by Bob Jones

While on vacation, my wife and I took a morning walk on the beach to enjoy the sights and sounds of the surf while getting some exercise. The beach was mostly empty this morning and the sky was grey with the storm warnings of Hurricane Florence approaching to the south of our location in Delaware. It didn’t take long to notice a disturbing sight as we made our way on the sand. Plastic trash and lots of it. Bottles, bottle caps, beach toys, cups, straws, food containers, shoes, insoles, cigar tips and lots more. From a distance things look fine. Some clumps of seaweed on the sand. Just another day at the beach. Upon closer inspection, there are a wide variety of multi-colored bits of debris mixed throughout the tangles.

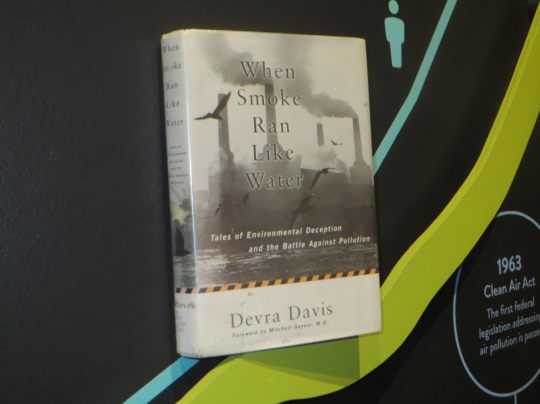

Since participating in the recent exhibition We Are Nature: Living in the Anthropocene at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History my awareness of our impact on the world that we inhabit has been raised to a new level. Of course, I’ve noticed trash on the beach in years past but the gradual increase over time is insidious in its’ nature. It creeps up on you slowly, so you hardly notice. It’s a bit like the metaphor of boiling a frog. The premise is that if a frog is put suddenly into boiling water, it will jump out, but if the frog is put in tepid water which is then brought to a boil slowly, it will not perceive the danger and will be cooked to death. I used to be more aware of avoiding stepping on jagged seashells, but now I find myself avoiding treading on the trash left on and washed up on the beach.

Don’t get me wrong, it’s not yet at an epidemic proportion at this location, but why wait until it reaches that point to act? To be honest, I couldn’t tell you if it was this bad last year or if I’m more conscious of it now. Either way, I want to share my experience and hopefully encourage others to make improvements wherever we can. After taking pictures to document the situation I felt the need to grab a trash bag and start collecting the debris for disposal. I realize that this is a big problem and it is easy to become overwhelmed. My first response is disgust and anger at the lack of care and respect that people give to the environment. My next response is, “What’s the use? Even If I bag this up it’s just sending the problem to another location.” My best response is to act with a purpose. I know that I’m just one person, but if one person can influence one other, ten others, a hundred others, to make a positive change then we have the potential to create a movement. With enough momentum, we can hold back the tide of trash and plastic that is choking our oceans and rivers.

I am old enough to remember when the air in Pittsburgh was so bad that it was impossible to see 100 feet ahead in the morning because of all the pollution released from the mills during the night. As a boy, I used to think that the buildings in downtown and Oakland were constructed with black stone because of the amount of soot built up on their surface. I was amazed when they were sandblasted in the 1980s and 90’s to reveal the brightness of the granite that lay beneath the layer of grime. The Monongahela River was thick with sludge and garbage being dumped into the water rendering it unsafe to swim in. My brother and I used to fish from the shore in the SouthSide snagging way more old tires and junk than fish. The only fish in the rivers were carp and catfish. Today, they hold tournaments to catch bass in the three rivers. That is a phenomenal improvement. In the last forty years, we have made tremendous improvements by addressing what the problem is and taking corrective action.

It is up to each one of us to not only recognize the problems that we face, but to seek and apply solutions to put things right. I was taught that when spending any time in nature I should leave things in better condition than I found them. The simple act of picking up trash and erasing any signs that I had been there is a step in the right direction. The importance of leaving the environment in good shape so the next person can enjoy the wonders of nature, as it is intended. Working together we can make a difference.

Bob Jones is the Print Shop Manager at the Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to blog about their unique experiences and knowledge gained from working at the museum.