Land snails are leaky bags of water that survive on dry land. Snails lose water through evaporation, and because mucus is more than 90% water, they must expend water just to move, gliding on their silvery slime trails. Most land snails occur in moist environments where they can readily replenish lost water. But some snails live in the desert or other arid areas! How is that even possible?

Several strategies help snails survive in arid situations. For example, some close their aperture with a door or with a mucus sheet, some have small apertures or modify their growth direction to make better seals, some have mucus that inhibits evaporation, and some manage moisture loss by choice of microhabitats.

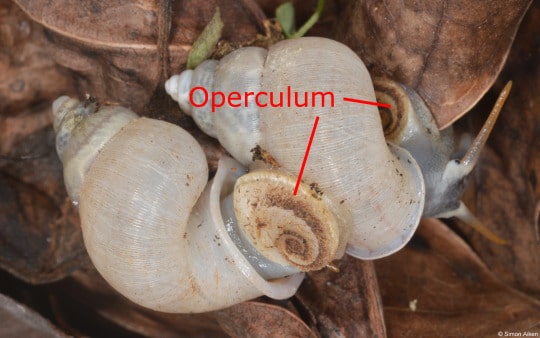

An operculum, or door, closes the shell in some land snails (Fig. 1), although most land snails lack one. The operculum is attached to the rear of the snail’s tail; when the snail pulls into its shell, the tail withdraws last and positions the operculum to make a tight seal. In addition to protecting the snail from water loss, it also protects from predators.

Snails that don’t have an operculum can cover the aperture with a mucus sheet called an epiphragm. In most snails, the epiphragm is thin and clear, but in some species, the epiphragm can be thick and opaque (Fig. 2). During dry periods, snails can form an epiphragm over the aperture or they can make a tight mucus seal between the aperture edges and substrates such as a rock or plant. The seal helps to retard evaporative water loss. Some snails in the desert remain sealed under a rock for years before a rainstorm wakes them.

Snails of arid areas usually have a relatively small aperture (Fig. 3). The smaller surface-area-to-volume ratio reduces moisture loss through evaporation. Just like you would lose less heat (on a cold day) with your parka zipped up and your hood cinched around your face, the snail loses less water with less of its skin exposed, as in the case of a smaller aperture.

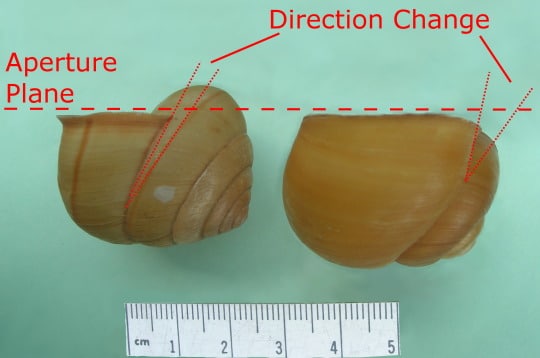

As growing snails approach their final size, many dip the direction of shell growth toward the shell base (Fig. 4). This results in the plane of the aperture making a tighter seal on a flat surface. Snails of arid areas tend to have shells that make tighter seals on flat surfaces than snails of moister areas.

The mucus of some species retards evaporation. Snails produce different kinds of mucus, for example, the mucus they glide upon to move, sticky or distasteful mucus when irritated, and mucus on their skin that can retard evaporation. One day when I was traveling in northern Kenya during the dry season after at least 6 months without rain, I was surprised to find a semi-slug (a gastropod whose shell is too small to fit the entire body) resting among some dry leaves and soil (Fig 5). It must have had special mucus covering the body that retarded water loss, allowing this species to survive many months of aridity.

Finally, snails influence their moisture loss by choosing their microhabitats. Some snails burrow underground during hot, dry weather to escape the heat. Other snails crawl under moist logs or descend deep into rock piles to avoid the harshest weather.

Why would snails even choose to live in the desert? I’m not sure anyone knows the answer for sure. My guess is that snails might live in a desert because it allows them to escape predators or competitors who can’t or don’t want to live there.

How do they do it? Snails survive in the desert by leaking water a bit more slowly than snails in moist areas.

Timothy A. Pearce, PhD, is the head of the mollusks section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.