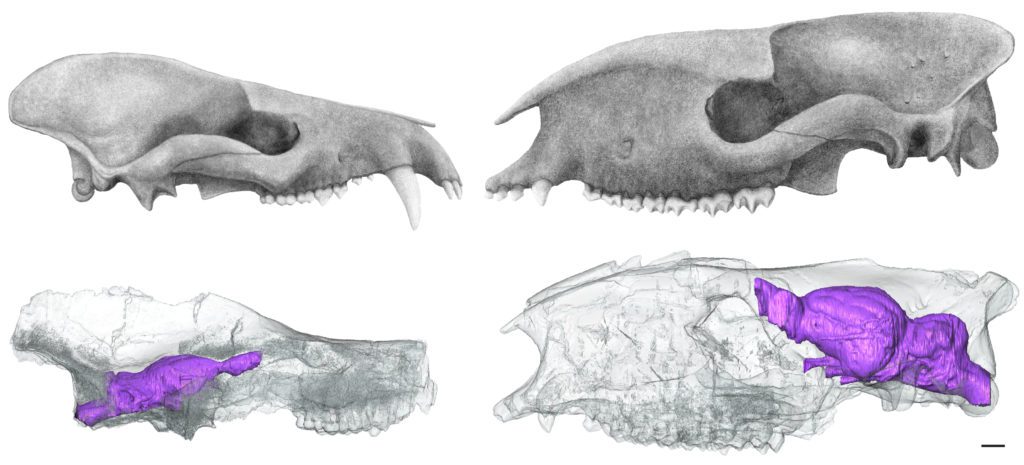

An international research team, including scientists from Carnegie Museum of Natural History (CMNH), authored a new study published this month in the prestigious journal Science finding that early placental mammals developed bigger bodies before developing proportionally bigger brains after the extinction of the dinosaurs. Modern mammals have the largest ratio of brain to body size, or encephalization, among vertebrates, and it has long been contended that this ratio emerged in the early stages of mammalian evolution. The study, “Brawn before brains in placental mammals after end-Cretaceous extinction,” finds that mammals prioritized increased body size to enhance survival in the first 10 million years following dinosaur extinction.

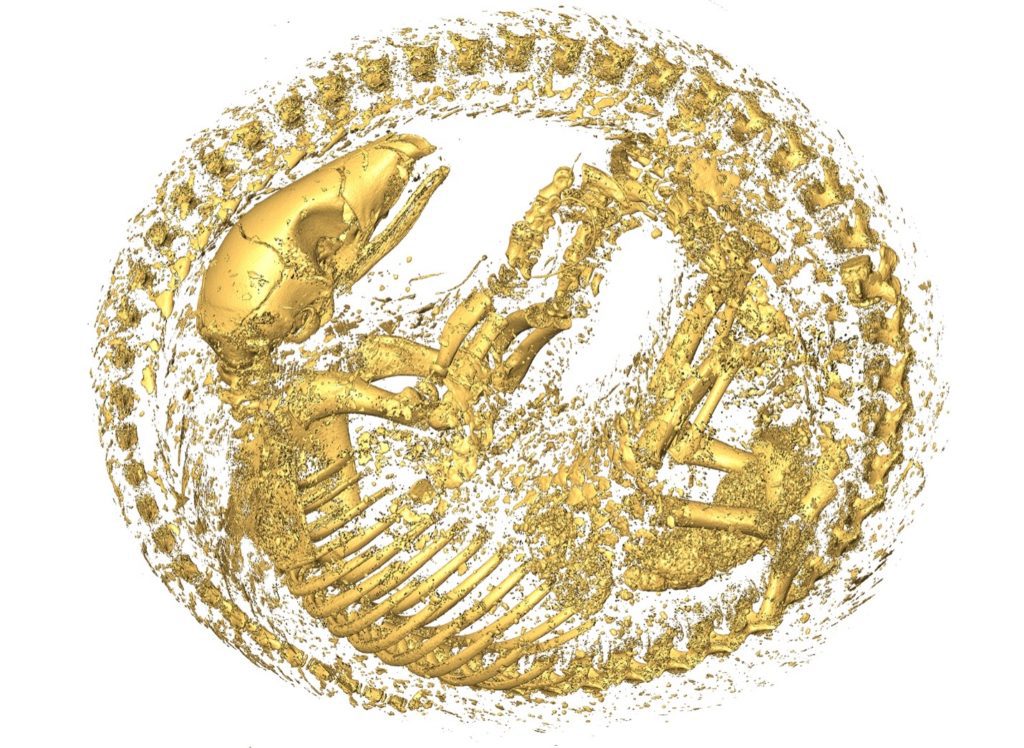

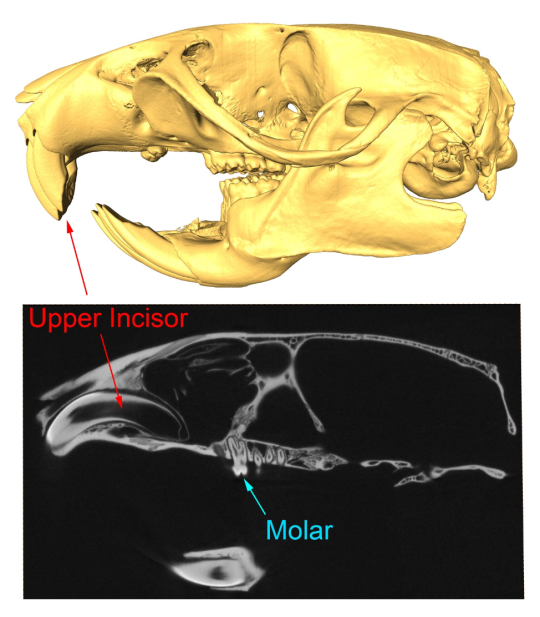

CMNH research associate Dr. Sarah Shelley and curator of mammals Dr. John Wible contributed to the study, led by Dr. Ornella C. Bertrand, postdoctoral fellow at the University of Edinburgh. The team analyzed CT scans on newly discovered fossils from the Paleocene, the epoch 10 million years after the mass extinction. The team learned that relative brain sizes of mammals initially decreased because their body sizes increased at faster rates. Their findings also suggest that mammals in this period retained advanced senses of smell, leaving the other senses—including vision—to adapt later, suggesting that size and smell were more important for survival than intelligence.

“Because modern mammals are so intelligent, many assumed that large brains enabled mammalian survival after the extinction,” said Wible. “However, it appears our modern brain is much more recent than we anticipated, arriving on the scene in the Eocene epoch, another 10 million years later. It’s very possible that large brains might have proven impediments to survival in the post-dinosaur world.”

In the Eocene, about 54.8 to 33.7 million years ago, multiple placental mammal lineages independently developed larger relative brain sizes as extinction survivors filled niches vacated by departed species. Brains continued to grow as competition surged in crowded ecosystems.

Timeline

- 66 million years ago: Cretaceous ends with mass extinction, including dinosaurs.

- 66 million-56 million years ago: Paleocene. Placental mammals evolve larger bodies, but not larger brains.

- 55 million-34 million years ago: Eocene. Most modern mammal lineages appear, including ones with larger relative brain sizes.

Shelley and Wible were involved in all aspects of the study, including CT scanning of fossils, data analysis, and writing. Shelley contributed original art to the accompanying illustrations and figures.

About Science

Science has been at the center of important scientific discovery since its founding in 1880—with seed money from Thomas Edison. Today, Science continues to publish the very best in research across the sciences, with articles that consistently rank among the most cited in the world. In the last half century alone, Science published the entire human genome for the first time, never-before seen images of the Martian surface, and the first studies tying AIDS to human immunodeficiency virus.