Bats and devils are among the most popular topics associated with Hallowe’en. Of course, the research collection in the Section of Mammals has worldwide examples of bats species, but we don’t find them scary and we think about bats and their vital ecological roles all year long. Perhaps more mysterious and less well-known are the two Devil specimens stored among the wombats, kangaroos, and koalas in our collection. Even school children have heard about *our* kind of devils. Yes, the Tasmanian devil (Sarcophilus harrisii) is a marsupial – a pouched mammal, like our opossum – that is found only on the island of Tasmania, located some 140 miles off the southeast coast of Australia. Fossil evidence tells us that it once lived on the Australian mainland, but it may have been wiped out on the continent by the introduction of the Dingo, Australia’s legendary wild dog.

The Tasmanian devil is a stocky mammal with short legs, short black fur and a distinctive white throat patch. Its head is noticeably large for the size of the body. An adult male may weigh up to 20 lbs. They are nocturnal with a good sense of sight, smell, and touch. Devils are known to cover significant distances nightly, in search of carrion or prey. They can move surprisingly fast and seem to enjoy swimming. In the wild, individuals can live between five and seven years, but many die within the first year of birth. Although it is the largest living marsupial carnivore, the Tasmanian devil is predominantly a scavenger.

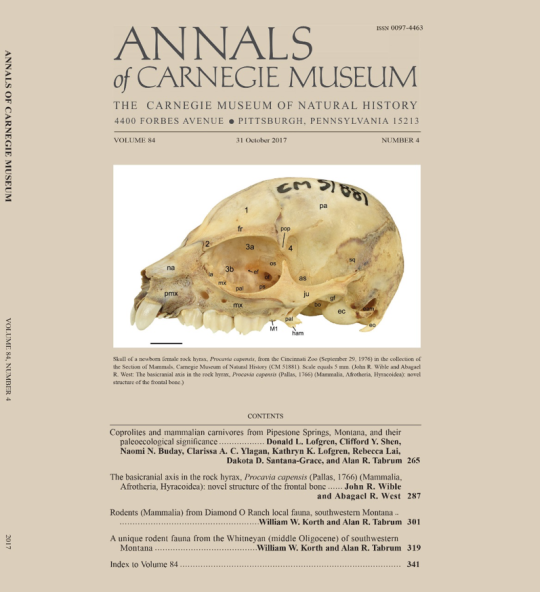

A close look at the skull shows evidence of space on the side of the head for large jaw muscles. For its size, the Tasmanian devil has the strongest bite force of any mammal – more powerful than even a hyena! With the large masseter muscles and especially large molars, it can easily crush bone. In fact, devils are such efficient carrion-eaters that they willingly consume an entire carcass, including the fur.

Although this animal gained a reputation for having a bad disposition, it is speculated that this impression was derived from the poor conditions it was kept in when first captured for observations. Since then, it sometimes has been kept humanely as a pet and been found to be much friendlier than initially reported. Tasmanian devils do not seek each other’s company except during the mating period. However, they often come together to feed on a dead animal, where vocalizations and as many as nineteen different behavioral cues are used for communication. These communal gatherings are characterized by aggression and loud sounds, described as “frequent growling” and “blood-curdling screams”!

In 1996, a sad chapter began in the existence of the Tasmanian devil. A deadly infectious cancer called devil facial tumor disease, began to spread within the population. In 2012, the Australian government transferred 30 disease-free individuals to tiny Maria Island off the coast of Tasmania, in what was called ‘island insurance’, while researchers worked on perfecting a vaccine. By 2017, the disease had led to a 90% extinction rate on Tasmania. In hopeful news, by 2019 there were indications that surviving individuals’ immune systems may be undergoing modifications to fight the disease. In early September 2020, a consortium of conservation groups released 11 Tasmanian devils to a wildlife sanctuary in the state of New South Wales, placing the Tasmanian devil on the Australian mainland for the first time in more than 3000 years. An additional 15 devils were released in early October and more releases are planned.

Currently, the Tasmanian devil is not extinct, but its recovery hangs in the balance. It would be tragic if we are left only with museum specimens and Taz, the Looney Tunes cartoon image, of this fascinating mammal.

Suzanne B. McLaren is the Collection Manager in the Section of Mammals at Carnegie Museum of Natural History. Museum employees are encouraged to share their unique experiences from working at the museum.