by Marc L. Yergin and Timothy A. Pearce

Yes, some sponges live in freshwater. Before our recent finds, only one species of sponge had been reported from western Pennsylvania.

As you walk along a western Pennsylvania stream, you may notice a tan or brown encrustation on rocks or sticks in the water. The encrustation might superficially look like algae, but if you notice regular holes, you might have found a sponge. Scientists first categorized sponges as plants until it was noticed the organisms were pumping water in and out, which plants don’t do.

Sponges (phylum Porifera) are the simplest multi-cellular animals. They are considered the sister group to all other multi-cellular animals. They don’t have organs or tissues like we do. Nevertheless, we share 70% of our DNA with sponges.

Freshwater sponges account for less than 3 percent of the total 10,000 species of modern sponges on earth, most of which are marine. Only 31 species of freshwater sponges are found in North America.

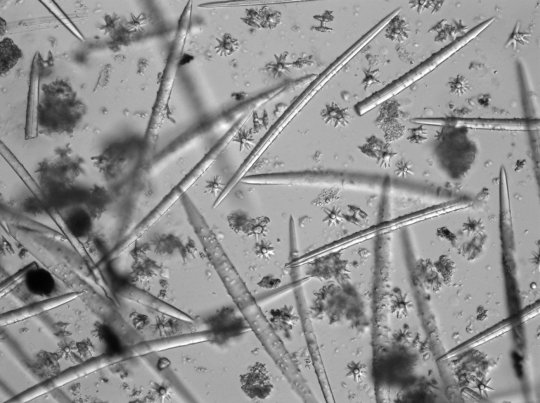

Our study, so far, found two additional species of freshwater sponges in western Pennsylvania, Ephydatia muelleri (Fig. 1) and Ephydatia fluviatilis. Because our species look alike, we tell them apart by examining their microscopic skeletal elements, called spicules. Spicules are made of silica, the same material found in sand and glass. The shape and form of the spicules are used to identify these sponges.

Spicules come in many different sizes and shapes. The larger spicules for the two species we found are called megascleres and look like double-pointed needles. The smaller spicules, called gemmuloscleres, look like dumbbells and provide protection in sponge reproductive structures (Fig. 2).

Sponges eat microorganisms by capturing and ingesting them from the water. Water is circulated through canals lined by cells with flagella (hair-like projections) that trap food particles. The water flows by every cell so oxygen can enter and carbon dioxide can be expelled.

The presence of sponges indicates good water quality with little or no contamination from acid mine drainage or sediment from agricultural field runoff.

Timothy A. Pearce, PhD, is the head of the mollusks section at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.