Pucker up! Hot lips, Palicourea elata, is a tropical tree found in the rain forests of Central and South America with bright red lips, I mean bright red bracts – modified or specialized leaves at the base of the flower. The bright red bracts evolved to attract pollinators, including hummingbirds and butterflies, and they will eventually spread open to reveal the plant’s flowers. Interestingly, this plant’s flower does not give off a scent, and relies on visual cues to attract its pollinators.

Palicourea elata is part of an important group of plants in the coffee family (Rubiaceae), and it has more to offer than what the eye can see. Species in the Palicourea and the related Psychotria genus have also been shown to have antimicrobial, anti-inflammatory, and psychedelic properties. It is also used as traditional medicine among the Amazon peoples to treat aches, arthritis, infertility, and impotency.

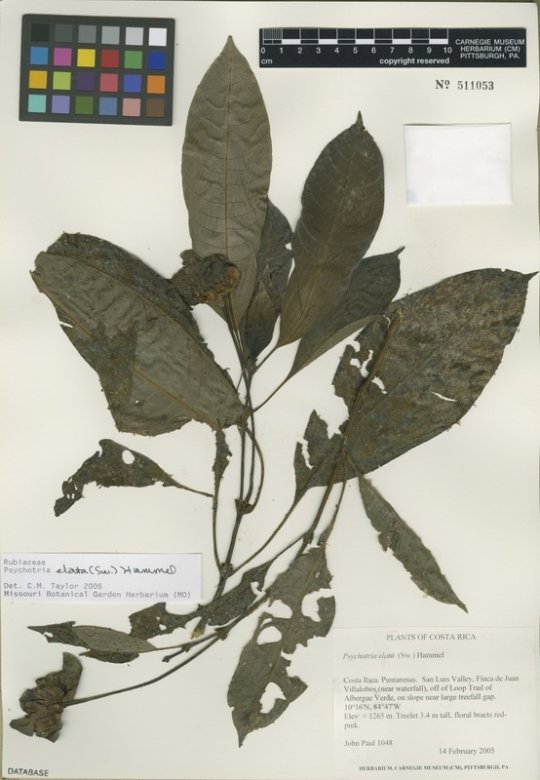

Let’s revisit a “Collected on this Day” specimen from February 14, 2005.

Though this mounted specimen doesn’t show off its striking flower, it was collected on Valentine’s Day, so that’s pretty romantic! As one of more than half a million specimens in the Carnegie Museum herbarium, this preserved plant is notable for being collected as part of the PhD research at the nearby University of Pittsburgh by John Paul, now a professor at the University of California, San Francisco.

P. elata has become endangered due to deforestation in its native range, and the International Union for Conservation of Nature, or IUCN, has reported that one-tenth of all the Psychotria species are considered threatened.

How can you help species of concern? Log your plant and animal observations into a community-based science platform, such as iNaturalist (like Hot Lips’ page). While you might not have Hot Lips in your backyard, iNaturalist can help you monitor plant and wildlife species, common or endangered. Your observations inform conservation practitioners on changes to a species range, population, behavior, phenology, etc.

Log your observations on iNaturalist the next time you’re in nature!

Heather Hulton VanTassel is Assistant Director of Science and Research at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Mason Heberling is Assistant Curator of Botany at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.

Related Content

Ask a Scientist: How do you find rare plants?