildlife Service (e.g., CITES, endangered species) will not be processed without proper U.S. import permits.

- All international shipments must be declared to the US Fish and Wildlife Services, and the loan should be accompanied by the US Fish and Wildlife form 3-177 provided by the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles for re-importation of specimens or tissues. The clearance of this re-importation processes takes a minimum of two (2) weeks, and borrowers should wait for the confirmation of the collection manager before shipping packages.

- International shipments should be accompanied by a letter, written on institutional letterhead, stating that the shipment is in accordance with all relevant international and national regulations for the transportation of scientific specimens, as well as an invoice with a detailed list of the material being transported. Please place the correct HS-Code (9705.00 -Collections of zoological / botanical / mineralogical archaeological / paleontological interest)) in your invoice and institutional letter, and the number of the airway bill.

- Physical copies of all documentation must be placed both inside the package and attached to the outside of the shipping box to facilitate inspection upon re-importation. An electronic copy must also be sent to the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles.

- Specimens should be shipped to:

Mariana P. Marques

Carnegie Museum of Natural History

Section of Amphibians and Reptiles

4400 Forbes Avenue

Pittsburgh, PA 15213, USA

5. REQUEST AND USE OF PHOTOGRAPHS, FIELD NOTES, AND CORRESPONDENCE

- Researchers wishing to borrow photographs, field notes, and correspondence from the CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles, should contact the Collection Manager (Mariana Marques) or the Curator (Jennifer Sheridan) directly.

- Researchers should briefly describe the project sufficiently to address why the photograph or archival material is needed.

- Photographs of specimens, field notebook pages, correspondence, and other archival materials may not be reproduced, distributed, publicly displayed, or otherwise used, in whole or in part, without written permission from the CMNH Section of Amphibians and Reptiles. No materials should be used for commercial purposes without prior consent of the Section and CMNH board of trustees.

- When permission is given, these digital images may be used, downloaded, reproduced, used in a publication, publicly displayed, distributed, or reprinted by persons affiliated with academic and/or non-profit organizations for scientific and scholarly purposes only. An acknowledgement of the permission to use these images/files must be noted. The photographed specimen or archival material must be correctly identified with its respective catalog number.

- Use of photographs or other archival materials on personal or academic web sites must be authorized by the Section. Images must be credited to “Carnegie Museum of Natural History, Section of Amphibians and Reptiles”.

Herpetology Blogs

From Collections User To Collections Manager

Introducing Mariana Marques, the New Collection Manager for the Section of Amphibians and Reptiles by Mariana Marques I’m not sure when I …

Getting Started: a high school intern’s experience in the herp section

by Jaylynn Smith Curator note: We currently have an intern from a local high school working with us for ten weeks. The …

An Illuminating Tale of Tracking Turtles

by Amanda K. Martin *All research was conducted under approved permits from by IACUC, ODNR, and Metroparks. Do not try this at …

Introducing Matt Brandley, the Herpetology Collection’s New Science Communicator and Research Associate

Every herpetologist has an origin story – a time in their life when they realize that they want to spend their time …

Nerding Out Over Masting, or Why Unusual Plant Reproduction Excites Animal Ecologists

As for many people, every pandemic month that passes marks another month since I’ve been able to travel. I realized recently that …

A Head Above the Rest: Unearthing the Story of Our Leatherback Sea Turtle

When you think of BIG sea creatures, you probably imagine great white sharks, huge blue whales, or ginormous cephalopods like the giant …

Digital Developments: Why Archiving and Herpetology Go Hand-in-Hand

Careers in librarianship are often depicted as quiet, solitary positions that allow ample time for reading on the job. Images associated with …

Do Snakes Believe in the Tooth Fairy?

When a child loses a baby tooth, the Tooth Fairy will sneakily appear a short time later to snatch that tooth up …

Overwintering for Amphibians and Reptiles

by Amanda Martin With Autumn upon us, temperatures are dropping, and it is getting colder out. Especially in the northern regions, amphibians …

Section of Herpetology Collection Featured in Museum Displays

There are three cases of reptiles and amphibians featured on the Daniel G. & Carole L. Kamin T. Rex Overlook on the second floor of the museum. There are a few amphibians and reptiles scattered in the dioramas in the halls of African and North American Wildlife and Botany Hall. Discovery Basecamp, in the rear of the building, has a cast of an enormous leatherback turtle suspended from the ceiling as well as some miscellaneous specimens on exhibit.

History of the Section of Herpetology

D.A. Atkinson

D. A. Atkinson began as an undergraduate student while attending Western University of Pennsylvania, later renamed the University of Pittsburgh. Atkinson was an overall naturalist, which was common at the time, and added specimens to many of the collections at the museum. He spent one full summer in 1899 surveying Allegheny County, providing the baseline data for studies that would follow later. After further schooling, Atkinson obtained a medical degree but continued to be connected with the museum. He was an integral partner in a number of field trips to several counties in Pennsylvania and one grand collection trip through Oklahoma and Texas, which provided a number of specimens that were mounted for exhibit. Atkinson accompanied former Carnegie Museum of Natural History Botany Curator Otto Emory Jennings on a trip to Isle of Pines in 1910. Atkinson served Amphibians and Reptiles as a field collector from 1900 to 1902, a volunteer custodian from 1907 to 1914, and an honorary curator from 1923 to 1938. He was instrumental in laying the foundation of the collection, collecting well more than 4,000 specimens.

Lawrence Griffith

Lawrence Griffith, PhD, custodian and honorary curator to the Section of Herpetology was a professor of biology at the University of Pittsburgh and a snake specialist. He began cataloguing some of the early specimens obtained from Herbert Huntington Smith and John D. Haseman, both of whom had made interesting acquisitions in South America. Griffith had done previous fieldwork in the Philippines, but his field trips while in Pittsburgh were to California, Arizona, New Mexico, and New Jersey, where he collected more than 800 specimens. His tenure here was from 1915 to 1920, and he functioned more as an honorary curator, though his title was custodian. He published a number of important papers during his stay and built much of the South American collection.

Graham Netting

M. Graham Netting’s association with Carnegie Museum of Natural History started when he was an 18-year-old student at the University of Pittsburgh, working initially in the Section of Birds for the sum of 35 cents an hour. He began to also work in the Section of Herpetology in 1924 and became the first full-time staff member in the section in 1926 upon graduation. In 1928, Netting left to pursue a doctorate at the University of Michigan. The stock market crash interrupted his pursuit of his doctorate, and he came back to his beloved museum.

Netting was the consummate curator and “museologist” before the term had been invented. Netting began building and organizing a strong collection from the bits and pieces contributed prior to his employment and using the aforementioned associates. Netting initially went on field trips to various parts of Pennsylvania and to California in 1925. By 1927, he had visited Guadeloupe, Barbados, and Trinidad. He returned to South America in 1929, visiting Trinidad and Venezuela, continuing into 1930 spending five months in the field. After this trip, his attention was drawn to the Appalachian region of eastern North America, primarily concentrating on salamanders, but still collecting all groups from North Carolina, West Virginia, Pennsylvania, and states in between. Additionally, Netting travelled to Panama in 1934. He facilitated relationships with quite a number of herpetologists and either persuaded them to donate their collections here, provide funds to help with field work, or purchase their specimens. Important collections were obtained from Roger Conant and others from eastern Pennsylvania, Paul and David Swanson from northwestern Pennsylvania, and others such as John Dolan, Coleman Goin, Carl Gans, James A. Fowler, Neil Richmond, Leonard Llewellyn, and N. Bayard Green, who provided specimens from wide-ranging regions of the United States. There was also growth in the early years from outside the United States with collections from Africa by Albert Irwin Good (ca. 1,500 specimens) and Rudyerd Boulton (1,000 specimens), South America by Jose Steinbach (1,200 specimens), and the Philippines with an important collection from Edward H. Taylor (more than 2,000 specimens).

By 1949, the Section of Herpetology collection had grown to almost 58,000 specimens and was one of the top collections in the country. Netting kept meticulous records and was aware early in his career of the importance of locality information and geography. Netting also taught geography, zoology, and herpetology from 1944 to 1963 at the University of Pittsburgh and was secretary of the American Society of Ichthyologists and Herpetologists from 1931 to 1947 and later as president from 1948 to 1950.

Netting was a curator from 1931 to 1954. From 1949 to 1953, he also served as assistant director. In 1954, Graham became director of Carnegie Natural History Museum and served until 1975 when he retired to a house near Powdermill Nature Reserve, the museum’s environmental research station that he helped create in the mid-1950s. He helped found many of the environmental organizations in Pennsylvania, including the Western Pennsylvania Conservancy and the concept of the Pennsylvania Department of Environmental Protection.

Because of the increased importance of the Section of Herpetology collection, along with the administrative duties in which Netting became involved, a second employee in the section was hired.

Grace Orton

Grace Orton worked at Carnegie Museum of Natural History from 1945 to 1950 after obtaining her degree from the University of Florida, concentrating her study on early development in frogs. She built a substantial collection of comparative stages for many amphibian species with more than 400 developmental series.

Neil D. Richmond

Neil D. Richmond was hired to replace Orton in 1951. He had a long association with Carnegie Museum of Natural History, initially through Netting when he was doing fieldwork in West Virginia. Richmond had surveyed much of West Virginia when he was employed at Marshall College from 1938 to 1939, and Netting had spent much time in that state doing field work. Richmond also had spent a fair amount of time in Pennsylvania doing field work in the state mammal survey from 1948 to 1949. While serving as curator until 1972, he conducted fieldwork in Virginia, West Virginia, and Pennsylvania, and he conducted four expeditions to the Bahamas, ultimately depositing close to 5,000 specimens in the collection.

CJ “Jack” McCoy

CJ “Jack” McCoy was hired as an assistant curator in 1964 and immediately began to have a major impact. Like Netting, McCoy had been trained in collection management and began a rigorous program to curate and update the collection and then to build the collection through exchange and friendships with colleagues.

Unlike most of the predecessors in the section, McCoy was more interested in reptiles, doing most of his previous research on lizards but with occasional papers on snakes. Beginning in the mid-1970s he added turtles into the mix and over the next two decades built one of the largest turtle collections in North America.

McCoy befriended a large group of field researchers over his span as curator from 1964 until he passed away in 1993. Many of them considered him their mentor, and he instilled in them a great desire to understand the environment through amphibians and reptiles. The section had unprecedented growth over those 30 years, adding at least 100,000 specimens. The collections came here by purchase, targeted fieldwork, orphaned collections, or surveys conducted either through McCoy or from friends who sent the collections here for safekeeping. The collaborators are almost too many to name, but a few of the most important contributors include Richard C. Vogt, Michael A. Ewert, Stephen D. Busack, Paul S. Freed, Edwardo C. Welling, Donald E. Hahn, Arthur C. Hulse, Anthony C. Krzysik, Stephen R. Williams, Edward O. Moll, Barry Valentine, Andrew H. Price, David J Morafka, James J. Bull, Russell J. Hall, Robert G. Jaeger, and Joseph C. Mitchell, who brought much of his collection here along with those made in Virginia by Chrispher Pague, Kurt Buhlman, and David A. Young.

McCoy also helped establish scientists early in their careers by co-authoring papers with them. The list is long, but most notable pupils were Oscar Flores Villela, Gustavo Casas, Lucy Aquino, Frederico Achaval, Daniel Garcia Sanchez, and Alfredo Salvador.

Ellen J. Censky

During the search for a successor to McCoy, two curators were hired. In 1994 Ellen J. Censky became assistant curator after assuming head of section in 1993. She had worked in the collection since 1979 and been trained in all manner of collection maintenance as well as doing research via McCoy. She had previously done field work in many of the United States as well as in Belize, Paraguay, Costa Rica, and the Caribbean, where she conducted research toward her PhD in Anguilla.

John J. Wiens

John J. Wiens joined Censky as a curator after completing his dissertation at Kansas in 1995.

Having two curators had occurred many times in the past, with McCoy’s overlap with Richmond for eight years and Netting’s overlap with Orton and Richmond for many years. Duties were split between two curators—Censky primarily handled collection duties, and Wiens being able to concentrate on research. Censky left in late 1998 to take a job as a director of a small museum.

Wiens was a prodigious researcher and cranked out over six major publications a year through his tenure here. He was credited with establishing a the molecular phylogenetics laboratory at Carnegie Museum of Natural History and brought in Christopher L. Parkinson to set up the lab. During this same period, the section had Robert E. Espinoza as a Rea Postdoctoral Fellow, making the section very prominent in the museum

Wiens left to become a professor at Stony Brook University in New York at the end of 2002, leaving the section with only a collection manager until November of 2012 when José Padial became assistant curator in the section.

José Padial

Padial worked at Carnegie Museum of Natural History for just over four years. He took four very successful field trips in 2013, 2014, 2015, and 2016 to Amazonian Peru, exploring in each successive trip new areas of the jungle and documenting the fauna of the area. His final trip to Amazonian Peru in association with Carnegie Museum of Natural History was funded by the Carnegie Discoverers. There is a great probability that at least a dozen new species were discovered on that expedition. Padial moved to New York in December 2016 and remained on at Carnegie Museum of Natural History as a research associate to study the specimens from his final trip and continue his work on a publication of the results.