by Sabrina S. Robinson and Timothy A. Pearce

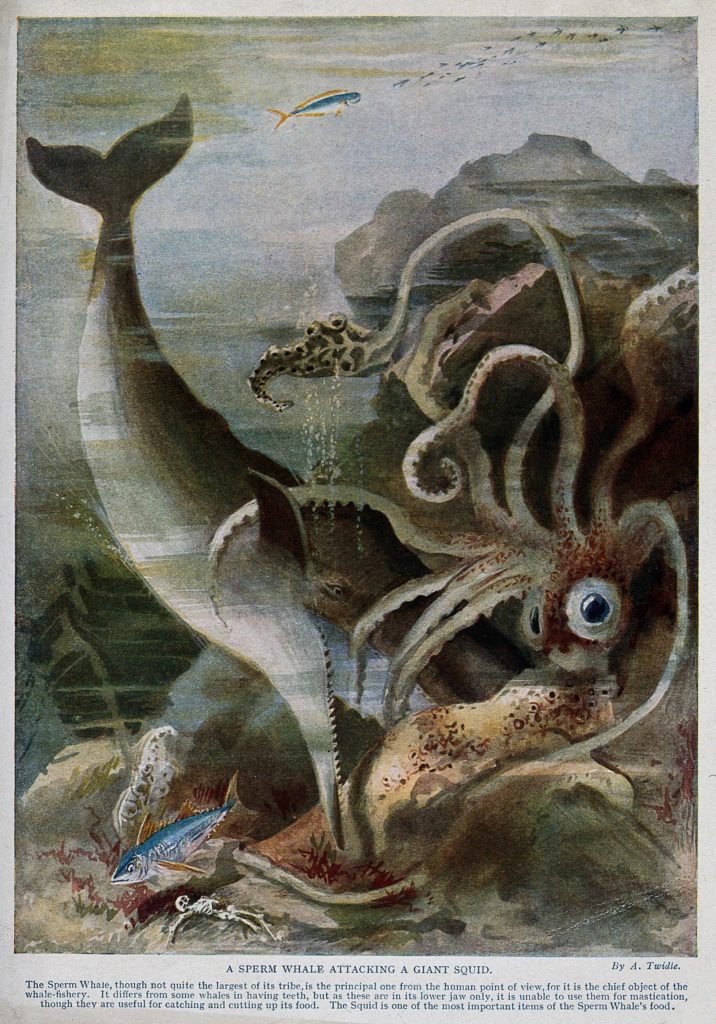

We’ve all heard the legend of the sperm whale and the giant squid, locked in epic battles in the waters of the deep, like that imagined in Jules Verne’s 20,000 Leagues Under the Sea (and yes, sperm whales do love to eat giant squids). If one substituted a shark for the whale, most of us would think the squid — or its relation, the octopus — wouldn’t have much chance. But that assumption might be wrong…and in fact, evidence from nearly one hundred million years ago hints at surprising mortal interactions between shark-like vertebrates and cephalopods.

Octopuses vs. Sharks

In 2000, with some trepidation, a Giant Pacific Octopus was placed in a large tank with sharks at the Seattle Aquarium. At the time, some aquarium staff wondered whether the octopus would be attacked by the sharks. It turned out that the trepidation was justified, but for precisely opposite reasons: sharks started disappearing (and perhaps the octopus began to look too self-satisfied). Several years later a video, which subsequently went viral, was filmed at the aquarium showing an octopus attacking and eating a dogfish shark. As in many videos produced for nature documentaries, the creatures were subject to human interference (not to ruin nature documentaries for you); divers directed dogfish toward the octopus. Despite this meddling, the fact remains: sharks, beware.

Ammonites vs. Mosasaurs

Ammonites and ammonoids were ancient cephalopods that became extinct at the end of the Cretaceous. Fossilized ammonite shells have been found with indentations that some paleontologists interpret as bite marks from mosasaurs. (An alternate explanation is that the mosasaur bites were holes made by limpets, marine gastropods, some species of which scrape holes into calcium carbonate surfaces, such as other shells [Seilacher 1998], although some paleontologists continue to defend the mosasaur bite hypothesis [Tsujita & Westermann 2001]. Mosasaurs were part of a group of extinct ocean-going reptiles, having the body form and presumably the behaviors of sharks. In other words, this mollusk vs. shark(ish) conflict might be a blood feud going back 90 million years or more.

So, let’s say that it was mosasaurs (and not nibbling limpets) snacking on the ammonites, and that all of this adds up to a pattern, leaving the question: do the mollusks or the sharks and shark-like reptiles have the intellectual advantage in the fight? Modern squids and octopuses, collectively classified as coleoids, are famous for their intelligence and quick wit. It’s difficult to know whether ammonites shared this cleverness — coleoids and ammonites descend from a common ancestor known as a bactritid, and we don’t know how intelligent this ancestral creature was. The modern chambered nautilus, resembling ammonites though not closely related to them, does not seem to be very smart (but it does have a remarkable memory).

Squids vs. Ichthyosaurs

Here is additional possible evidence of ancient intelligence shaping the feud between mollusks and shark-like reptiles. Fossils of shell-less cephalopods are rare, but the creatures’ presence in the fossil record is sometimes detectable through their preserved bird-like beaks and gladii (singular is gladius), a hard pen-shaped internal structure of squid. The beak remains of a large fossil squid with a body length estimated to be at least 10 meters were found in Nevada near multiple ichthyosaur vertebrae arranged in an unusual pattern. This peculiar circumstance, which had been seen elsewhere in the fossil record, led at least one paleontologist to speculate that the bones had been deliberately arranged by a large squid (who presumably killed the vertebrate), perhaps as a self-portrait! Ichthyosaurs, like mosasaurs, are shark-like in body plan and (presumably) behavior.

Of course, this is a highly controversial idea — but creatures making art on the seabed has at least some precedent. In 2011, Matsura Keiichi solved a mystery in the sands of the sea floor around the Ryukyu Islands, a chain of Japanese islands on the boundary between the East China Sea and the Philippine Sea. Complex and beautiful circular patterns had been found by divers in these underwater sands for years. It was finally discovered that the white spotted pufferfish (Torquigener albomaculosus), was making these works of art as a courtship display, carefully constructing and maintaining them, until a female, enticed by their sculpture, spawned in the center of the circle, leaving the artistic male to care for the eggs. (See a video of one adorable little guy making his art on PBS.) So underwater art is a known explanation for strange seabed arrangements.

We’re reminded of the Arnold Schwarzenegger movie Predator, in which the Predator’s trophies from its kills were spinal columns. Could this ancient kraken have been the original Predator, collecting its victims’ spinal columns? Constructing displays with them to attract mates??

Which reminds us of a joke. Tim’s friend called him on the phone to say he was changing his name to Spinal Column. Tim asked, “Umm, can I call you Back?”

Sabrina Robinson is a volunteer in the Section of Mollusks. Tim Pearce is Curator of Collection in the Section of Mollusks.

Related Content

How to Talk with an Extra-Terrestrial Alien? Practice with an Octopus

Prozac and Caffeine in Our Wastewater: Effect on Freshwater Mollusks

Oysters Swim Towards a Siren Soundscape

Carnegie Museum of Natural History Blog Citation Information

Blog author: Pearce, Timothy A.; Robinson, Sabrina S.Publication date: November 17, 2022