Spring is here, and the flowers are blooming! Not all flowers bloom at the same time, but with these instructions and a few supplies, you can make your own beautiful paper bouquet of spring flowers that will last all year. Plus, learn a few facts about their living counterparts and why plants are more interesting than you might think with Mason Heberling, assistant curator and Sarah Williams, curatorial assistant in the Section of Botany at the museum! *This activity requires a grown-up!

Before we start, let’s talk about spring flowers!

Many plants that go dormant in the winter, or stop growth, like hibernation for plants respond to certain cues so that they emerge and bloom at the “right” time. These cues include spring temperatures, length of daylight, known as photoperiod, and a set length of cold period (known as vernalization or “winter chilling”). It’s complicated and we are still learning how different species respond differently to each of these cues.

Like many spring flowers, both in your gardens and in the woods, the plants we are making today have big belowground structures called bulbs. Perennial plants with bulbs are known as geophytes (“geo” meaning earth and “phyte” meaning plant), these belowground bulbs come in many forms but serve as storage for energy (sugars) and water. Many geophytes can live many years and because their bulbs are protected belowground, have evolved to withstand many stresses, including fire, extreme temperatures, lack of water, and more. When the soil warms, sometimes even the slightest amount, in the spring, these belowground bulbs fill with water, cells expand, and out of the ground comes the beautiful flower! These flowers are not only beautiful to us—they signal to attract insects and wake up the web of life in our region.

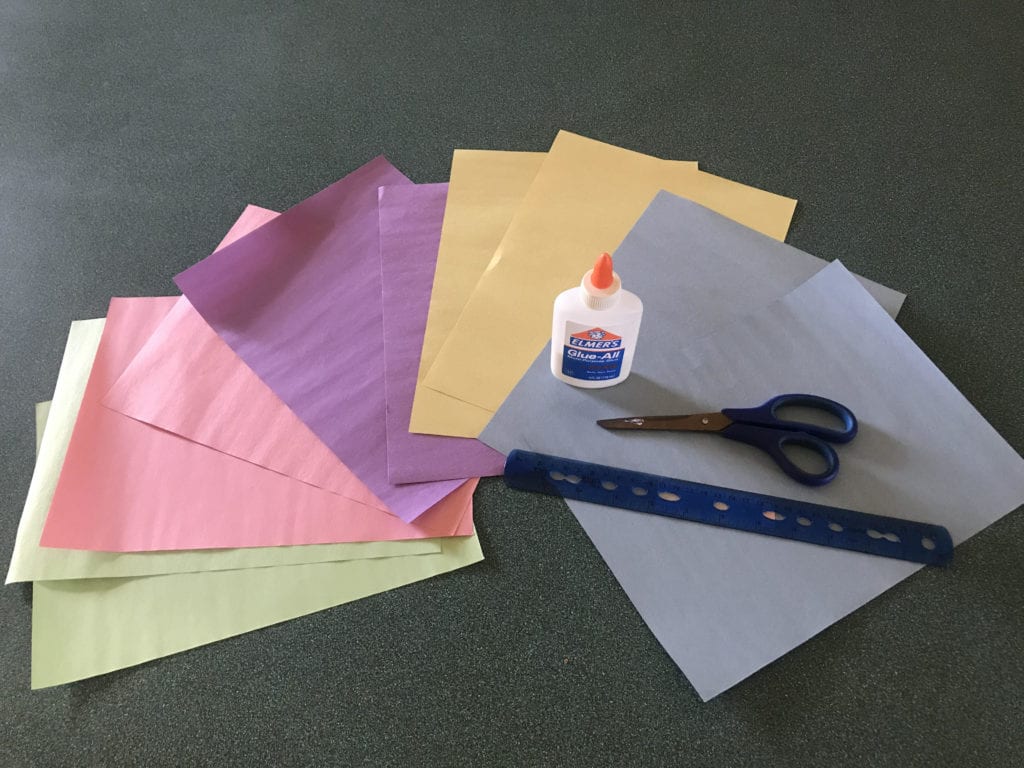

What You’ll Need

- Colored construction paper or card stock (make sure to have green paper for the stems!)

- Scissors

- Pencil

- A small surface to roll paper (this project used the end of a paintbrush)

- A ruler

- Glue

- *OPTIONAL* Green Pipe Cleaners for stems instead of green paper

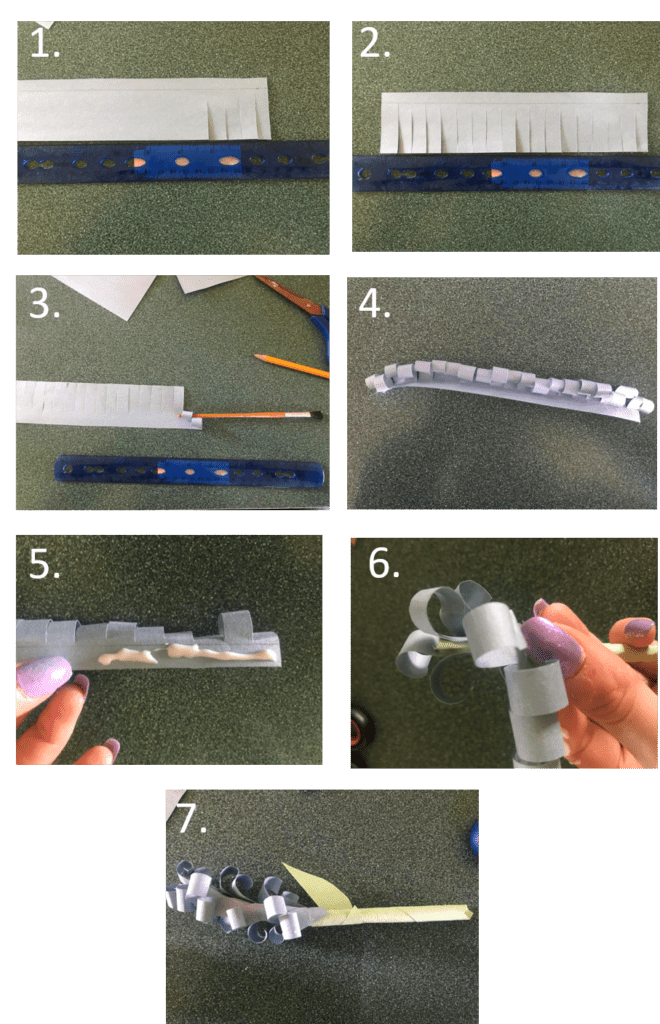

How to Make a Paper Hyacinth

- Measure and cut a 9×2 (or, if you are using cardstock, 8/8.5×2) rectangle from your colored paper (this is for the flower portion, please see the directions below on how to make stems and leaves. Measure out 3/8’’ from the bottom of your 9×2 rectangle and draw a line across the entire length of one side. Cut out small rectangles roughly 1/4’’ in size (these don’t need to be accurately measured and look more natural when a little different in sizes!), stopping before the pencil line at the top of the rectangle.

- Repeat your cuts across the length of the entire rectangle. Flip your rectangle over to hide the pencil marks.

- Using a small surface to roll your paper (like a pencil), roll each strip tightly (it’s ok if they loosen at any point during construction, just make sure they’re still rolled a little).

- Flip your rolled-up strips so that your pencil marks from earlier are facing up

- Glue along the bottom of the rectangle

- Make a paper stem and some leaves, or use green pipe cleaners. Holding your stem and your rolled-up strips, begin by placing the end of the roll to the top of the stem and slowly work your way down by spinning the stem (this may take several minutes—just go slowly and hold your roll to the stem for a few seconds until it has a chance to stick!). Continue down until the end of the roll

- Wait for the glue to fully dry before adding leaves

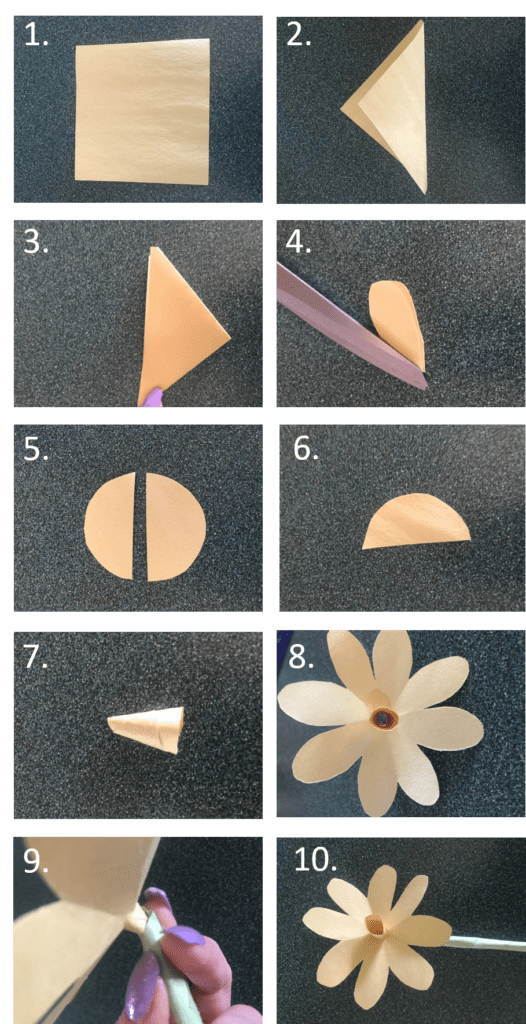

How to Make a Paper Daffodil

- Cut out a 4×4 square from your paper

- Fold your paper diagonally to make a triangle.

- Fold your paper in half two more times to make a smaller triangle.

- Cut a petal shape from the end of the outer corner of you triangle to the inner corner where all of the folds meet. Cut off the tip of the inner corner of your triangle.

- Cut a circle out of your paper (size doesn’t matter, but don’t make it too small!).

- Cut your circle in half.

- Using one half of your circle, fold it into a cone.

- Unfold your petal shape from step 4—it should look like a flower with a hold in the center (if it doesn’t, repeat the first steps and cut the petal shape from the opposite direction). Glue your cone from step 7 into the middle of the flower and hold it in place until the glue dries.

- Gently push your cone through the center of the daffodil and glue where the sides of the cone meet the petals.

- Create a stem (or use pipe cleaners), and glue the end of the stem to your daffodil.

- Hold the daffodil in place for a few moments while the glue dries.

- Create a leaf or two and glue to your stem.

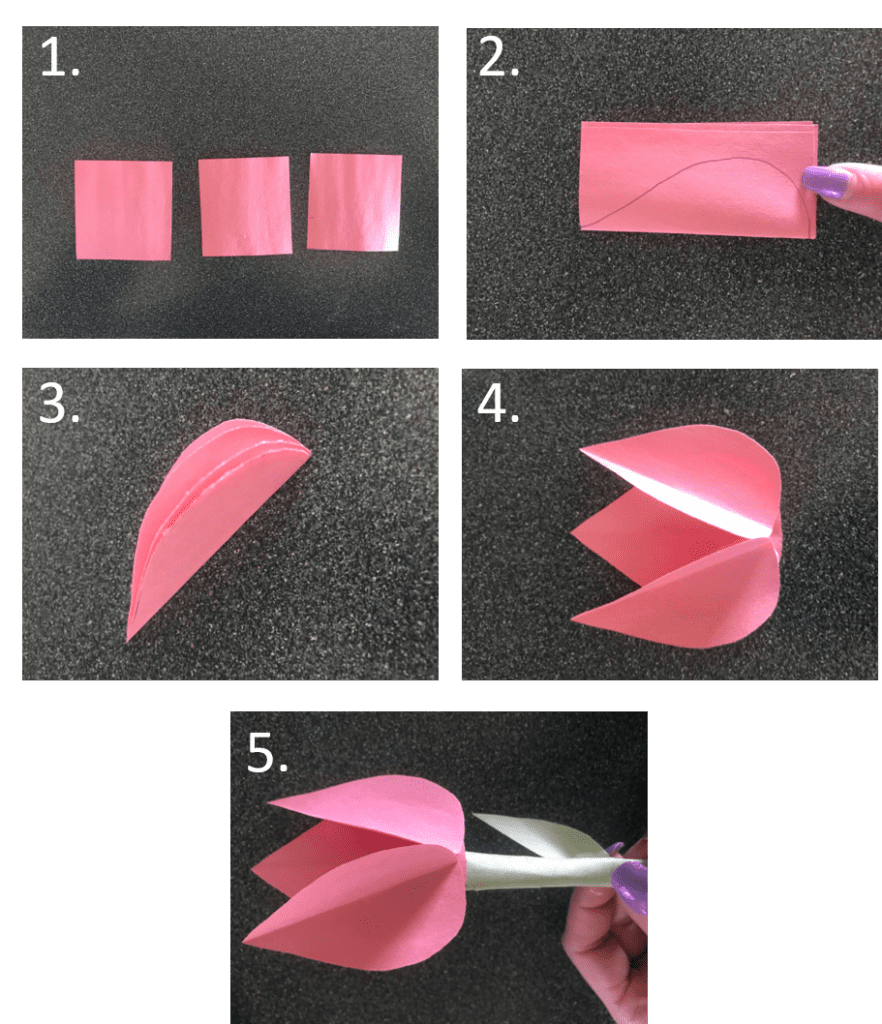

How to Make a Tulip

- Cut out three 3×3 sheets of paper. Stack the papers on top of each other and fold them in half.

- Draw a petal shape on the side of the fold.

- Cut out the petal shape using the pencil lines as a guide.

- Take one petal and glue both sides. Place the other two petals on either side of the glue. Hold down the petals gently until the glue dries.

- Create a stem (or use pipe cleaners), and glue the end of the stem to your tulip.

- Create a leaf or two and glue to your stem.

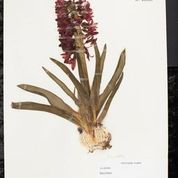

About Hyacinths

- Hyacinth has a single dense spike of fragrant flowers in shades of red, blue, white, orange, pink, violet or yellow

- Hyacinth bulbs are poisonous; they contain oxalic acid. Handling hyacinth bulbs can cause mild skin irritation. Protective gloves are recommended.

- Very fragrant, commonly used in perfume

- Though only including three species, Hyacinths have been grown in gardens and bred over the past centuries, with thousands of named varieties (known as “cultivars”)

- Wild hyacinths are native to Mediterranean and western Asia (including Israel, Lebanon, Syria, Turkey) but are widely grown around the world.

About Daffodils

- Though known by human cultures long before and grown for many centuries, Carl Linnaeus formally described and named Narcissus in his famous book Species Plantarum in 1753. The genus was also described in the Flora of North America in part by former Carnegie Museum of Natural History Curator of Botany, Frederick H. Utech, who studied many species in the Lily family, including daffodils.

- Daffodils include many species and varieties, native to the Eastern Mediterranean, but very hardy, growing very well across North America. It is not uncommon for daffodils to get snowed on and still bounce back! It has even naturalized in many areas, meaning it can survive without a gardener’s help outside of gardens.

- In Germany the wild narcissus, N. pseudonarcissus, is known as the Osterglocke or “Easter bell.” In the United Kingdom the daffodil is sometimes referred to as the Lenten lily.

About Tulips

- Tulips have a very long human history of cultivation, dating back more than a thousand years.

- Tulips were once so popular in the Netherlands that they were used as money in the 1600s!

- Seeds take 7-12 years before they’ll form a flowering bulb

- In Amsterdam, you can go on tours of whole fields and greenhouses of Tulips.

- Tulips are native to N. China / S. Europe, cultivated in Turkey by the Ottoman Empire, imported to Holland in the 1500s.

More from our Botanists

What exactly is a botanist? What types of plants do you study?

A botanist is someone who is curious about plants. That’s it! No degree required, you don’t need to be a professional botanist, but you certainly can be! Like many botanists, I am interested in many different types of plants, but in particular, study plants in our forests, especially our native spring wildflowers.

Why is this information important? Does it connect to other sciences?

The understory layer in our forests comprise many different types of species. In fact, there are far more species in the understory than the overstory! Beyond their beauty, they serve important roles in the how our ecosystem functions – from the flow of nutrients and regulating our climate to feeding bugs, birds, and animals that depend upon them. In particular, I study the impacts of climate change and introduced species in our forests. I use field experiments, observations, and our museum collections to understand the past, present, and future of the plant which we all depend. Botany connects to many areas of science, including agriculture (the food we eat!), medicine, environmental chemistry, and many more. The Section of Botany has even been consulted in legal cases and crime scene investigations.

How long have you been a botanist?

Dr. Heberling: I’ve been fascinated by plants since college, but I actually didn’t refer to myself as a “botanist” until later. Even earlier, I loved nature as a kid and grew up with a garden. Yet, I did not really discover plants as a career or calling until college. I thought I had to be a doctor to go into biology, or at least had to study animals. But at some unknown point, it clicked – plants are incredible and incredibly important! My path to becoming a museum curator was driven by my interests and only partially planned. There are many avenues to explore, many equally as fulfilling and important. And I’m fortunate to have landed where I have, in a collection of more than half a million specimens, studying the power of plants.

What is your favorite flowering plant?

Dr. Heberling: My favorite spring flowering plant: There are many! But I have a special liking to our native Trillium species. Seeing a forest full of Trillium is an experience like no other.

Sarah Williams: Hyacinth because the smell is wonderful. Forsythia because it’s the first sign for me that it’s really real Spring is here. Dutchman’s breeches because they’re pretty and look like tiny teeth.

If a child is interested in plants, what career paths could they follow and where is a good place for children to start that path?

Dr. Heberling: Get outside! That’s the best place to start. It need not be somewhere exotic. Observe. Notice what you notice. Then, start trying to identify what’s around you. Join scouting if you can, or similar groups. The best thing is to discover your passion. There are many careers that involve plants – they not only are part of the landscape, but they ARE the landscape. From agriculture to parks/recreation to many areas of conservation and scientific study – many careers directly involve plants.