Hi, my name is She-Ra and I’m an American kestrel. A scientist might call me Falco sparverius because that’s my species’ scientific name, but my friends just call me She-Ra or sometimes RaRa as a nickname! I may look small, but I am not—I am big, I am brave, and I am important.

Kestrels like me are a part of the falcon family and are closely related to bigger birds like peregrine falcons. All the other falcons are bigger than us, because we are the smallest member of the falcon family in North America, where we are also the most populous and widely distributed falcon species. This means that there are a lot of birds like me living in the wild!

Falcons like me are raptors, or birds of prey, which means that we are meat eating birds. Wild kestrels will eat all sorts of insects, small rodents, lizards, and even smaller birds! We like to grab our prey with the sharp talons on our feet. Just like humans, some of us like to eat certain type of prey over others. My favorites are mice and bugs!

I live at Carnegie Museum of Natural History in Pittsburgh, Pennsylvania, but I used to live in the wild. But I can’t live in the wild anymore: four years ago, I was hit by a car and broke my wrist, which is in the top-central part of my wing. I was taken in by the nice humans at the West Virginia Raptor Rehabilitation Center after my accident, who nursed me back to health. But even after I got better, they realized that I was never going to be able to fly well enough again to survive in the wild—even though kestrels are fierce, we’re also tiny, and sometimes bigger birds of prey try to pick on us. If I returned to the wild, I wouldn’t be able to fly away from a bigger bird! I also wouldn’t be able hover in midair, which is something really cool that kestrels can do.

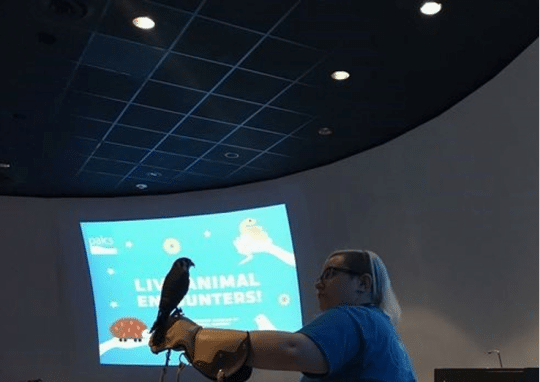

Because I couldn’t return to the wild, I needed somewhere to live, so I came to the museum, where my coworker humans take good care of me. Yes, I have coworkers because I am a bird with a job! I am an educational ambassador animal, which means I help my coworkers teach people about kestrels by appearing in Live Animal Encounters.

Coming to live at the museum took a lot of special planning, care and attention. I am protected by something called the Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918, as are all kestrels and over 1,000 other migratory bird species in North America. The museum needed to get special permits, which gave them permission to have me live here. There are even special permits for my coworkers, which grants them the great privilege of working with me!

The Migratory Bird Treaty Act of 1918 is important because it keeps birds safe. It prohibits people from killing or injuring birds or removing them from the wild. There are special cases like mine, where a bird needs to live somewhere they can be cared for by humans, but they are an exception. Something you may be surprised to hear is that the Treaty Act also protects eggs and nests, and even things like feathers! That’s right—even taking a feather from a protected migratory bird out of the wild is prohibited!

Even though kestrels are the most populous and widely spread falcon species, wild populations seem to be decreasing. No one is quite sure why there are fewer kestrels in the wild, but some possible reasons include human interference with our habitats, the use of pesticides, bigger birds preying on us more often, and road collisions (like what happened to me).

There are things you can do to help keep my wild relatives safe. One big thing is please don’t litter, especially on roads. Litter attracts delicious bugs and mice and kestrels might try to hunt them and get hit by a car. Another thing you can do is respect our space; if you see us in the wild, just leave us alone. If we seem to be sick or injured, please call the local game commission or a wildlife rehabilitation center, they have people that are trained to take care of us, much like my coworkers are trained to care for me.

If you really feel like you want to do something more to help kestrels, look into building a nest box, which will give my wild relatives somewhere safe to lay their eggs and raise their babies. If you build a nest box, you can even monitor whether any kestrels come to use it and report that information. That will help scientists learn where kestrels are living and keep track of how many of us are in the wild!

Thank you for taking the time to read my story! I hope you enjoyed learning about me and my relatives. Please check out the videos linked below. I am the star and they can teach you even more information about me!

To report injured kestrels, or other wildlife:

PA Game Commission Southwest Region: 724-238-9523

Humane Animal Rescue: 412-345-7300

Jo Tauber is the Gallery Experience Coordinator in CMNH’s Life Long Learning Department. Museum staff, volunteers, and interns are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Sensory Bin Idea: Flying animals bin

Detecting Objects with Invisible Waves: Using Radar, Sonar, and Echolocation to “See”